From royalty to retrofit; sustaining the culture and condition of a historical rural village

| This article is the elongated version of of the article Clovelly, which originally appeared as ‘Sustaining a rural village’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 178, published in December 2023. |

[edit] Introduction and early history of Clovelly

For those have not heard of Clovelly, it is a historic fishing village directly on the North coast of Devon, famous for its steep cobbled stone high street, spectacular views, and special story steeped in English history. A more detailed history of the village can be found on the visitor information on the Clovelly website.

Clovelly doomsday CC-BY-SA licence credit Prof John Palmer, George Slater and opendomesday.org

The area around the village has been inhabited since the Iron Age, William the Conquer featured ‘Clovelie’ in the Doomsday book of 1085, and it was gifted by him to his wife Matilda of Flanders, who was the first crowned queen of England. On her death and on through the next 200 years the village and land passed through different hands, until during the 14th century reign of Richard II, when indication is that the Manor of Clovelly, an agricultural parish was bought by the judge Sir John Cary. His younger brother Sir William Cary is said to have built the original stone breakwater, which created a harbour and transformed the site into a much-needed fishing village and stopping point of the North side of the Devon coast.

[edit] Carriageways and creativity

The family kept and resided in the village for eleven generations, until last Cary of Clovelly, Elizabeth Cary died and her widower, Robert Barbour, sold the village in 1738 to Zachary Hamlyn, who was born in a neighbouring village and acquired his fortune as lawyer in Lincolns Inn. After passing, his to his nephew, and then on to a next generation, who used inheritance to fund improvements, including the construction of carriageways, completed in the early 1800’s. Shortly after in 1811 Joseph Mallord William Turner sketched and then painted a scene from a viewpoint up the coast with Clovelly in the background, which hangs in the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin.

Joseph Mallord William Turner. Clovelly Harbour 1811_Sketch as a source for the watercolour Clovelly Bay of about 1822 (National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin) Tate.org. image William_Turner_-_Clovelly,_North_Devon_-_B1977.14.6302_-_Yale_Center_for_British_Art CC0 1

.

In 1855 Charles Kingsley, who lived in Clovelly as a young man, wrote the historical novel Westward Ho! Set in and around the village. Whilst Clovelly is also mentioned in the Christmas issue of All the Year Round from 1860 written by Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins. Image 6

Title_Page_Charles_Kingsley_Westward_Ho!_(1855) CC.png and A message from the sea: The extra Christmas number of All the year round by Dickens, Charles, 1812-1870 Publication date 1860 Publisher [London : s.n. Collection cdl; americana digitizing sponsor MSN Contributor University of California Libraries Languag]

[edit] Standards and Culture

A few years after a horrendous storm destroyed boats and killed many fishermen, the village passed to possibly one of its most significant inheritors, Christine Hamlyn Fane (Great grand Aunt of the current owners). She married Frederick Gosling and persuaded him to change his name to Hamlyn, because of their long association; and to devote his banking fortune to the restoration of the buildings of the estate. The long process, still marked by their initials and dates on each house, brought properties back from disrepair and raised living standards for the, some 500 tenants, up to expectations of the Victorian age. An era that in many ways spawned the relatively new industry of tourism, which saw the village of Clovelly gradually become a destination for short breaks. Perhaps increasingly aware of the possibilities of tourism, in 1932 Christine Hamlyn commissioned the artist Rex Whistler, to paint her portrait (Rex John Whistler (British, 1905–1944) Title: Portrait of Mrs. Hamlyn, Clovelly Court, Devon) but also to design a toile de jouy fabric (a popular fashion at the time) which was known as the Clovelly pattern. The pattern was adapted by Wedgwood for use in a range of ceramic tea-wares, which again helped to raise the profile of the small village with a cultural draw and facilitated a form of income.

Ref 4 Rex John Whistler (British, 1905–1944) Title: Portrait of Mrs. Hamlyn, Clovelly Court, Devon

[edit] Tourism and financing

Some 50 years later the village passed down to another, the current and equally significant inheritor, the Hon John Rous. He made a decisive if some-what risky move, perhaps aided by his training, but also following the pattern that started during the Victorian period. He built a modern visitors centre, out of sight of the village and introduced an entrance fee for guests. This was a way to generate the much-needed income needed to maintain upkeep and eventually improve the historical buildings, whilst importantly keeping the existing community of tenants in place, whilst carefully introducing new community members. The visitor centre and the entrance fees were certainly not appreciated by all, and for a time in the world of public reviews the village suffered some bad reviews during what could be considered as a teething period. However, now, nearly two decades later, one might say that the village (rather than just Mr Rous himself) is seeing the fruits of his labour. As part of this article, I was lucky enough to speak to Mr Rous about the village, about its long history of which he is an important part but also about its recent refurbishment initiative, technical issues around materials, technology, performance, aesthetics, and sustainability goals, both financially speaking as well environmentally

“There was a difficult period I think for people owning rural properties, when rental income was restricted by regulation, that made it very difficult to maintain the properties and the buildings were rather run down again because of this. I thought when I first got involved one could tweak the tourism business and then imbed the renovation but then I realized after, that we needed to do something much more radical. We decided that at the very least we had to protect our tourism income by investing in better facilities for our day visitors, with great support from architects, builders and advisors a visitor centre was built. This generated funds to spend on the facilities and also cottage renovations, which in turn benefitted the rental offer to the community.”

