Checking and approval in design - a quality management perspective

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Procedures for control of design and construction must have originated in early history. The Great Pyramid of Giza, Egypt is famous for the accuracy of the geometry for a structure that measured 146.5 metres high with a base of 230.4 metres square, eg the four sides of the base of the Great Pyramid of Giza have an average error of only 58 millimeters in length – from Cole Survey (1925) based on side lengths 230.252m, 230.454m, 230.391m, 230.357m [1].

How the Pyramids of Giza were built is unknown. Nevertheless, it can be concluded that, to achieve great accuracy, the design and construction techniques used must have included elements of quality control (checking and approval) and quality assurance (technical review).

Today, for design projects and associated professional studies work, the most important quality control techniques are checking and approval of the deliverables. However, this article will widen the topic to include technical review (aka Design Review) as a similar, necessary step en route to verification that deliverables meet the contractually specified requirements. Review can be used to drive out defects earlier in the project, well in advance of final submission, and can therefore be regarded as a quality assurance (QA) activity rather than a quality control one.

ISO 9001:2015 – Quality management systems – Requirements [2], sets out in ‘chapter 8 – Operation’ its expectations for review and verification (checking).

[edit] Why Check and Approve?

It is in the interests of both Designer and Client to know that the requirements in the contract have been achieved, as well as ISO 9001 [2] requirements if the Designer is certified to that standard. In this regard, checking and approval is a tool used by the Designer to mitigate its risk of inadequate work. It is also a technique expected by its Professional Indemnity (PI) insurers who want to limit their exposure.

Checking is scrutiny by the Designer of all the deliverables to be issued to assess their suitability to address the requirements set out in the contract. Deliverables can be made up of documents (eg reports), drawings, calculations, 3D design model outputs and other computer model outputs.

Checking needs to be planned to ensure it is comprehensive and effective, particularly on complex schemes.

[edit] Planning for Checking and Approval

Checking of deliverables can be an iterative process, either within a discipline or across more than one discipline during project development, but formal confirmation is required at key stages.

Planning for checking and approval should be done in the Quality Plan or, alternatively, Execution Plan. This is known as the ’Scope of checking’; it comprises four aspects:

|

WHEN to undertake a check? WHAT level of check is required? WHO is responsible for the check? HOW the checking should be carried out. |

These elements are considered separately below.

[edit] WHEN to undertake a check?

Identify at what milestones in the design process checking is required, eg at design freeze where design is halted to take stock. This is particularly appropriate with Building Information Modelling (BIM) where model development passes through a series of stages, eg ‘Work-In-Progress’, ‘Shared’ (Internal) and ‘Published’ (External) recognised by formal issues of deliverables.

Planning for the checking of the work of Subconsultants needs to be considered. The contract should require confirmation that the Subcontractor has verified that their own work meets requirements before submission. Furthermore, Client or stakeholder involvement in the review process needs to be scheduled as it can otherwise introduce delay.

It needs to be recognised that incoming information (eg documents, drawings, standards, etc) from other parties must be checked to show that they are appropriate to use.

[edit] WHAT level of check is required?

The level of check for documents, drawings, calculations and models is usually defined by each organisation in its checking procedure.For calculations, levels of checking graduate from ‘Self-check’ through to arrangements for assessing critical design calculations.Drawing and document checking levels can follow a similar methodology.

Procedures such as QA BIM workflows should be coordinated across parties (Consultant, Employer, Subconsultants, etc) to ensure consistency in the processes across the project

The sophistication of modelling levels of checking needs to be appropriate to the stages of development, eg issues can be made within the different stages bearing ‘Suitability codes’ to set out the phase of progress.

[edit] WHO is responsible for the check?

It needs to be shown that checkers and approvers are competent for their roles. This may take the form of an authority matrix showing the checkers and approvers for each discipline and the topics for which they are competent to check and/or approve. The matrix can be an output of the company’s professional development process. It should form part of project planning, eg be referenced in the quality plan.

For more complex projects, it may be that more than one checker is required to cover the skillsets of competencies required or, indeed, to make best use of people resources, eg for calculations an experienced specialist would check the principle, method assumptions and design criteria whilst a more junior person may carry out the arithmetical check.

Ideally, the author, checker and approver should be different people. The author must not check their own work as part of the checker's purpose is to bring a fresh pair of eyes. Also, it is recommended that the checker and approver of a deliverable should not be the same person unless the work is being done by a small team and a second person with the necessary competencies is not available; this should be recorded in the quality plan.

[edit] HOW the checking should be carried out.

