The compact sustainable city

This article is based on the seminal book ‘Cities for a Small Country’, by Richard Rogers and Anne Power, published in 2000. The text was updated in 2014 to reflect changes in policy and recent national statistics with the permission of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.

Contents |

Introduction

Making cities sustainable means making them more compact, better connected and less damaging to the environment. To do this, we need to recycle our land and our buildings, to increase the density of development and to stop our suburbs sprawling over the countryside. We need a plan of action that works from the centre outwards, layer by layer, developing existing communities and clusters of activity into a denser, closer texture.

Population growth and urbanisation

In 2008, for the first time, more than half the world’s population was living in towns and cities (1). This figure is projected to rise to between 70 and 80% by 2050, and at the same time global population will increase by two billion. 60% of the built environment necessary to accommodate this burgeoning urban population has yet to be built (2).

Whilst there is broad agreement that densely-populated urban areas should be more sustainable than less concentrated rural settlements, in fact, they create around 75% of global pollution, more than two thirds of which is generated by buildings and transport. In 2009 the Secretary General of the United Nations Ban Ki-Moon wrote, 'The major challenges of the twenty first century include the rapid growth of many cities and the decline of others, the expansion of the informal sector, and the role of cities in causing or mitigating climate change. Evidence from around the world suggests that contemporary urban planning has largely failed to address these challenges.' (3)

One hundred years of urban sprawl

In England, in 1800, just 10% of the population lived in towns and cities, now the figure is 90% and our population is projected to increase from 52 million in 2010 to 62 million in 2035 (4). Given this intensification of occupation, it is short sighted to imagine we can sustain anything other than compact lifestyles, and yet, since 1900 our cities have actually become less dense and more extensive.

Throughout the twentieth century, politicians and planners believed that moving people out of our city centres was a good thing, and many of the great architects of the twentieth century were anti-urban. In the late 60’s there was a shift in attitude in favour of inner-city renovation and moves were made to protect traditional communities, but for the most part, depopulation continued.

Terraced housing was abandoned and planned garden cities fell out of favour. Instead, growth was delivered by the expansion of unplanned suburbs, large-scale clearance of the inner cities and the construction of new mass housing estates. This re-ordering of settlements separated work from home, breaking the close integration of commerce, manufacturing, leisure and home life which is found in popular inner-city neighbourhoods as well as smaller cities, market towns and historic villages.

In some cities, the better-off moved out, leaving behind marginalised, poorer communities. In others, rapid growth had serious environmental consequences and created new social pressures. Cities became physically dispersed, traffic-bound and socially polarised.

We are now reaching the limits of dispersal and this is forcing us back to the idea of compact, dense, mixed-use, integrated cities.

Urban density

By living in closer proximity to each other, we can accommodate far more of the world’s population, use less energy, concentrate goods and services and move from one place to another more efficiently.

High density living can also be extremely desirable, as the New Town in Edinburgh and Kensington in London demonstrate. Both have at least 250 dwellings per hectare, and yet they are extremely expensive and highly sought after. In our most attractive villages and market towns it is the older houses clustered at higher densities in the centre that fetch the highest prices.

Many village homes are above shops, attics are used, houses are close to the pavement and there are rarely garages or drives. Even the leafy parts of older cities, which are dotted with small parks, squares and large abutting gardens, have at least twice the density of many modern private developments.

Traditional southern European towns and villages can have double, triple or even quadruple the density of a typical English town. Continental cities are also built at a much higher density. Their attraction lies in their ease of access to the town centre, their links with neighbours and good access to schools. People like density. These cities have a sense of place. They offer greater security, more street life and better access to open space.

Building at 50 homes to the hectare and above has created all the attractive spaces we like best. At below 50 homes per hectare, it is hard to keep shops, buses, doctors, nurseries and schools within walking distance.

New developments in England in 2001 were built at an average of 25 dwellings per hectare (5). By 2011 this had increased to 43 dwellings per hectare and on previously-developed sites, 53 dwellings per hectare (6). In London in 2009, an even higher density of 120 dwellings per hectare was achieved (7).