[edit] Respect and protect

Historically the financing for the previous major refurbishment works in the 1800’s and 1900’s was achieved through the wealth of an individual benefactor with family money. Today the model that Mr Rous has begun to achieve has at least some possibility to be self-sustaining, with the possibility to keep the village alive both as a tourist destination but also increasingly popular as a place to live. Clovelly, steeped in history is a reminder of times gone, improving the visitor experience as well as the quality of tenant life, keeping in mind the broader view for longevity of the physical as well as social fabric of the village.

’On the tourist side, we have a respect for our history, and we really do need to know what it was like living in a village like this 100 years ago, which would have been very, very different, lucky if once a week you had a tub in front of the fire filled up with hot water, and that’s what we show at the Fisherman’s’ cottage. But yes, the village is very much alive and today you wouldn’t get many volunteers for a hot tub bath. Ever since taking the village on I was very much aware of peoples heating bills and the enormous chimneys up which a lot of hot air left but had minimum benefit for the properties. So, we have now for some thirty years been installing lined flue-based system, with interlocking insulated pumice blocks6which has benefit of reducing fire risk (something I have always been very anxious about) but also mitigating heating bills, alongside our ongoing repairs and maintenance before we were able to move onto other things’

Ref 6 https://www.schiedel.com/uk/products/pumice-system-chimneys/isokern-dm/

[edit] Contemporary culture and context

The village is in many ways exists as a contradiction, for whilst being a display of historical buildings, an open-air museum piece viewed by paying visitors, at the same time it continues to be a thriving, vibrant and very much living village with a very strong community of around 300 residents. Mr Rous didn’t disagree when I indicated he knows the tenants and normally speaks to them personally before anyone new moves in, which shows a particular and engaged culture of rental, perhaps often missing. So much so that in 2022 Clovelly Estate Company won the award for National Landlord of the Year at the Energy Efficiency Awards in 20227. It is not an easy task, to maintain the simple beauty off the village, equip it as tourist destination, provide for contemporary rental and be part of the small community. But one might say however that the contemporary culture of Clovelly is today as strong it ever has been, with its popularity as a place to live only increasing and resident filmmakers, artists, musicians, craftspeople continuing the cultural life of an extra ordinary village. So much so that quite recently this Devon village was named most stylish place to live8.

Ref 7 Insulating a village. By Mukti Mitchel. February 22nd, 2022. https://carbonsavvy.uk/uncategorized/insulating-a-village/

https://www.devonlive.com/news/devon-news/idlyic-devon-village-named-most-8536287

Ref 8 Idyllic Devon village named most stylish place to live. By Elliot Ball Reporter. June 2023. https://www.devonlive.com/news/devon-news/idlyic-devon-village-named-most-8536287

image 10 Return to Clovelly Listed village retrofitted for the future; Mitchell and Dickinson image

[edit] Improving the fabric and certifications

In 2016 the Clovelly estate commissioned listed property insulation experts Mitchell & Dickinson to start a major refurbishment project on the village, with similarities to the extensive work carried out by his Great grand Aunt in the 1900’s. This most recent refurbishment project was in many ways ahead of the curve by around 5 years, because by the time of the most recent energy crisis, most of the buildings were by then complete. I asked Mr Rous how this came about and how much was a legislative push with increasing pressure from Energy Performance requirements and how much was a choice on the part of himself or the estate?”

“So, there was an element of legislative push on the Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) side but as I said since becoming more involved, I have been very aware of heating costs in a village like this That has been a driver for a long while, along with, well, the longer story of building up enough capital to be able pay for, what were likely to be major works. In terms of practicality though and, something I have beefed about in the past is that the EPC gave us something like two or three points for all the careful work we did to improve the historic fabric, whereas if we had just installed high heat retention radiators, we would have got more like fifteen points. Which to me really seems bonkers, it does not make sense because in practical terms, having installed some such radiators we found they were very expensive for tenants to maintain, and some were coming back and asking for them to be removed. So, in a way seeking a higher EPC would have pushed us more towards a technology fix rather than the deeper, and in my opinion, more carefully thought through work that we actually did.”

[edit] Project phases and technological choices

One of the most difficult elements perhaps of long-term efficiency refurbishment programmes including fabric upgrades are the technological choices. Microgeneration technology is continuously developing, efficiencies improving, market prices dropping and funding mechanisms changing. As well as question marks around the various government energy efficiency programmes, there has also often been criticism of a disconnect between fabric improvement and technology programmes. From Clear Skies programme, to the Green Homes Grant, Clean Heat Grant, and then the now cancelled Renewable Heat Incentive, finally we arrive at the Governments current Boiler Upgrade Scheme (BUS) 9.