This is addressed for all types of deliverables in section 4 – Checking, immediately below.

[edit] Checking

[edit] Overview of the approach to checking

Those who prepare deliverables should always check their own work before submitting it for the planned checking and approval.

No deliverable in any state of completion should be issued without undergoing a level of checking; this includes 'Draft for Comment' submissions. The recipient (Client) wishes to analyse and indeed may seek to rely on the document or drawing and will not check its accuracy or reliability for you. In the author’s auditing experience, it can happen with 'Draft for Comment' documents that the Client's only comment is, 'That's great, treat the document as first issue', in which case, without checking, there would be an issued document that hasn’t been verified by its originator.

In addition to completeness and accuracy of the deliverable, checkers could be looking for additional items such as:

- The relevant codes and standards have been applied and regulatory requirements met;

- The actual buildability / constructability of the design;

- Interface matters such as inter-changeability of components and inter-operability with other systems;

- Maintainability, eg the ease of changing a component after construction, thus achieving future proofing for a 25 years maintenance contract;

- Whether necessary approvals have been obtained, eg heritage consent for a listed building, and permissions from industry regulators;

- Risks to the project have been assessed and mitigated, eg personal health and safety, safety of the design and environmental impacts such as contaminated land;

- Opportunities for the project to maximise its benefits to the Client, operators, users etc have been evaluated, eg sustainability opportunities.

- Any contract or design change approved by the Client has been considered.

This must also be defined in the ‘Scope of Checking’ within the quality plan.

Records of checking need to be kept (eg marked-up check copy of a document or drawing, either in manuscript or electronically using the tracked changes function in software such as ‘MS Word’). This is to provide evidence of the veracity of the check, ie that the planned checking was carried out systematically. Similarly, calculations sheets and model run checking data, together with their associated cover sheets, are also required for future reference. As an extra step to preserve checking records of documents, a pdf copy of the comments may be made.

A record copy of the ultimate issue of any version of a deliverable is also essential. It should bear the signatures of the author, checker and approver, and date of check, either in manuscript or by electronic ‘Workflow’.

Electronic document and drawing management systems (EDMS) can have 'Workflow' functions that can be used to record authorisations for checking and approval of deliverables by the nominated people. Some 'Workflows' can also automatically retain the associated check and record copies as evidence of fulfilment of the process. There will be an audit trail of the checking and approval in the version history of the document or drawing in the system.

When wet signatures are in use, as a control the Authority Matrix should contain the signatures of the checkers and approvers to enable a comparison with signatures shown on the cover sheet of a document or drawing.

[edit] Documents

‘Documents’ can include:

- Reports

- Specifications, Procedures, Datasheets

- Tender documents

- Technical notes

- Spreadsheets

- Databases

- Presentations

- Or, indeed, any written description, account or opinion given after investigation or consideration

Besides being checked for the accuracy of their technical content, documents are typically checked for use of the correct template, proof-read for grammar and spelling and subject to an assessment of consistency with other work.

An area for focus relates to including calculations in the report as it needs to be checked that the output from the calculations has been transferred correctly to the report.

[edit] Drawings - (2D)

A fundamental check is for standardisation, eg to ascertain that all drawings are drafted in the template agreed with the Client.

As with documents, a check for consistency with other work is important here, eg between reinforcement drawings and general arrangement drawings.

A colour-coded, annotation method is often used by the checker on hard copy drawings, eg as follows:

| A colour-coded annotation example: | |

| Yellow | Correct |

| Red | Incorrect – cross-out or circle incorrect work and note corrections in manuscript; |

| Green | Correction made by draughter; |

| Blue | Correction verified by checker |

It can also be used in EDMS using electronic red-lining tools which then save to a dedicated file.

As an example, bar schedules need to be checked to ensure that the reinforcement shown on associated drawings has been properly carried forward to the schedules. Checkers should consider whether diameters, numbers, dimensional details and any summaries of lengths are correct.

A question that sometimes comes from someone producing a sketch, not a full drawing, is whether they need to have it formally checked and approved. The answer is yes, if information put forward in a report containing the sketch relies on any part of that sketch. The use of suitability codes in an electronic workflow would indicate the level of confidence in a sketch.

[edit] Calculations

Calculations are prepared, not only to satisfy the Designer of the accuracy of the design, but also as a permanent record of the design decisions made and the criteria used which contribute to shaping the design output.

For each set of calculations, the checker should consider the following:

- Is the purpose clear and specific?

- Are the assumptions made clearly set out?

- Are the parameters and formulae used recorded?

- Were the applicable codes and standards referenced?

- What was the software used and its version status?

