Types of rapidly renewable content

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

The term rapidly renewable content describes material that contains biomass harvested in cycles of less than ten years (for certain materials these cycles may vary).

Although it depends on the later manufacturing and delivery processes involved, these materials often have lower environmental impacts because of their shorter regenerative and carbon sequestering cycles, they create less soil disturbance and often require less energy to harvest. It depends on land use, vegetation and climate but there is more carbon stored globally in soils than in vegetation and the atmosphere combined, with higher levels of soil carbon found in bushy, non-woody vegetation than in forests. However, soil and root disturbance can lead to the release of soil-based carbon stores. Shorter harvest rotations mean smaller mass and less invasive techniques to extract materials, such as low-level stem cutting or growing without soil. Short or longer coppicing and pollarding techniques leave tree roots intact, creating less soil disturbance and releasing less soil-based carbon.

An increasing number of construction materials are being researched and developed from these types of materials as well as their by-products and waste, along with ash or biochar made from them.

In this list, examples are given and categorised by their indicative harvesting methods, the list is not exhaustive and these types of material are currently expanding significantly. A certain number of materials may also fall into other categories of product or material, such as bio-based or biogenic materials. For example, fungi based materials, often referred to as biogenic, are also rapidly renewable but not often described as such.

[edit] Agricultural crops and by-products

There are a vast number of agricultural crops that have been harvested as foodstuffs for centuries, many of these crops will produce biowaste either from the process of farming (whole stalks, grasses, leaves, bark or marrow) or through preparation and removal of the edible element (husks, shells or bagasse). Here are a list of some of these crops describing which elements are useful in the manufacture of construction products.

[edit] Cereals

The world crop database includes some 26 cereal crops, the most significant being corn or maize (zea mays), Asian (oryza sativa) or African rice (oryza glaberrima) and wheat (triticum aestivum) of various varieties. Wheat, Rice and Corn all take around 4 months to mature and to be ready to harvest. They are primarily a food crop used to make flour. These crops are all grasses that are primarily cultivated for their seeds, the grass in effect being a by-product, used traditionally as bedding or feed for animals and in construction such as for thatch or straw bale construction. The husks are the inedible shell of the edible grain kernel and the cob is the part of the cereal crop that holds the kernels in place such as with corn cobs, these are waste used as feed and also in construction. The fibrous or woody qualities have more recently been shown to have potential use in the manufacture of innovative board products and as mix additives. The ash or biochar of the husks and grasses have also been investigated as potential cement additives. Other cereal crops include barley, millet, crab and canary grass, oat, rye sorghum and fonio.

[edit] Linseed

Linseed (linum usitatissimum) is a crop grown either for its fibre (fibre flax) or for its oil (oilseed flax) and harvested yearly. It is used in the production of linoleum flooring and putty as well for insulation and composite board materials, research has also been conducted on its use as fine fibre reinforcement.

[edit] Cotton

Cotton (gossypium arboreum) is a crop that takes between 6-8 months to mature and to be ready for harvest. It is grown primarily to produce fibre products a swell as cottonseed oil, in construction cotton fabric may be used as part of weather proofing systems along with a waterproofer. The recycling of cotton based products has also led to its use as cotton bat insulation, as reinforcement and in blocks. Historically it has been used for tent material, and it is still sometimes used for short-term, small-scale fabric structures.

[edit] Sunflower

Sunflower (helianthus annuus L.) is a crop that takes between 4-5 months to mature and harvest. It is grown for its oil, seeds and as a bio-fuel. Research into the residue left after oil extraction, often referred to as press cake, has shown potential for its use to make glues and thin film materials. The agricultural waste stalk bark and marrow have been used to produce board material a swell as light insulation board.