The BUS has recently been increased to 7.5k towards the capital cost of approved microgeneration equipment on the basis of an EPC. Since the early days of the Energy Technology Product List, (for the Enhanced Capital Allowances)10, to the Microgeneration Certification Scheme (MCS) product list 11 ,from which the BUS Product Eligibility List (PEL), published by Ofgem is arrived at. There are a number of things to note, here, firstly the list now has an impressive, almost 3000 products on it from air/water and ground-source heat pumps to biomass systems, and the scheme has a nod to fabric improvements by requiring any insulation improvement recommended made by the EPC to be carried out first. Whilst the Great British Insulation scheme (GBIS) 12 is effectively separate, and EPCs have their own criticisms, the recognition of impact of the building as a whole with the technology is a step in the right direction. For whilst there good evidence for example of the success of heat pumps in historic buildings 13, there can be a danger in assuming a one size fits all by simply swap one tech for another, which is simplifying the story. There is a grey area though here perhaps a grey area here in terms of levels of fabric improvements, discussed later.

A local heating engineer gave a good description of the issue, clarifying this relationship between practical performance, fabric performance and the efficiency of systems, using heat pumps as a case in point.

“In terms of heat pumps the flow temperature set out by the Microgeneration Certification Scheme (MCS)is 55 degrees C, and their minimum seasonal co-efficient of production (SCOP) is around 2.9. However, in terms of heat pumps, running below 50c is more efficient, whilst a 45c flow temp is ideal, which can help achieve a SCOP of up to 4. Compared to gas boilers which run nearer degrees, all these figures seem low for this to work though the heat loss of the building needs to be at a reasonable level, which is where the fabric performance, insulation and air tightness starts to be key. It’s important to try and reduce the estimated heat loss for older buildings, which might be around 65-85 W/m2 to less. In comparison newer buildings (post 2006) might be around 20-40 W/m2, and Passivhaus at nearer 2-10 W/m2. However, these details are often missing in a tech solution that says heat pumps will fix it, their efficiency can in effect vary by a factor of 2!’

In terms of project phases in a programme such as for example Clovelly, timing is often everything, but by focussing on the fabric improvements the estate has placed the houses in a stronger position for whichever tech suits from a practicality, efficiency, or economic standpoint. To swap in new technology for perfectly working systems also doesn’t really make sense if we start to incorporate such things as embodied carbon of these new pieces of kit, but when replacement cycles come up that is perhaps the time to look again.

ref 9 https://www.gov.uk/apply-boiler-upgrade-scheme

ref 10 https://www.gov.uk/guidance/energy-technology-list

ref 11 https://mcscertified.com

ref 12 https://www.gov.uk/apply-great-british-insulation-scheme

ref 13 Heat Pumps in Historic Buildings Air Source Heat Pump Case Studies – Small-scale Buildings. Historic England.

[edit] Microgeneration and materials

As we discussed the ideas behind microgeneration of which heat pumps is the technology attracting most attention, other perhaps more fitting technologies such as chip, pellet and log biomass systems can also attract capital grant funding and appear on the BUS list. Pondering the wider issues around microgeneration in such a sensitive location it seemed also logical to bring up yet another technology, which has come on leaps and bounds over the past few years. Photovoltaics, and in particular solar slates, which are now being produced not so many miles away over the water in Wales. GB Sol 14amongst other products, manufactures a solar slate product that to my untrained eye looked the nearest I have seen to actual slate, I wondered how this kind of product might go down in a place like Clovelly, where the roof scape is so important.

image 11 Roofscape Clovelly landscape by D.Rigamonti

In the same way as the programme of insulating the chimneys, the issue of phasing or cycles of refurbishment, comes in to play as well as cost. The estate has been gradually replacing, repairing, and refurbishing the roofs of the cottages, over recent years, so essentially the idea replacing newly refurbished slates roofs with the solar equivalent just wouldn’t really make logical or financial sense, but it did bring up an interesting element about materiality. The roof scape of the village is mainly slate and seen as one walks from the visitor’s centre down the cobble stones into the village, though there are one or two thatch roofs in the upper village that are thatch. I discovered the aesthetic of the slate to be something Mr Rous feels quite passionate about, and perhaps ot is this depth of material understanding that gives the village its quality. If it were appropriate to look at solar slate and to my eye at least they look ok but might changing such a predominant traditional material slowly chip away at the deeper materiality and feeling of a place, somehow where heritage and history is embedded within the materials.

image 12 Chimney cap details landscape by D.Rigamonti

“Well yes we do use a local slate, in preference to the significantly cheaper but often more brittle alternatives from Brazil or China. I really do have an emotional attachment to the Delabole slate15, the quality of the material its, gradations in color and we have found it to be long lasting and hard wearing, as we repair and replace slates. You can also find very good quality second-hand slates if the quarries order books are full. Traditionally in the village there were no wind cowls as such but what they used to have, which I must say is something I am fond of and I try to protect if I can, is simple two stacked Delabole slates. They cut a fillet out of one of the slates and angle them together to support one another and it looks really rather charming as a finish to our chimney works.”.