Despite this, in 2010, the government’s Planning Policy Statement 3 (PPS3) was revised to remove the national indicative minimum density of 30 dwellings per hectare to give local authorities the '…flexibility to set density ranges that suit the local needs' (8) a position that was re-stated in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) in 2012. The absence of policy in this area risks undoing the great progress our cities have made and returning us to the blight of urban sprawl.

Brownfield vs greenfield

To live at a higher density, we must intensity the occupation of our cities. This means not just designing more close-knit neighbourhoods, but also re-using buildings and previously-developed land (brownfield sites).

In urban areas it is hard to escape from vacant sites with hoardings around them, unwanted buildings with broken windows and battered frontages, closed-down shops, factories and warehouses and car parks sprawling across waste ground. Meanwhile there is new building on the outskirts of almost every settlement.

In 2003, the Environment Agency suggested, 'Concentrating development on brownfield sites can help to make the best use of existing services such as transport and waste management. It can encourage more sustainable lifestyles by providing an opportunity to recycle land, clean up contaminated sites, and assist environmental, social and economic regeneration. It also reduces pressure to build on greenfield land and helps protect the countryside.' (9).

In 1998, to encourage the re-use of previously-developed land, and reduce suburban sprawl, the government set a national target for 60% of all new developments to be built on brownfield land. In 2009, local authorities identified 61,920 hectares of previously-developed land in England that could be available for development (10), and it was estimated that 80% of new dwellings were built on previously-developed land (11).

However, as with urban density, this good progress is in danger of being undone. Under the pressure of a projected shortfall of 750,000 houses by 2025, (12), the 2012 National Planning Policy Framework did not include a brownfield target, but rather it ‘…encourages local authorities and their communities to decide where is best to locate development’ (13). In an interview on BBC2’s Newsnight in November 2012 (14), planning minister Nick Boles, suggested that a staggering 388,000 hectares of open countryside would have to be built on over the next twenty years to meet housing demand, that’s an area twice the size of Greater London.

Boles stated that nine per cent of England had been built on, but this needed to increase to 12 per cent suggesting that ‘…if people want to have housing for their kids they have got to accept we need to build more on some open land', only offering explicit protection for green belt land around towns and cities (15). In December 2013, a survey by the National Trust found that 51% of the councils with green belts in their areas were likely or very likely to allocate green belt land for development (16).

Dramatically increasing the built area of England in this way will not only further destroy our countryside, it will reverse the gains that have been made, seriously exacerbating the problems of urban life just at the time when it is vital that we correct them.

In 2011, just 68 per cent of new dwellings were built on previously-developed land (NB from 2010 residential gardens were excluded from the previously-developed land category) (17)

Mixed use, evolving cities

Cities and towns have the potential to be the most efficient, the most ecologically sensitive and the most equalising environments. However, the future of our cities cannot be about carrying out a clean sweep, it can only be about fitting in with the grain of our already-built environment.

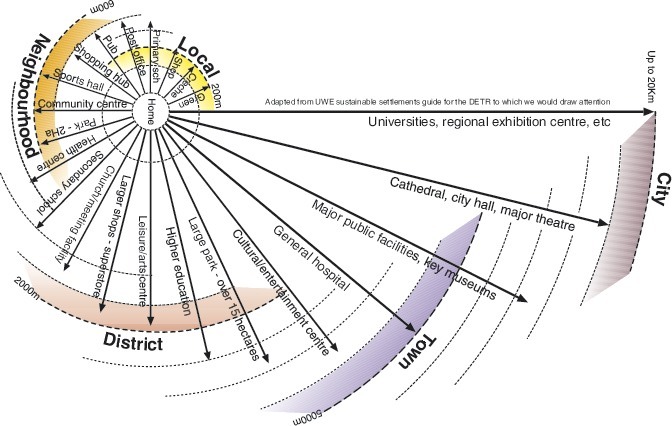

Mixed-use, closely-knit neighbourhoods ordered around streets and squares are the archetypal human settlement. Popular inner neighbourhoods, smaller cities, market towns and historic villages are often slowly evolving communities where the church, the pub, the village street and its shops, the green, the square, the cemetery and the bus stop make up a pattern of public spaces that help people organise their lives in a socially and spatially-connected way.