[edit] Hemp

Hemp (cannabis sativa & cannabis indica.) is one of the fastest growing plants, from seed to a plant and ready to harvest takes 90-120 days, and it has been used to produce fibres for many thousands of years. It consists of about 25% long fibrous bast, a strong material for textiles and rope making and 75% short fibre core. Today, industrial hemp is used to manufacture paper, rope, textiles, clothing, biodegradable plastics, paint, insulation and biofuel. It is also used in foodstuffs, animal feed, as well as for medicinal purpose. It is also grown to produce marijuana, which is still illegal in many countries, and is the same plant containing higher levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

[edit] Kenaf

Kenaf (hibiscus cannabinus) part of the malvaceae or mallow family is often seen as an alternative to industrial hemp. It takes slightly longer to mature in a growth cycle and harvest, around 120-150 days. It consists of about 40% long bast fibre, not quite as strong as the hemp equivalent, similar to wood fibre and 60% short fibre core, which is highly absorbent. It can also be used to manufacture paper, textiles, clothing, biodegradable plastics, paint, insulation and biofuel with very similar properties to hemp. It is however a totally legal plant crop.

[edit] Sugarcane bagasse

Sugarcane bagass (Saccharum officinarum), bagass come from the French for waste or residue and refers to the biomass left after processing sugar cane. Agave bagasse describes the same. This residue is stored in different ways, depending on its use. Dried bagasse is chemically made up of: 45-55% Cellulose, 20-25% Hemicellulose, 18-24% Lignin, 1-4% Ash, <1% Waxes. Its properties therefore suit the manufacture of printing paper, newspaper, cardboard, plywood, particle board, coreboard and biodegradable plastics. It can also be employed in the production of furfural (C4H3O-CHO), a clear colourless liquid which is used in the synthesis of chemical products such as nylon and solvents as well as oils and rubber.

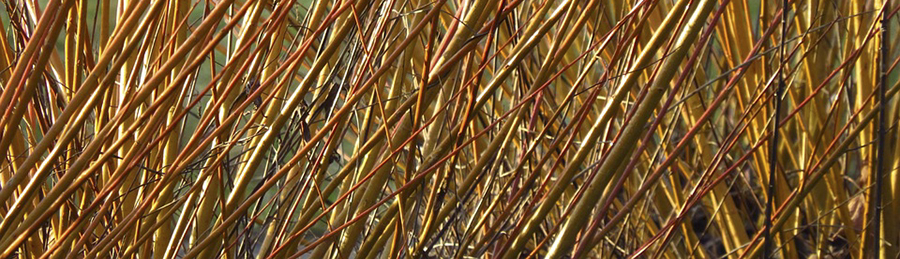

[edit] Willow (short rotation coppice SRC)

Although coppicing is generally considered a forest trade, short rotation coppice creates thinner stems that allow them to be harvested more similar to agriculture by hand or machine. Willow (salix spp.) can be grown in short cycles of 2, 4 or 5 years, agriculturally harvested by cutting it at its base to give tall straight 4-metre rods of willow. It has been investigated in the UK primarily as a source of a sustainable fuel because of its short harvest cycle as a hardy crop that can last some 30 years before requiring replanting. Traditionally it has been used in craft industries to make woven items such as baskets and light structures, some research has also looked at its potential use in the manufacture of board and formed composites. It can also be pollarded and coppiced.

[edit] Poplar (short rotation coppice SRC)

Although coppicing is generally considered a forest trade, short rotation coppice creates thinner stems that allow them to be harvested more similar to agriculture by hand or machine. Poplar (Populus spp.) is best grown in cycles of 4-5 years, producing taller 8-metre lengths but fewer in number. Initial plantings are from cuttings that contain buds. Once established it forms a deep string network of roots which can be difficult to remove. It has a lower bark to wood ratio and is also promoted as a biomass crop in the UK.

[edit] Fungi, mushroom and mycelium

Mycelium is one of the most rapidly renewable resources on the planet, it is not grown outside in the same way as many other agricultural products but inside darkened halls. Mycelium is the in effect the complex structure that makes up the roots of fungi and mushrooms which have been grown and harvested commercially for many years. It grows initially quite slowly, but after seven to eight days the grows exponentially, once the growing area has been colonised it will stop growing of its own accord stops of its own accord. More recently great interest has surrounded Mycelium because of its natural qualities and ability to grow rapidly, it is now used as the base for many products that can be used in buildings such as furnishings and insulation, which is fire retardant and well performing.