Ref 14 https://www.gb-sol.co.uk/products/pvslates/default.htm

Ref 15 http://www.delaboleslate.co.uk/

Whilst we didn’t discuss microgeneration using wind power at the individual property level, and perhaps if wind cowls were a prominent feature of the roofscape, as historical was the case in the south coast of the UK, maybe there might be further room for debate. However, without ruling it out, we did more readily discuss the possibility of larger village scale wind power when discussing the village in the concluding section.

[edit] A culture of fuel

Having invested heavily insulating and fireproofing the longstanding listed chimneys one can understand the hesitation is switching to the electrification solution of heat pumps. Although open to the idea, there are also reservations in terms of access, the steep incline of the village and the need for topping up, the lower grade heat. In the mean-time biomass seems to fit the culture of the village more readily, though again with many working, but not MCS recognised biomass burners the idea of replacing these also seems essentially wasteful. The thought of walking through this historic village, off-season without the smell of wood burners (and yes in some cases currently smokeless coal), it would feel like an element is missing in this historic scene. I mean can solid fuel or biomass be considered as culturally significant in such an environment, or indeed anywhere? If perhaps all cottages were able to get to the level and example of the buildings of the estate itself, Clovelly manor and use only locally grown firewood that might be a more appropriate change than to electricity, and maybe there are other solutions that look again at efficiency rather than replacement.

One British manufacturer, Recoheat16 would say it has at least one, cost effective answer to add to the mix in via their innovative pumped air heat recovery systems for wood burning stoves17. The system, retailing at just a few hundred pounds couples an air pump to a heat-recovery element set in the bottom of a stove flue, forcing a jet of heated air from the front of the flue just above the stove. This then entrains and circulates the heat rising from the stove to increase the volume and distribution of warmth around the room. The positive pressure this creates in the room can then be distributed out into the rest of the house to create convection flows of warm air that will circulate to a far greater extent than can be produced by the stove on its own. Indicatively in some cases increasing stove output by some 1kw for the same fuel input (if we think in the SCOP terms as with the heat pumps).

image 13 Before and after comparison www.youtube.com Recoheat https://www.youtube.com/@Recoheat

The manufacturer, who has also tested its product using CFD 18, describes the secondary effect of more even heat distribution, which is to helps to avoid hot pockets of air in cold areas, this reducing condensation issues in older properties. This touches on another issue common in older houses, particularly those being occupied to contemporary standards, which is moisture build up and ventilation. Might this kind of efficiency improvement be enough to keep the wood fires burning? It certainly feels like a more natural step change improvement for a place like this, though either way all of these kinds of adjustments benefit from fabric improvement, whihch is something the estate understands well.

Hyper links / Refs

Ref 16 https://www.recoheat.co.uk

Ref 17 https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/Pumped_air_heat_recovery_systems_for_stoves

Ref 18 https://www.youtube.com/@Recoheat

image 14 Clovelly sledges for materials by D.Rigamonti access granted courtesy of Clovelly estate

[edit] Restorative upgrades

The challenge for listed property experts Mitchell & Dickinson19 was huge, to bring 107 17th-century buildings up to modern insulation standards and reduce energy bills while preserving their character and beauty, with access via a steep cobbled street. The solution lay in part with a new system developed by the company and saw the grade two listed buildings upgraded with one vacant building used as a workshop and despite the challenges of accessibility for materials and labour.

“One of our constraints was from the conservation side we couldn’t go for external insulative cladding, secondly the rooms are small so internal cladding would often be inappropriate. We accepted these as constraints that we had to live with, whilst the lining and insulation of the chimneys had been implemented from the early 1990’s. The emphasis was on the secondary glazing because it is so unobtrusive that it is hard to notice from the inside and most definitely not from the outside. They stripped off layers and layers of paint, to refurbish the windows, fitted heat stops around the window to seal it well and then at last fitted the secondary glazing, as such refining the system as it was to achieve better performance”

“The work involved fitting sheep’s wool loft insulation, bespoke draughtproofing and the unique secondary glazing system (using plexiglass and magnetic tape) called CosyGlazing20. This allowed the installation of almost invisible secondary glazing onto existing windows, and quietly revolutionised the conservation of timber and glass windows in listed buildings. The team were clear also of other hurdles and approached the project with early adopters who help progress the work by word of mouth and recommendation to others who were less convinced.” 19.

This is something one feels sure that Christine Hamlyn would have been highly approving of.

Ref 19 Return to Clovelly Listed village retrofitted for the future; extract Mitchell and Dickinson.

Ref 20 https://mitchellanddickinson.co.uk/services/secondary-glazing/

Ref 21 https://mitchellanddickinson.co.uk/landlords-and-estates/clovelly-case-study/

image 15 Example refurbished Clovelly home by D.Rigamonti access granted courtesy of Clovelly estate.