- Was the software validated for the type of calculation?

- Was the input data checked?

- Is the output definitive, eg pass / fail?

Structures such as bridges have their own industry-specific requirements for checking. In this case, there are different categories (CAT) of checking:

| Categories of design checking: | |

| CAT I | For simple designs - by another person within the design team; |

| CAT II | For more complex or involved designs - by another person in the company not involved in the design or consulted on it; |

| CAT III | For complex or innovative designs - by people in another company fully independent of the originators and without reference to their calculations. |

CAT III checking, when found satisfactory, is followed by the issue of a CAT III check certificate, eg a bridge design which is submitted by the Designer and counter-signed by the Client.

Some projects require the Designer to similarly produce a design certificate to certify that design is in accordance with standards, works information etc, and has been checked and approved.

[edit] Building Information Modelling (BIM) - (3D+)

BIM takes place in a common data environment (CDE) meaning that a standardised approach to the management of drawings and calculations is required to ensure compatibility of the information across the different disciplines involved. This facilitates collaborative working in the production of models. The standards that enable this include ISO 19650-1:2018 – Organization and digitization of information about buildings and civil engineering works, including BIM – Information management using BIM – Part 1: Concepts and principles [3], ISO 19650-2:2018 – Part 2: Delivery phase of the assets [4] and the PAS 1192 series framework.

The ‘Scope of checking’ for BIM work should be planned in the quality plan or BIM execution plan (BEP), as with the general approach in section 4a). In addition, the proposed software packages to be used by each discipline should be identified therein, including model check and review software.

In broad terms, a check is required when:

- Model information is transferred from one format to another, (eg between software packages) – a model integrity check;

- Model information is exchanged between one party and another for a defined purpose (eg internal coordination, external collaboration or final submission).

ISO 19650-1 [3] article 12 recognises three states of model development within which this checking is required:

- Work-In-Progress (WIP) – development by the task team;

- Shared - suitable for collaboration;

- Published - ready to be issued to the Client.

For each of these states, ‘Suitability codes’ are used within to designate the level of confidence in the deliverable, eg ‘S1’ -Suitable for coordination (models only) and ‘S3’ – Suitable for review and comment. The level of checking required for each suitability level within each stage becomes more detailed as model development advances towards production of the construction information. The ‘Scope of checking’ in the quality plan should reflect this.

3D models can be defined as one of three types:

- Design (Authoring) model, ie a 3D graphical representation of drawings;

- Analytical model - used for engineering analysis and design, ie a 3D representation of engineering calculations and analysis.

- Federated model – a combined, linked model of distinct discipline models used for coordination and collaboration.

Transactions between design and analytical models during design iterations require checking to ensure critical embedded information with the model is retained and the transferred geometry is correct.

The federated model is subject to multi-discipline design reviews, assessment of the coordination between disciplines and clash detection which looks at where there is conflict between the underlying models.

At the ‘Publish’ state, the contracted deliverables which will require checking are typically documentation that has been output from the BIM model, eg 2D drawings, 3D renditions, schedules etc. Also, the actual 3D model, as a deliverable, will be checked.

These checks and reviews are captured, eg in clash detection reports or model validation checklists.

An important consideration is providing training to ensure that the project team can use the digital tools for checking and approval. The change to reviewing 3D models (for engineers used to working in 2D) and the different possible methods used to capture the checking of a 3D model (excel checklist, 2D extractions, 3D screenshots etc) need to be appreciated.

Types of BIM check:

- Self-check - checking of BIM modelling begins with the computer aided design (CAD) technician taking responsibility for self-checking their work;

- Discipline check – that what is drawn is what was asked;

- Quality assurance – checking of the model set-up, eg to confirm compliance with CAD / BIM standards to enable collaboration;

- Model content – a check of the formatting of the information in the model, eg BIM output must reflect the native model it has been exported from and that BIM output meets agreed data exchange formats – and completeness of the data being presented;

- Technical (engineering) – this is a discipline-specific design check of engineering standards, eg for fire escape routes, that may look at 3D model rendition, 2D extractions and documentation such as specification, schedules and quantity take-offs;

- Coordination – also known as clash detection, a software tool is used to identify conflict between the component models – also through interdisciplinary coordination meetings where the more ‘engineering’ related clashes between disciplines get resolved.

Further detail, eg re responsibilities, can be found in ISO19650-2 [4] articles 5.6 and 5.7.

[edit] Computer modelling and demand forecasting

Generally, the modelling or forecasting checker makes the same considerations as for calculations (see para 4c), eg checking input data and output results from the model. Additionally, the checker must be satisfied of the reliable functioning of the model.