[edit] Forestry crops, pollarding, shredding and coppicing

[edit] Pollarding

Pollarding is a forestry method similar to pruning where the upper branches of a tree are cut back but the base and roots are left intact. It has been a common practice in the UK since mediaeval times and allowed easy removal of timber for fuel whilst encouraging greater foliage regrowth, which was used as animal feed and bedding.

Pollarded trees often lived longer, and produced denser wood as they grew more slowly. Pollarded forests when maintained may also have had a greater diversity of species because sunlight reaches deeper into the forest as higher branches are cut, along with the greater foliage. It is not however possible to pollard a tree that is already mature, hence many forests where pollarding was carried are now no longer viable for pollard forestry.

Today pollarding is commonly practised in urban environments, to prevent root invasion and control the overall size of a tree, this needs to be carried out at the right time and then repeated every few years to maintain both the look and size. It is also often carried out on fruit trees, although this may be considered more in line with pruning. In general pollarding can result in quite straight timber growths and therefore products such as fence posts and furniture legs were to be found from pollarded timber. The harvesting cycles of pollards can range anywhere between 1 to 15 years, cutting may have been quite informal with each branch and tree treated according to its own readiness, use and need. However today unless timber sources are known to be pollarded they are most likely not considered rapidly renewable.

[edit] Shredding

Shredding is the practice of cutting side branches from the main trunk of a tree while retaining the crown, typically to provide wood and fodder for livestock. Unlike pollarding, the tree is not decapitated and continues to grow upwards as a single stem tree, ultimately able to provide large dimension timber. Shredded trees are typically found alongside tracks or field boundaries and also in some pasture-woodland systems.

[edit] Simple coppicing

Coppicing in general is not considered as rapidly renewable because harvesting cycles in general are over 10 years, unless it is short rotation coppice as described which has shorter cycles. However coppicing does have harvest cycles that are shorter than many standard forestry products and as such is included here as a perhaps a forestry crop with a medium cycle rather than specifically as a rapidly renewable product. Coppicing might be described in three different approaches.

Simple coppice is where a woodland is managed with similar aged trees each with the stems cut and around head height, to produce small/medium-sized round wood for poles. Depending the size of timbers needed, the species, location, rate of growth, environmental and social requirements, the trees are cut on a regular rotation. The forest might be divided into areas that have the same harvest rotation cycle normally anything between 15 and 30 years, these grouping of trees are called coupes. This type of coppice management is called an in-cycle or in rotation coppice woodland.

[edit] Coppicing with standards

Coppice with standards is managed with differing heights of trees, in general some will be cut very low down ( called an underwood) and some very high, this gives a variety in the size of timber products that can be harvested. This approach can be more difficult to manage than simple coppicing because the species, number, age and location of taller trees needs to be balanced with their effect on the growth of the smaller trees or underwood, which is cut simply. Which trees are left for longer to grow and which cut changes with time and balanced with preventing too much over shadowing and new tree growth.

[edit] Selective coppicing

In selection Coppice, 2 or 3 cycles are used to harvest trees at the stem of differing sizes, there maybe 3 different rotations made on the same coppice stool, this provides repetition of specific size or shape products for different uses. Examples of this approach might be found in the furniture beechwood and holm oak coppice as well as hazel grown for thin straight rods that are used as thatching spars or slightly longer for fence poles.

There is some overlap between the types of species that can be coppiced and those that can be pollarded, with some of the main varieties suitable for both.

[edit] Willow coppice

Willows (Salix) are a popular UK species for both pollarding and coppicing because they are hardy and grow rapidly, they might be pollarded every 5-7 years or coppiced over slightly longer periods. Willow wood (Salix Alba ‘Caerulea’) is famous for its use in cricket bats, as it is robust and lightweight, it may also be used in furniture. It is also popular in short cycle (SRC) producing malleable strands for baskets ( such as the traditional Sussex Trug), matts or light fences or structures.