[edit] Estimating performance

The village is in some ways a good example of how one size perhaps doesn’t fit all, indeed none of the cottages are the same. In such a context, with a mix of solutions from Rayburns, wood burners with heat leak radiators and sometimes hot full water systems as well as some with those point scoring storage heaters, perhaps one or two heat pumps and more likely a modern biomass, might be interesting to compare. Rightly or wrongly the preference remains with solid fuel solutions, and although not perhaps the easiest option on a day-to-day basis, in a historic place where shopping is via a sledge or donkey, it does feel appropriate. I mean you choose to live in Clovelly for other reasons than convenience for sure. The principle though that does tie the properties together in terms of performance remains the same (as it should do even with heat pumps) that is efficiency comes first, to get as much as possible from whatever the heat source is, by firstly improving the fabric performance.

“In many cases the improvements, such as to the windows are simply almost immediately noticeable, whilst others not so. The wall build-up that we have is still something that, well doesn’t feel as accurate it might be because of the natural materials and in some cases the thickness. It is though true that we as yet haven’t carried out more exacting thermal performance tests or air tightness measurements, but it is something we would be keen to do now the project is complete and installations have settled’

Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) have for quite some time been criticised, for their ability to be overarching and accurate, in 2019 a study Impacts of inaccurate area measurement on EPC rating 22suggested up to 2.5 million EPCs were inaccurate because of floor area assumptions, for example. More recently the Sunday Times in February 2023 23 reported staggeringly inaccuracies with the certification scheme, referencing research by CarbonLaces24, which indicted overestimation in energy use by up to 344%. The debate on the value of EPCs continues, whilst many agree the scheme is not perfect there is sometimes a miss interpretation of their purpose, as Andrews Sissons of social innovation agency Nesta pointed out this year “EPCs are not meant to measure actual energy use, but how efficiently a home uses energy. These aren’t the same thing. Many inefficient homes, for example, are under-heated because their occupants can’t afford enough energy" 25.

Ref 22 Impacts of inaccurate area measurement on EPC rating. Nirushika Nagarajah, City University of London and Joseph James Davis, University of Kent https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/6095a610a4763f422bdafe21/60f946d24b08cd0545e06743_White-Paper_Impacts-of-Inaccurate-Area-Measurement-on-EPC-Grades-min.pdf

Ref 23 Why misleading EPC ratings are a national scandal? https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/why-misleading-epc-ratings-are-a-national-scandal-ztc5ss2b0

Ref 24 https://carbonlaces.com/blog

Ref 25 https://www.nesta.org.uk

image 16 Clovelly bay landscape by D.Rigamonti

[edit] Default values

A review of EPCs has though for-sometime been in the pipeline, from a government consultation launched in 2018, an EPC action plan in 2020 26, to the required modelling updates in June 2022, SBEM for non-domestic version 6.1b 27 and SAP10.2 (Standard Assessment Procedure) for dwellings. However, the Reduced Data SAP (RdSAP) which is used to assess energy performance in existing dwellings (and also feeds into EC4 and the GBIS), is not due to be updated to RdSAP10.2 until March 2024 28. So here perhaps lies at least some clues for existing buildings such as those in Clovelly.

The paper “The over-prediction of energy use by EPCs in Great Britain: A comparison of EPC-modelled and metered primary energy use intensity” 29 published in March 2023, showed that whilst EPC in bands A-B were relatively accurate, the picture lower down the scale is somewhat different with bands F-G over estimating energy consumption by up to almost 50%. This work “Unlike previous research, we show that the difference persists in homes matching the EPC-model assumptions regarding occupancy, thermostat set-point and whole- home heating; suggesting that occupant behaviour is unlikely to fully explain the discrepancy.”

Perhaps one of the likely reasons for these discrepancies at these lower levels is the role of default values for buildings prior to 1978 or 1900, something that has also previously been highlighted in the case of solid walls. The paper ‘Solid-wall U-values: heat Flux measurements compared with standard assumptions” 30 back in 2015 showed a possible over estimation of 16% in the heating demand of a solid walled dwellings that used default U values of around 2.1 -2.6 because the walls in reality performed better.

The more recent paper “Determining realistic U-values to substitute default U-values in EPC database to make more representative; a case-study in Ireland” 31 in its own words concluded “Inherent in all EPC methodologies are trade-offs between reproducibility, accuracy, assessor expertise and costs. During an assessment, where accurate building data acquisition would be excessively invasive or costly, nationally specified default values are used. Default values are necessarily pessimistic to; avoid a better-than-merited rating, enable homeowners to know the advantage of energetic refurbishment, encourage homeowners to record upgrades informing EPCs, and propel assessors to seek-out information to provide an accurate rating.” However, in reviewing default U-value use across Europe and the UK before focusing on Ireland, it found ‘1 in 3 entries… characterised on default U-values in 2020, leading to the dataset presenting an overly pessimistic view of the stock, thus lacking validity.”