The more slowly the physical structures adapt, the more blended and harmonious they become. Surviving medieval street patterns in London, York and Edinburgh are still functioning and appealing today. In slowly-evolving cities, the proportions, scale and grain of the buildings, their juxtaposition and their interaction with the environment creates a powerful sense of place.

We like historic cities and vibrant capitals. We enjoy landmarks new and old, the blend of history and modernity, that settled-in feel and the thrill of change, new activities alongside and within old buildings. We like compact small towns, we like village centres. Our more attractive cities are humming with vitality, a mix of work, home and leisure, a dense pattern of land use adapted over time that would be hard to create from scratch.

This does not mean we cannot plan, but we need to do it more carefully. It is vital to identify simple core goals that everyone supports so that we can escape the circus of developers blaming planners who blame developers. Both blame politicians and argue that they are ‘demand driven’. The green belt, one of the truly monumental planning achievements of the twentieth century, is a good model. It is simple, popular, enforceable and fair.

Planners can help create sustainable compact cities by applying simple and enforceable rules:

- Brownfields and empty buildings first.

- Higher density.

- Compact design.

- Mixed uses.

- Sustainable energy.

- Minimal environmental impact.

Transport

The less dense cities are, the further they sprawl, the worse the traffic problems are. We travel further to work, to school, to shop. Children cannot play safely, cannot cross the road. In London, congestion means that cars travel at about the same speed as horse-drawn carriages did in 1880. By 2031, the population of London is forecast to increase from around 8 million to 9.2 million, potentially worsening congestion by 17% (18).

Providing new transport options within and, most importantly, between neighbourhoods is essential. People should be able to walk into the centre of their neighbourhood to find shops, doctors and efficient public transport networks. From every neighbourhood it should be possible to travel quickly, cheaply and comfortably to places of employment and entertainment.

In successful cities, people dominate the streets. In terms of transport, this can be encouraged by:

- Restricted parking.

- Subsidised public transport.

- Traffic calming and pedestrianisation.

- Home zones where pedestrians have absolute priority.

- Tramlines and buses, bicycles and pedestrians with priority over cars.

- Integrated transport that cuts across local authority boundaries.

- City-wide flat fares on buses.

- Family tickets.

- Clear information, good lighting and staff to make vulnerable passengers feel safe.

- Accessibility for people with mobility problems.

- New high-speed railways transforming the pattern of investment.

The compact sustainable city

We can work within the grain of cities, we can restore their compactness; a revival of clustered, higher-density settlements that follow popular patterns. We can rebuild our cities by taking simple steps, block by block, street by street:

- Designing more attractive, more compact, more sustainable settlements that hold on to urban residents and attract new talent.

- Creating city centres where people can gather, where services thrive and multiply, where activities intermingle, where public spaces draw people in, where public transport minimises the impact of the car and maximises social contact.

- Treating land more responsibly, recycling it more often and regenerating run-down buildings.

- Creating mixed use neighbourhoods with affordable homes and a broader social mixture of people. Urban villages that give people a sense of identity.

- Providing gardens, squares, parks and access to open country. With the involvement of the local community, greening even the tiniest of spaces.

- Renovating, managing, diversifying and densifying suburbs so they become neighbourhoods in their own right, connected to city centres without the need for cars.

- Organising services more efficiently to make our cities cleaner, safer and more attractive.

- Moving people within and between neighbourhoods in larger numbers by more concentrated methods to make our streets more people friendly.

- Creating effective systems of bottom-up governance that encourage regional identity, combining grass-roots involvement with strategic vision.

