The history of timber construction in the UK

Contents |

A timber Stonehenge

Stonehenge has a long history. The same site was in use for over 4,000 years with evidence of an early period with wooden structures similar to the ones in stone that are now there. At this time the area around Stonehenge would have been a dense Scott's Pine forest.

In his 1987 book John North documented many sites in the Avebury region as well as other stone age sites in England. His thesis was that stone age people were fascinated by the stars and built major monuments both in wood and stone to observe them, such as Durrington Walls, a wooden site three km North East of Stonehenge. The only things left of this site today are ditches and the remains of post holes. Durrington Walls was active from about 2450 BC and the site was used for over a century. John North suggests the alignment of the axis of the monument was related to the sun, moon or star alignments in much the same way as Stonehenge.

If North's reconstruction is accurate, Paleolithic people were quite capable of making complex wooden objects and building monumental structures from wood. Yet the general consensus is that wood was not used as a building material for places to live. As many stone dwellings are found, scholars believe that stone dwellings were the norm. That is a little odd, as wood is much easier to work than stone, so one would expect many wood dwellings from this period.

A timber London

The first 'London Bridge' was Roman and was probably built from timber. However the earliest written reference to a London Bridge can be found in the section in the Saxon Chronicles that deals with the latter half of the 10th century. The Roman and Saxon wooden London Bridges were vulnerable to fire and flood so Peter de Colechurch determined to build a lasting bridge of stone.

There were houses on and around the bridge, of timber frame with wattle and daub walls. Haute-pas galleries from the third storey linked the houses on either side of the Bridge road. Shops would have had painted signs with counters that projected out into the street. The houses overhung the bridge and were supported by timber beams. The piers or starlings of the Bridge were constructed from a ring of elm beams driven into the riverbed which enclosed loose stone rubble, across which were laid oak beams. Then there was an outer layer of wooden beams which also enclosed more rubble. The width of the piers was extended over the years, meaning that the flow of the river became very restricted. Many people lost their lives trying to negotiate the bridge rapids.

The first regulations

A set of 'building regulations' dating from 1200 tried to tackle issues of human waste and water, access to light and party walls and most importantly fire, one of the greatest hazards these dense cities. In 1212, a major fire led to thatched roofs being banned in London by the city's first mayor, Henry Fitzailwin. Construction and use was often advised by masons and carpenters.

Other cities began similar initiatives and by 1400 Bristol and Worcester had appointment an early form of a building inspector and thatched houses and timber chimneys were banned, whilst stone, brick and tile were seen as safer materials. However, timber-frame houses continued to be erected for centuries, with space being tight, the flexibility of timber frame with infill, facilitated storeys on storeys, and overhangs to maximise the built area on site.

The fire regulations

The Great Fire of London began on the night of September 2, 1666, as a small fire on Pudding Lane, in the bakeshop of Thomas Farynor, baker to King Charles II. At one o'clock in the morning, a servant woke to find the house alight, and the baker and his family gone, the servant perished in the blaze. The fire moved to the hay and feed piles on the yard of the Star Inn at Fish Street Hill, and spread to the Inn. Strong wind sent sparks that ignited the Church of St. Margaret, and then spread to Thames Street, with its riverside warehouses and wharves filled with hemp, oil, tallow, hay, timber, coal and spirits.

The citizen firefighting brigades had little success containing the fire with buckets of water from the river. By eight o'clock in the morning, the fire had spread halfway across London Bridge. The only thing that stopped the fire from spreading to Southwark, on the other side of the river, was the gap that had been caused by the 1633 fire. Most London was made from dense wood and pitch buildings. The fire wiped out nearly 80% of the city.

Charles II appointed six Commissioners to redesign the city. The plan provided for wider streets and buildings of brick, rather than timber. By 1671, 9,000 houses and public buildings had been completed. The disaster led to the London Building Act of 1667, the first to provide for surveyors to enforce regulations. Storeys and widths of walls were specified and streets were to be wide enough to act as fire breaks. The later Acts of 1707 and 1709 extended controls to Westminster, adding a prohibition on timber cornices and requiring brick parapets. The comprehensive Act of 1774 covered the whole built-up area of London.

200 years later

The first timber frame building to be allowed in the centre of London since the great fire of London was the reconstruction of the Globe Theatre in Southwark, completed in 1997.

The historical event that started in Pudding Lane still has some influence on attitudes and uses of timber in urban buildings across the UK, as the express purpose of the very first set of buildings regulations were indeed to effectively ban the use of timber. However the vernacular of the half-timber houses was a key part of English construction and remained so in smaller towns and rural areas as a testament to the charm of mediaeval and Tudor England.

English timber-frame

Until the 17th century, England had an abundant supply of oak, which was the most common material used for timber frame, as it is hard and durable. This is why so many mediaeval half-timbered buildings have survived.