Ref 27 https://www.uk-ncm.org.uk/filelibrary/SBEM_Technical_Manual_v6.1.b_29Apr22.pdf

Ref 29 The over-prediction of energy use by EPCs in Great Britain: A comparison of EPC-modelled and metered primary energy use intensity. Energy and Buildings Volume 288, 1 June 2023, 113024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378778823002542

Ref 30 Francis G. N. Li, A.Z.P. Smith, Phillip Biddulph, Ian G. Hamilton, Robert Lowe, Anna Mavrogianni, Eleni Oikonomou, Rokia Raslan, Samuel Stamp, Andrew Stone, A.J. Summerfield, David Veitch, Virginia Gori & Tadj Oreszczyn (2015) Solid-wall U-values: heat flux measurements compared with standard assumptions, Building Research & Information, 43:2, 238-252, DOI: 10.1080/09613218.2014.967977

Ref 31 Determining realistic U-values to substitute default U-values in EPC database to make more representative; a case-study in Ireland. Energy and Buildings. Volume 274, 1 November 2022, 112358. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378778822005291

image 17 Clovelly broadband and homes by D.Rigamonti

[edit] Assessing performance

Now the perhaps slightly grey area when considering historic and listed buildings, whilst some studies show lower EPC performing buildings (in which listed buildings might likely fall) may be over pessimistic in performance, the recommendations may well include U-value improvements. Whilst this is right, it isn’t unclear at this stage if levels of improvements or improvements elsewhere might be accepted also in the case of buildngs with historic and listed facades and windows. This now becomes relevant if those buildings seek BUS funding, because (in many ways rightly) the scheme requires recommendations of the EPC to be carried out, prior to eligibility, which perhaps puts older buildings with issues such as Clovelly at a disadvantage.

So where does that leave clients and buildings such as those in Clovelly? One thing that has become clearer over the past 10 or so years throughout the industry is the value of Post Occupancy Evaluations also called Building Performance Evaluations. In non-domestic projects POEs or BPEs remain an important tool and increasingly included in project scoping, but less so in domestic buildings. It is also in the non-domestic sector, particularly public buildings have also been familiar with Display Energy Certificates (DECs) since 2009, which importantly unlike EPCs are based on actual energy use data for the buildings.

However, a British Standard for Building Performance was first suggested by the Retrofit Standards Task Group, a body set up as the standardization work-stream of the ‘Each Home Counts’ government-commissioned review of consumer advice, protection, standards and enforcement in relation to UK homes energy efficiency and renewable energy measures. That standard released in early 2022 and named BS 40101:2022

Building performance evaluation of occupied and operational buildings (using data gathered from tests, measurements, observation, and user experience). Specification 32 is a good starting point.

Whilst there are no requirements for air tightness testing in existing buildings, particularly listed buildings, maybe there is an increasing sense in doing so, perhaps along with thermal imaging and more detailed envelope assessments than defaults. With alternative methods such as pulse air tightness testing the ease, as well as the price of carrying out tests has gradually been coming down. What is clear as a minimum though is the benefit of reading meters and measuring use of energy before and after any intervention. The proof is often in the pudding as one might say, irrespective of the EPC rating…

“One early adopter reported her heating costs were reduced from £2,400 per annum to £1,200. She said: “Not only am I saving 50 per cent of my fuel bills, but my home is far warmer. I used to run the Rayburn on ‘roast’ all winter, now it runs on ‘simmer’. I used to have an electric heater on for three hours every evening in my baby’s bedroom yet last winter I didn’t use it once. Anyone would be mad not to have their home insulated” 33.

It is though, also worth mentioning another approach, which in many ways covers more detailed pre assessments of an envelope, certainly way beyond default values, to include more rigorously thermal bridges, as well as compulsory air testing. The EnerPHit 34 standard is for existing buildings and developed by the Passivhaus institute. Whilst Passivhaus remains one of the most stringent assessment methods, their refurbishment standard, although still a challenge has reduced targets for example. Whilst some may not be willing to go the whole way with the standard, it is perhaps worth noting, in some ways perhaps more than the standard itself, this more stringent approach to assessment of the building envelope.

Ref 33 Return to Clovelly Listed village retrofitted for the future; extract Mitchell and Dickinson.

Ref 34 https://passipedia.org/certification/enerphit

image 18 Clovelly street view by Dan Rigamonti

[edit] Retention, recovery and moisture

So far, the focus has been on how fabric performance, effects heat retention, in simple terms by effectively sealing the box of the building, as well as the technology and fuel used to heat that box, so to speak. However, as briefly touched upon earlier, how that box is enclosed also impacts performance. Where hygroscopic materials, often common in older dwellings, such as timber or lime plaster can have significant impacts on temperature in the spaces, acting as buffers to moisture levels, which in turn impact comfort. How thermally massive materials such as stone, slow transfer, taking time to warm up but also help these buildings stay cool in the summer, all forms of heat (or in the case of summer months coolth) retention.