- Providing safer, cleaner neighbourhoods with effective management, local co-ordination and hands-on control.

Conclusion

The changes sweeping across societies in the developed and developing world are played out most powerfully in cities. This is because cities concentrate not just problems, but also solutions. Cities hold the key to our common future.

To make cities work at both the widest and the most local level, to fit together the hundreds of elements needed, is a complex task. It requires not just vision, but architecture, engineering, social and communications skills, organisation and leadership. Compact cities are at the opposite pole to urban sprawl, to achieve success they need many groups to work together. Teamwork is the key.

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- 15 minute city.

- Access and inclusion in the built environment: policy and guidance.

- Allotment.

- Biophilic design.

- Brasilia Syndrome.

- Brownfield land.

- Compact living.

- Congestion in historic cities.

- Contaminated land.

- Densification.

- Gentrification.

- Green belt.

- Eco towns.

- Garden cities.

- Garden town.

- How can cities become more resilient?

- Hub and spoke model.

- Masterplanning.

- Measuring the success of smart cities.

- National Planning Policy Framework.

- Neighbourhood planning.

- Place.

- Placemaking.

- Planning for sustainable historic places.

- Post pandemic places report.

- Redefining density, making the best use of London’s land to build more and better homes.

- Richard Rogers.

- Smart cities.

- The future of the green belt. 2015

- Town planning.

- Urban Task Force.

References

- (1) United Nations Population Fund: Linking Population, Poverty and Development.

- (2) United Nations Environment Programme: City-Level Decoupling: urban resource flows and the governance of infrastructure transitions, 2013.

- (3) UN Habitat: Global Report on Human Settlements, Planning Sustainable Cities, 2009.

- (4) Office for National Statistics: UK Population Projected to Reach 70 Milllion by Mid-2027,2011

- (5) Department for Communities and Local Government, Land Use Change Statistics (England) 2009 - provisional estimates (May 2010).

- (6) Department for Communities and Local Government. Land Use Change Statistics in England: 2011

- (7) Department for Communities and Local Government: Land Use Change Statistics in England: 2010 provisional estimates, 2011.

- (8) House of Commons Library. Housing Density, Brownfield Sites and Gardens, 2012.

- (9) Environment Agency: Brownfield Land Redevelopment: Position Statement. 2003

- (10) Homes and Communities Agency: Previously developed land that might be available for development, 2009.

- (11) Department for Communities and Local Government. Land Use Change Statistics in England: 2010 provisional estimates July 2011.

- (12) Institute for Public Policy Research: England faces 750,000 housing gap by 2025, 2011.

- (13) Brownfield Briefing: Coalition stresses commitment to brownfield, 2013.

- (14) BBC News: Open land can solve housing shortage, says minister, 2012.

- (15) Telegraph: Government minister warns we must develop a third more land to meet the housing demand, 2013.

- (16) National Trust. Planning policy could put green belts at risk. 19 December 2013.

- (17) Department for Communities and Local Government. Land use change statistics in England: 2011. 19 December 2013.

- (18) New London Architecture, Planes, trains and drains, London’s booming infrastructure business, associated publication, 2013.

- DCLG: House Building: December Quarter 2013, England.

Featured articles and news

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.

Heritage staff wellbeing at work survey.

A five minute introduction.

50th Golden anniversary ECA Edmundson apprentice award

Showcasing the very best electrotechnical and engineering services for half a century.

Welsh government consults on HRBs and reg changes

Seeking feedback on a new regulatory regime and a broad range of issues.

CIOB Client Guide (2nd edition) March 2025

Free download covering statutory dutyholder roles under the Building Safety Act and much more.

Minister quizzed, as responsibility transfers to MHCLG and BSR publishes new building control guidance.

UK environmental regulations reform 2025

Amid wider new approaches to ensure regulators and regulation support growth.

BSRIA Statutory Compliance Inspection Checklist

BG80/2025 now significantly updated to include requirements related to important changes in legislation.