[edit] Beech coppice

Beech trees (Fagus sylvatica and grandifolia) can be pollarded or coppiced, the wood being used in the manufacture of furniture as well as flooring, veneers, boatbuilding, cabinets, plywoods and musical instruments. Beech is a hard and strong wood but cannot withstand moisture, so not durable externally and mostly used for interiors. In the UK, traditionally the bodgers of the Chilterns pollarded green wood beech, using the craft of wood turning on site to form slim furniture legs which were then sold to the local furniture manufacturers in the area.

[edit] Sweet Chestnut coppice

Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa) is a popular coppice and pollard species in the south of England, which it is thought was introduced by the Romans, it contains high levels of Tannic acid making it a strong durable hardwood, which also produces edible nuts. Traditionally these forests were regularly managed, with some larger oaks that could be harvested on longer rotations. Many of these forests are now over mature (overstood), no longer actively managed and used mainly for recreation. However, because of the strength and durability of sweet chestnut as a modern building material, well as the environmental benefits, there has been somewhat of a resurgence of coppicing this timber, using modern finger jointing techniques to produce long regular external timber cladding boards at scale.

[edit] Oak coppice

Oak trees (Quercus) have a great many uses, as the wood with its high levels of tannic acid is a very durable wood, some of these may be applicable to pollarding, though in most cases it is a standard forestry product with harvest cycles well over 10 years, and so not considered Rapidly Renewable. However it can be pollarded and coppiced as a way to harvest smaller parts on shorter cycles for fence posts, railroad ties or floors as well as elements of furniture and interiors. Longer harvest cycles well over 10 years produce larger timbers which have been used for many years green (not dried), for traditional Oak frame structures, using joints and pegs, sometimes called traditional green oak framed buildings.

Other species known to be suitable for this pollard management are Maples (Acer), Black locust or false acacia (Robinia pseudoacacia), Hornbeams (Carpinus), Lindens and limes (Tilia) as well as Planes (Platanus), Horse chestnuts (Aesculus), Mulberries (Morus), Eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis) Yews (Taxus) and even Moringa trees.

Other species known to be used in coppicing include Ash (Fraxinus), Alder, Black Locust, Elm (Ulmus), Redbud (Cercis), Sycamore (Platanus) and Tulip tree (Liriodendron).

[edit] Bamboo coppice

Within the Bamboo (Bambusoideae) family there are some 116 genera and over 1400 different documented species that grow all over the world, many of which are suitable for construction and use in furniture. Bamboo is the fastest-growing plant on earth and can produce large enough to be used structurally, some plants can grow at a rate of 0.00003 km/h and the Chinese moso bamboo can grow almost a metre in a single day. Although one might not associate bamboo directly with the traditions of coppicing or pollarding, it is managed in a very similar way either by cutting at the base to produce long poles or topped for smaller products.

Bamboo shoots are connected to their parent plant by an underground stem, called a rhizome, so the shoot doesn’t need leaves of its own, until it reaches full height. Unlike timber, bamboo doesn't grow in rings that thicken the stalk of a tree, so it is some ways more efficient, growing straight up as a single stick, meaning it can produce perfectly round quite thick diameters in very straight sections. Some examples of bamboo used in construction are listed but there are many more;

- Common bamboo (Bambusa vulgaris)

- Giant stripy bamboo (Gigantochloa verticillata)

- Giant thorny bamboo (Bambusa bambos)

- Giant timber bamboo (Bambusa oldhamii)

- Golden bamboo (Phyllostachys aurea)

- Balcooa bamboo (Bambusa balcooa

- Big jute bamboo (Dendrocalamus latiflorus)

It has a traditionally been used in construction for centuries and is still used to create construction scaffold towers for buildings. Today is is also processed to make board, flooring and cabinet making materials it is a durable hard wearing material that is increasingly being used as a replacement for slower growing timber products.

[edit] Forestry crops bark

The bark of a tree is the outer layer that protects it from the weather and drought, insects and animals, bacteria and fungi as well as natural disasters such as fire. The characteristics of bark vary dramatically with species, from its thickness to its properties but essentially consists of the periderm, made up of cork (phellem or suber), incl the rhytidome, cork cambium (phellogen) and phelloderm, each element has different qualities. Some species of tree accrue specific substances in their bark which are good for making spices, sunblock and insect repellent, whilst the inner bark is a resource for resins, tannins, and even the precursors to products such as latex gloves.