The term "half-timbering" refers to the fact that the logs were halved, or a least cut down to a square inner section. In other areas of Europe, such as Romania and Hungary, there was no comparable hard wood available and houses were more frequently constructed using softwood whole logs. Unlike modern framed buildings where the walls are installed outside and inside the frame, in half-timbered buildings the walls are in-filled in between the structural timbers. The most common infill was wattle-and-daub (upright branches interwoven by smaller branches and covered by a thick coat of clay mud), laths and plaster, or bricks.

A perimeter footing of an impervious material like stone or brick was built first, then a sill beam laid on the footing. Upright beams were mortised into the sill beam and tenoned at the top into another horizontal member. Timber framed houses were essentially big boxes, with upper "boxes" (stories) set upon lower ones.

Often the upper floors projected out over the lower ones. There are several conjectures as to the reasons for this. One is that houses in cities were taxed on the width of street frontage they used. So a high, narrow house saved the owner money, yet to maximise interior space the non-taxed upper floors were lengthened. Also, the projecting upper floors helped protect the lower house from rain and snow in the days before gutters and down-pipes.

The construction methods used in half-timbering allow buildings to be easily dis-assembled and put up again elsewhere. This has helped salvage houses which would otherwise have been destroyed to make way for new development. Many mediaeval timber-framed houses have been re-erected at open air museums such as the Weald and Downland Museum at Singleton, West Sussex, and the Avoncroft Museum of Buildings at Bromsgrove, Worcestershire.

By the 15th and 16th century timber framing began to be exploited for its decorative qualities. Timbers which had minimal structural importance were added to the frame to enhance the decorative effect of dark wood set into whitewashed walls. The Jacobean period saw this carried to extremes.

By the Jacobean period wood for timber framing was in short supply in England. For too many years wood had been used for building, heating, and for making charcoal. Also, the great expansion of the British merchant fleet and after the mediaeval period used up large quantities of wood. Finally, the introduction of cheap, easily available bricks after the Tudor period provided an attractive alternative to half-timbering.

Other examples of historic timber buildings in UK can be found in coastal areas and are generally related to water activities such as fishing. On the south coast tall wooden huts, that were once used by fishermen for drying their nets and storing their gear, still stand by the beach at Hastings. They date back to Elizabethan times and were built tall and narrow to reduce ground rent. They are timber structures clad in timber and painted with a black bitumen tar to protect them. This type of cladding is known as “weather boarding” and consists of lapped timber panels.

The same style of cladding can also be seen on dwellings in these areas or on the recreational beach huts from the Victorian ages. Though timber as a cladding material was not so very common in England there is much evidence to suggest its use wide use in areas of Scotland.

Scottish timber frame

Although timber structures in Scottish towns were clad in timber boarding until a very late date, this was often ignored in the late 19th and early 20th century when the surviving buildings were demolished. This is because the cladding was, at the time of demolition, generally covered with a lime render and it is this material that is most often recorded in contemporary descriptions and illustrations.

Visual evidence for timber-clad buildings in Scottish towns survives in prints, drawings, paintings, book illustrations and architectural surveys. Lamb (1895) illustrates and describes a number of timber ‘lands’ surviving in Dundee until the 1890’s, and the same type of evidence survives in other towns, for example in folios of drawings showing the streets and closes of Edinburgh. Unfortunately, whilst evidencing timber-fronted buildings, these drawings seldom show constructional details.

In mediaeval Scotland, as in much of Europe, oak was the preferred structural and finishing timber. Converted into boards by cleaving the log along its length, this technique required straight-grained and knot-free timber, with the board lengths determined by the distance between knots. The log was split into wedge-shaped segments, with the central core and sapwood removed (the width of each board had to lie within the radius of the log, making allowance for the removal of the centre of the log and the sapwood). It therefore required a log of at least 750mm (2ft 6in) diameter to produce a 300mm (1ft) wide board. Oak shingles appear to have been a popular roof covering on high-status buildings in Scotland until the late 17th century, and were produced by cleaving in the same way as boards.

The use of European oak for external cladding in Scottish towns gave way to Scots pine in the late mediaeval period. Exactly when this occurred is uncertain, but new trade developed with south-west Norway around 1500 and this is likely to have been an important factor. The ‘Scottish Trade’ (Skottahandelen) with Norway was a direct trade between the skippers of Scottish ships and local farmers in the Ryfylke region of Norway. It was a barter system: the Scots traded cereals for timber (mainly redwood but with occasional oak), whilst avoiding the customs duties of Stavangar, the trading port. The Scottish Period ‘Skottatida’ lasted from c.1500 to 1717 when Stavanger imposed a ban on the Scots and other foreigners sailing up the fjords to trade. Half the Scottish ships came from Fife and a quarter from Tayside, Dundee providing the largest number from a single port. Homegrown Scots pine was also utilised when available, although supplies were intermittent.

The introduction of stone and brick as well as the dwindling amounts of available timber lead to a vast reduction in the number of timber buildings.

This historical background is important as it stands as a kind of preconditioning for the use of timber, which in the last few years has seen somewhat of a comeback, albeit more often with European timber than UK grown hardwoods.