The goal of maintaining a consistent envelope helps avoid cold spots that can cause condensation and eventually mould, something that can be exacerbated by the contemporary living standards, from moisture producing cleaning and washing. Whilst hygroscopic materials can go some way to help buffer moisture levels internally, more-often-than-not the levels of moisture, historically were helped by filtration or ventilation through the envelope of the building. With the discussed improvements to that envelope, these forms of uncontrolled ventilation are hopefully reduced, which in turn can exacerbate moisture issues thus increasing the importance of controlled ventilation and the simple regular opening of windows.

“My mantra is that we have got to keep the house continuously heated on a low heat basis and if you do that you can help to minimise the damp problem. You also need to be particularly careful about ventilation, particularly as we improve the draft proofing of the cottages. We do encourage our tenants to ventilate the cottage for an hour a day, and supply tenants with guidance to this effect, but it’s not something you can enforce.”

Other cost-effective approaches that the estate have looked at can also help with moisture issues such as Positive Input ventilation (PIV) where a small fan draws tempered air from an attic space and pushes it into the occupied space. This encourages the dwelling into a positive pressure scenario bringing in drier tempered air via the fan whilst pushing or exfiltrating moist air out through the fabric, reducing cold drafts (or infiltration caused by negative pressure) in the process. Whilst PIV brings tempered air into the building, heat is still effectively lost with the air replacement, heat exchangers try to minimise this.

[edit] Recovery and reuse

The issue here being, if we keep our efficiency goggles on is that when we open the windows, in the winter we are replacing stale moist air with fresh air, importantly impacting the last element of the heat loss calculation beyond fabric. That we are losing the heat we have so carefully generated. So really what we want is to get rid of the moisture, and the carbon dioxide in our internal air from breathing, by bringing in fresh air but keeping the heat inside our envelope, without losing the opportunity to open windows if we need.

There are many types of different heat exchangers but in general re-couperative heat exchangers are increasingly used in single sided heat exchange extractors used to replace traditional bathroom extractor fans. These in general (but not exclusively) work by introducing a heat battery which absorbs warmth as stale air passes and releases it to fresh incoming cooler air, they work but are generally considered not as effective as regenerative heat exchange. A typical regenerative heat exchanger of the counterflow type is used in heat recover systems often flat plate heat exchangers, these exchange heat between the two air flows more directly and are thus often more efficient and often used in MVHR systems.

There are many DIY versions of home-made heat exchangers to be found online, using small computer fans for intake and extract air, many require large plenum boxes to create larger surface areas for more effective exchange. Some single singed versions do also exist with effectively two tubes inside one another running a length of a space drawing warm air in one tube on one side and cold air the other, passing by one another for the length of the run some heat can be exchanged. How effective these solutions are is really a guess and for now no tested commercial equivalents stand out. However single sided ventilation heat recovery units are available from companies such as vent axia 35, though do not appear as part of the current government grant schemes.

Ful Mechanical Ventilation Heat Recovery (MVHR) systems however often fulfil the brief probably more fully with some systems stating they recover up to 90% of the heat system and equally valuable to know is the added advantages of removing moisture as well as filtered particles. Whilst recommendations vary dramatically, the higher end recommendation is MVHR should only be used in dwellings with 5 m3/h m2 or less at 50Pa, whilst enerPHit states less that 1 AC/hr@50pa is deemed satisfactory, which indicatively might be considered as less half this at under 2 m3/h.m2@50pa. So this is where air tightness testing can become helpful. More likely though in these small cottages apart from the questions of economics is space considerations, for whilst systems are increasing all the time, the unit itself and ducting need careful planning.

image 19 Harbour Festival large landscape by D. Rigamonti

ref 35 Ventaxia HR100R/RS

[edit] Concluding comments

We have talked through a hotchpotch of ideas in this article, we haven’t and couldn’t have covered all of the technical possibilities which all might also be part of a mix. Whilst larger village wide systems may also prove to be the best route, from growing biomass on the estate to heat networks or large-scale wind turbines, which are all possible future scenarios.

“the idea of wind turbine doesn't turn me off at all I think, and I think, you know in about 20 years’ time people would think of them in the same way as they think of 17th century windmills at the moment you know, they've got to be preserved because we love the motion of them or whatever. So, no I don’t rule out the idea of a turbine for the village. Where I slightly resile from would be question of supplying it and the admin of charging people for electricity consumption if one had to do it that way right, but perhaps there’s a clever way of doing that. And of course, we are an AONB an area of outstanding natural beauty and therefore there may be complications or restrictions, but I'm perceptive to that idea and probably yes that would could be the easiest solution seems to make the most sense because it is a wind, windy area”

Whilst at the same time a simple but often left out parameter in the conversations about efficiency, though something that has for other reasons gained some popularity in the tiny house movement is the aspect of size. By default and by the nature of history many of the properties we are talking about are cottages, if you like a historical tiny houses. As such the impact of these small dwellings, and the small compact lifestyle that goes with them is inherently more efficient than many modern homes just because of footprint. At the same time in terms of the efficiency of their inherent fabric historically already invested carbon (as opposed to new build carbon) is often overlooked.