In agriculture, there is a technique called girdling where the part of the bark is stripped below ripening fruit to allow sugars to remain concentrated in the fruit, and gives a better harvest. Girdling is also used to describe the process of removing a complete ring of bark from a part of a tree which over time will kill that part of the tree. The term might also describe the process of removing the entire bark from a tree in cork harvesting though not normally, as the trees in this process can withstand losing their bark and it is repeated every few years.

[edit] Cork oak

The best-known bark is that which is harvested from the cork oak (Quercus suber), it is harvested for its thick soft spongy phellem to produce what we commonly know as cork, used in the wine and construction industries. Once a tree is about 25 years old it can be harvested for its virgin cork and then every 9 years, after 38 years the third harvest, the tree produces the highest quality cork. The harvest quantity is determined by height and diameter, 1 metre in diameter by 3 metres in height for example. The Cork Oak lives for about 150 - 200 years on average meaning that it will be harvested about 15 times over its lifecycle. However, cork has increasingly been used for a variety of other applications such as insulation and flooring.

[edit] Birch bark

The birch tree (Betulais) is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams, closely related to the beech-oak family Fagaceae. Elements of the bark of the Beech tree have for many years been used for medicinal and health purposes, but also the outermost layer was used in roofing because it is thin and resistant to water. Tree bark might also be cut into single pieces to use as shingles for external walls or as a roofing finish. The inner spongy part of the bark has surprisingly also been used as a foodstuff to add to flour, bread and cereal.

[edit] Forestry crops tapping

Tree tapping is a process that has been carried out for centuries, it is probably most famous for rubber and maple syrup but may other trees can also be tapped such as the palm tree, birch tree as well as poplar, elm, sycamore, alder, and walnut to name a few. The process involved making a small cut in the bark of the tree and inserting a funnel of some kind to draw of the natural sap of the tree, specific details vary from species to species but the principle is the same and when carried out correctly does not permanently harm the tree.

[edit] Rubber tapping

The rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis), is a tropical tree of the spurge family (Euphorbiaceae). It is cultivated in the tropics and subtropics and replaced the rubber plant in the early 20th century as the main source of natural rubber. It has a softwood, a large area of bark, and grows quite tall. There is a milky liquid called latex that will drip from a cut in the tree bark this liquid contains about 30 percent rubber, which can be coagulated and processed into solid products, such as tyres. Latex can also be used in a concentrated form to produce dipped rubber good, such as gloves.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Chain of custody.

- Confederation of Timber Industries.

- Deforestation.

- Delivering sustainable low energy housing with softwood timber frame.

- Environmental plan.

- European Union Timber Regulation.

- Forests.

- Forest ownership.

- Forest Stewardship Council.

- Legal and sustainable timber.

- Legally harvested and traded timber.

- Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification.

- Sustainability.

- Sustainable materials.

- Sustainable timber.

- Sustainably procuring tropical hardwood.

- Timber.

- Whole life carbon assessment of timber

Featured articles and news

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.

Heritage staff wellbeing at work survey.

A five minute introduction.

50th Golden anniversary ECA Edmundson apprentice award

Showcasing the very best electrotechnical and engineering services for half a century.

Welsh government consults on HRBs and reg changes

Seeking feedback on a new regulatory regime and a broad range of issues.

CIOB Client Guide (2nd edition) March 2025

Free download covering statutory dutyholder roles under the Building Safety Act and much more.

Minister quizzed, as responsibility transfers to MHCLG and BSR publishes new building control guidance.

UK environmental regulations reform 2025

Amid wider new approaches to ensure regulators and regulation support growth.

BSRIA Statutory Compliance Inspection Checklist

BG80/2025 now significantly updated to include requirements related to important changes in legislation.

Comments

[edit] To make a comment about this article, click 'Add a comment' above. Separate your comments from any existing comments by inserting a horizontal line.