Interwar: British architecture 1919-39

|

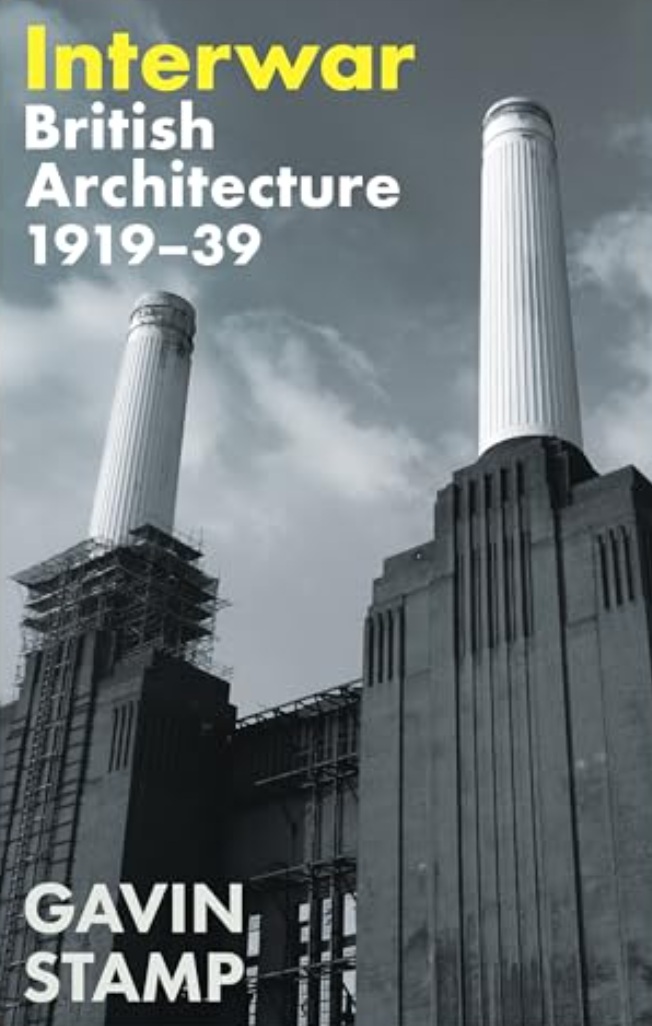

| Interwar: British architecture 1919–39, Gavin Stamp, Profile Books, 2024, 576 pages, numerous black-and-white and 38 colour illustrations, hardback. |

The late Gavin Stamp will need little introduction to the readers of Context. He was an eminent historian who was also a highly effective campaigner for the protection of what were often neglected aspects of the historic environment through his journalism and as an active chairman of the Twentieth Century Society. At his death in 2017 he left behind an unfinished manuscript for a comprehensive survey of British architecture between the two world wars. The project had preoccupied him throughout his career and we must be grateful that his widow, Rosemary Hill, in partnership with the Twentieth Century Society, has brought it to fruition with this weighty book.

It was a period of enormous economic and social change which was reflected in the declining influence of the British Empire and the rise in dominance of the USA. Architecturally it was characterised by the potential of new building materials such as reinforced concrete, stainless-steel girders and plate glass. These were used to meet the demand for speculative suburban housing estates, power stations, public libraries, post offices, cinemas, petrol stations, ocean liners and skyscrapers, among many other distinctive building types. They were dressed in a bewildering variety of styles, wonderfully lampooned by Osbert Lancaster in his books Pillar to Post (1938, John Murray, London) and Drayneflete Revealed (1949, John Murray, London). Stamp’s admiration for Lancaster, John Betjeman (from whom he inherited his fortnightly column in Private Eye) and the satirical novels of Evelyn Waugh is reflected in quotations throughout the book, which greatly enliven the prose.

The introduction highlights the stylistic diversity of interwar architecture with no single dominant theme. Gothic and classical remained valid architectural choices, as well as more recent trends like arts and crafts. Stamp upholds that the neo-Tudor suburb and the art-deco factory are just as important as flat-roofed concrete houses in seeking to understand British architecture between the two wars. The chapter headings neatly capture the broad cultural episodes of the era and place them in chronological order. The first is Armistice, which looks at how the large number of war memorials commemorating the horrors of the first world war culminated in the Memorial to the Missing of the Somme, which Stamp considered ‘the greatest British work of architecture of the interwar years’, albeit erected on the other side of the English Channel.

The next chapter, entitled The Grand Manner, opens in India with similar praise for New Delhi as a continuation of the classical tradition which remained the preferred choice for many civic buildings and banks at home. Swedish Grace explores the growing influence of the architecture of northern Europe, France and Scandinavia, while Brave New World focuses on the contribution derived from America. The discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun prompted a brief period of Egyptomania, which found its most accomplished expression in art deco, and Merrie England captures the popularity of the neo-Tudor revival, which Stamp describes as ‘a type of architecture which deserves to be taken seriously even if difficulties are presented by the hostile attitude of most contemporary literature and by the anonymity of the ordinary suburban house.’

The New Georgians describes the continuing attraction of classical and regency styles for public buildings and municipal housing estates through the 1930s. Paradoxically, it was also the decade which saw the demolition in London of Georgian terraces, Nash’s Lower Regent Street, the Adelphi by the Adam brothers and Rennie’s Waterloo Bridge, leading to the founding of the Georgian Group in 1937. Modern Gothic is devoted mainly to churches, of which a large number were built to serve the new suburbs, many of them influenced by contemporary work on the continent and the continuing association in Britain between gothic principles and Christianity.

The final chapter, The Shape of Things to Come, tackles the thorny question of the true impact of international modernism on the architectural legacy of the period. Its undoubted importance can be easily exaggerated by later critics and historians. Stamp presents a more balanced view, suggesting that it was only really acceptable for particular building types, such as health centres and places of entertainment, or in fringe locations such as by the seaside. In a telling comparison, he points out that FRS Yorke in his book on The Modern House in England (1937) Architectural Press, London, could choose only 49 houses to describe at a time when more than four million new homes had been built in the period between the two world wars.

As one would expect from Gavin Stamp, this is a provocative as well as a stimulating book. He has his heroes, some of whom he has written about before. Sir Edwin Lutyens and Sir Giles Gilbert Scott are duly praised, but he also includes less well-known architects like Arthur Shoosmith. There are villains, too, including Sir Herbert Baker, castigated for mutilating Soane’s Bank of England. Stamp’s conclusions are supported by extensive quotations from the literature of the period and are lavishly illustrated by excellent photographs of examples from Britain and abroad. The architecture of Scotland, Ireland and Wales is given equal space with that of England, and he has diligently credited the names of the architects who were responsible. Rosemary Hill’s helpful foreword emphasises the book’s value to an understanding of twentieth-century history in a rapidly changing world. It can be thoroughly recommended as a fitting tribute to someone whose contribution to the conservation movement in this country continues to be appreciated.

This article originally appeared as ‘Bewildering variety’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 181, published in September 2024. It was written by Malcolm Airs, past president of the IHBC.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Conservation.

IHBC NewsBlog

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.

National Audit Office (NAO) says Government building maintenance backlog is at least £49 billion

The public spending watchdog will need to consider the best way to manage its assets to bring property condition to a satisfactory level.

IHBC Publishes C182 focused on Heating and Ventilation

The latest issue of Context explores sustainable heating for listed buildings and more.

Notre-Dame Cathedral of Paris reopening: 7-8 December

The reopening is in time for Christmas 2025.