Timber in modern construction

Oak frame houses are now more common than 10-15 years ago. The Oak often comes from France and is used in a green (freshly cut) state. In terms of the reasons for using timber in buildings, modern oak frames are a strong part of the vernacular tradition of the country, the timber is untreated and can be sourced quite locally and can be used both in traditional styles and modern styles. The main limitation is purely one of cost as the timber is quite expensive as well as the labour being skilled and sometimes costly.

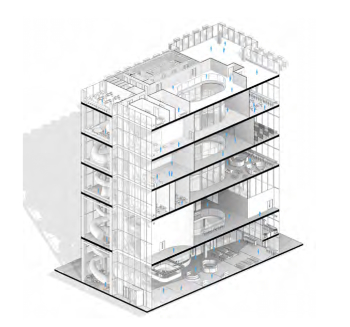

Brick-clad timber, balloon frame buildings, have been around for a long time, and are commonly seen in the UK, primarily in the low-rise housing market. However with the introduction of cross-laminated massive wood construction and further research of softwood framed buildings and fire studies, taller buildings of 5 storeys or more might be seen. However timber frame buildings both low and high rise continue to fuel debate from the perspective of fire as well as moisture control, but also for the environmental capacity of timber to sequester carbon.

Timber cladding on buildings in the UK during the 80's and 90's was often reserved for building statements or low impact buildings, but has gradually become more mainstream. Products such as sweet chestnut cladding, grown from UK based coppice forests (which create reduced soil disturbance emissions) represent some promising opportunities to re-invigorate this traditional industry.

UK Forestry

Timber is one of the UK's biggest imports, yet at the same time many native woodlands suffer from neglect. Sustainable management of woodlands is key in meeting environmental obligations, yet at the same time the production from woodlands could help support environmentally beneficial business', based on adding-value to local resources.

Timber is a renewable resource, capable of producing a wide range of products, from fuel wood to fine furniture. Restoring woodlands to a managed state will benefit biodiversity, and help create employment. By recognising the value of the natural assets of woodland, as a place for wildlife, people, and as a source of useful timber, a reduction in imports might be achieved, thus reducing pressure on unsustainably managed forests elsewhere in the world.

It is true that the UK Forestry industry is not as prominent as in many other countries, though historically the country was originally a forested land. So today there seems to be a drive to increase the land cover of forested areas in the UK or at least not to decrease forested land. This is seen by the increases in new planting whilst supporting the use of more UK timber within the building industry, for both economic as well as environmental reasons. In order for the timber to stay as sustainable as it can be, using timber from traditionally coppiced woods, helps reduce emissions from soil disturbance whilst using locally produced timber reduces emissions from transport.

Production of timber has increased over the last few years by a greater amount than consumption of timber, though consumption still outweighs production leading to imports. Production of softwood has also increased over the last 5 years though hardwood production as well as consumption has dramatically decreased.

In the context of land scarcity, forecast household growth, and climate change issues timber-framed construction is very likely to continue its important contribution in meeting new housing needs. The method scores highly in tight access locations with poor ground conditions, underlining its future potential for housing and related uses in urban brown field sites, despite the historical context described above.

--editor

Related articles on Designing Buildings

Featured articles and news

Future Homes Standard Essentials launched

Future Homes Hub launches new campaign to help the homebuilding sector prepare for the implementation of new building standards.

Building Safety recap February, 2026

Our regular run-down of key building safety related events of the month.

Planning reform: draft NPPF and industry responses.

Last chance to comment on proposed changes to the NPPF.

A Regency palace of colour and sensation. Book review.

Delayed, derailed and devalued

How the UK’s planning crisis is undermining British manufacturing.

How much does it cost to build a house?

A brief run down of key considerations from a London based practice.

The need for a National construction careers campaign

Highlighted by CIOB to cut unemployment, reduce skills gap and deliver on housing and infrastructure ambitions.

AI-Driven automation; reducing time, enhancing compliance

Sustainability; not just compliance but rethinking design, material selection, and the supply chains to support them.

Climate Resilience and Adaptation In the Built Environment

New CIOB Technical Information Sheet by Colin Booth, Professor of Smart and Sustainable Infrastructure.

Turning Enquiries into Profitable Construction Projects

Founder of Develop Coaching and author of Building Your Future; Greg Wilkes shares his insights.

IHBC Signpost: Poetry from concrete

Scotland’s fascinating historic concrete and brutalist architecture with the Engine Shed.

Demonstrating that apprenticeships work for business, people and Scotland’s economy.

Scottish parents prioritise construction and apprenticeships

CIOB data released for Scottish Apprenticeship Week shows construction as top potential career path.

From a Green to a White Paper and the proposal of a General Safety Requirement for construction products.

Creativity, conservation and craft at Barley Studio. Book review.

The challenge as PFI agreements come to an end

How construction deals with inherited assets built under long-term contracts.

Skills plan for engineering and building services

Comprehensive industry report highlights persistent skills challenges across the sector.

Choosing the right design team for a D&B Contract

An architect explains the nature and needs of working within this common procurement route.

Statement from the Interim Chief Construction Advisor

Thouria Istephan; Architect and inquiry panel member outlines ongoing work, priorities and next steps.