It is understandable that these kinds of calculations may be a step to far for the average EPC but if there is growing evidence that historical buildings perhaps are more likely to suffer unfair ratings because of pre 1900s or later default values, perhaps these other aspects should also be taken into consideration. We talk about operational carbon and embodied carbon, which is a way a misnomer because embodied carbon in many cases is the operation carbon of current industries and the manufacturing materials. If reducing emissions is about reducing emissions spent now, then existing buildings and their upkeep are starting on more solid ground, yet despite this they continue to be given a financial advantage in terms of taxation and perhaps it seems in terms of efficiency. There perhaps needs to be a further sense check or review of how current funding schemes impact historical buildings because of the reasons described.

In summary my own impression of the approach to the restoration of the village taken by the Clovelly estate, find is a refreshingly realistic and practical, one of step changes made with care and caution, based on a long-term financial strategy with a view to longer term sustainability. They have done so in many ways, as many historical buildings do somewhat against the odds in terms of taxation, grant funding, technology and assessment of efficiency improvements. On discussing the ideas of net zero planning for such a place, whilst he is obviously very perceptive to the ideas of sustainability, improving efficiency and reducing waste, Mr Rous gave a typically frank and practical response which again simply makes good sense.

“that, to me that sort smacks a bit of Stalinism to me, kind of like here is our 20 year plan and we are going to do this and ignore anything that happens after year 5 and carry on regardless. I’m much more with sort of Newtonian approach, with gradual improvements here and gradual improvements there and refinement of the processes as you go along and as you learn and get a bit cleverer. So no, that approach intellectually doesn’t appeal to me at all.”

Finally, perhaps as part of this there needs to be a constant re-evaluating of what we mean by value in the context of historical buildings. Something described by Seán O’Reilly Director of IHBC in a recent interview on Designing Buildings 36

“Value brings up many other associated themes that inevitably feed into economics, financing and on the ‘cash’ side, and also indirectly, when we talk about social value, cultural value, community value, carbon value and so on, where heritage value is inherent in and tied to economic values. So reservations in discussing finance must also be coupled with an appreciation of in relation to the wider context of economic generation as well as savings in other areas, for example climate change-related costs, which in turn links closely with other disciplines. In a world of subsidies for new build but not for maintenance, repair or refurbishment, heritage is still too often seen as a constraint rather than the opportunity that it increasingly offers. This is particularly so in the context of other values and pressures that many projects face from land values through to environmental considerations.”

Featured articles and news

BSRIA Statutory Compliance Inspection Checklist

BG80/2025 now significantly updated to include requirements related to important changes in legislation.

Shortlist for the 2025 Roofscape Design Awards

Talent and innovation showcase announcement from the trussed rafter industry.

OpenUSD possibilities: Look before you leap

Being ready for the OpenUSD solutions set to transform architecture and design.

Global Asbestos Awareness Week 2025

Highlighting the continuing threat to trades persons.

Retrofit of Buildings, a CIOB Technical Publication

Now available in Arabic and Chinese aswell as English.

The context, schemes, standards, roles and relevance of the Building Safety Act.

Retrofit 25 – What's Stopping Us?

Exhibition Opens at The Building Centre.

Types of work to existing buildings

A simple circular economy wiki breakdown with further links.

A threat to the creativity that makes London special.

How can digital twins boost profitability within construction?

The smart construction dashboard, as-built data and site changes forming an accurate digital twin.

Unlocking surplus public defence land and more to speed up the delivery of housing.

The Planning and Infrastructure Bill

An outline of the bill with a mix of reactions on potential impacts from IHBC, CIEEM, CIC, ACE and EIC.

Farnborough College Unveils its Half-house for Sustainable Construction Training.

Spring Statement 2025 with reactions from industry

Confirming previously announced funding, and welfare changes amid adjusted growth forecast.

Scottish Government responds to Grenfell report

As fund for unsafe cladding assessments is launched.

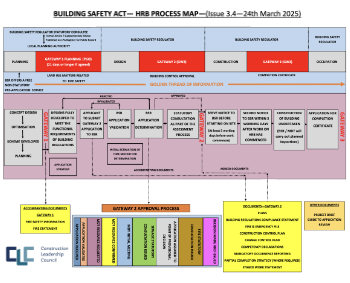

CLC and BSR process map for HRB approvals

One of the initial outputs of their weekly BSR meetings.

Building Safety Levy technical consultation response

Details of the planned levy now due in 2026.

Great British Energy install solar on school and NHS sites

200 schools and 200 NHS sites to get solar systems, as first project of the newly formed government initiative.

600 million for 60,000 more skilled construction workers

Announced by Treasury ahead of the Spring Statement.