Early consideration should be given to:

- Is the software approved for use?

- Has the software been verified for use in this application?

- Are known issues with the software accounted for?

- Is it appropriate - is the computer program suitable for what you are trying to get out of it?

- Is training required to use the software?

- Have there been any modifications to the software or any relevant parameterisation?

- Have there been any drifts in the software that has taken it out of calibration?

Note: Software is considered to be any electronic system that is using code as an application for, in this instance, computer modelling and/or demand forecasting.

Fundamentally, there are three elements where checking is necessary:

| Computer modelling & demand forecasting checking overview: | |

| Dedicated Quality Plan | Producing a dedicated quality plan to formalise the approach to modelling and checking, including planning the ‘Scope of checking’ and nominating competent people for the roles |

| Early peer assist | Early intervention is recommended in the form of a peer assist between the modellers and an experienced colleague which can be beneficial in setting the direction for the development of the model and planning its quality assurance |

| Checking according to plan | Demonstrating that checking is taking place in accordance with the quality plan, eg review of checking records. |

[edit] Checklists

Use of checklists for checking and approval is most suitable where the repeatability of the check by discipline is important and/or where the team is less experienced, as it can provide a template for the check. However, it is still important to encourage wider thinking, not bounded by a checklist.

Engineering discipline checklists can include, for example, bridges, light rapid transit (LRT), building structures, transport planning and water. They can be made bespoke for drawings, calculations and modelling.

Further information is available by reading the Quality Checklist article.

[edit] Approval

Approval is not a second full check. The approver is looking in overview and satisfying themselves that an effective check has been done. This may be done in many ways, eg carrying out a sample check, focusing on checking key features of the deliverable and/or making comparison with known reference sources or previous project experience.

An approver must satisfy themselves that:

- The checkers involved were competent, as nominated in the ‘Scope of checking’ section of the quality plan;

- The check generally followed the plan in that ‘Scope of checking’;

- Findings from technical reviews have been addressed;

- Risk assessments are detailed, eg for mitigating issues related to the safety of the design and its environmental impacts;

- Customer requirements within the contract have been met.

Thereby the approver is ensuring that the collected information to be submitted, comprising the design or professional study, has been compiled with ‘Reasonable skill and care’.

[edit] Review (technical or design)

Checking and approval is primarily a quality control technique, ie used when the production of deliverables is advanced, whereas its associated quality assurance method, Review, can be used earlier to influence the development of those deliverables. For instance, a series of single discipline reviews (SDR) may precede an inter-disciplinary review (IDR) before final submission with levels of checking taking place of the inputs to each stage.

Review should also be planned in the quality plan, again following the principles of ‘Scope of checking’ by identifying, ‘When, What, Who, How’. By way of competency, the nominated reviewer must have expertise in the technical areas under review. They should preferably be independent of the project team to bring that ‘Fresh pair of eyes’.

The reviewer is ascertaining whether the work being developed is consistent with the objectives established for the project and may refer to all project records such as documents, drawings and calculations.

They will also consider whether opportunities for the project to maximise its benefits to the Client, operators, users etc have been evaluated, eg sustainability opportunities.

[edit] Collaborative working and ‘Progressive assurance’

Collaborative working with the Client and other project partners is increasingly important on major projects whether or not it involves BIM. The Client and even Contractors can see the benefits of being involved earlier in the project to shape its direction, either as contributors or reviewers. ISO 44001:2017 – Collaborative business relationship management systems – Requirements and framework [5] applies.

In this culture of change the consultant is still, rightly expected to take responsibility for assuring its deliverables, ie producing accurate reports, drawings etc, and thus needs to plan the process of checking and approval and review throughout project development in its ‘Scope of checking’. This approach is also known as ‘Progressive assurance’.

During collaborative working, and not just during checking and approval, contributions from a range of people with a variety of expertise can lead to the generation of ‘Lessons learned’ and even innovation ideas. For instance, the audit trail from minutes of IDR meetings is a rich source of information. Increasingly, a company needs a knowledge management system to capture these, particularly for future projects.

[edit] Auditing

Here, auditing is a review of the effectiveness of the management system and, on a project, should always consider whether arrangements for checking and approval and review are planned and implemented.

Auditing should be conducted in line with ISO 19011:2018 – Guidelines for auditing management systems [6].

[edit] Conclusion

Checking and approval can be a wide-ranging technique. It is used to assess information which is shared with collaborators or published by way of issue to the Client. This covers deliverables from reports to drawings, calculations and BIM outputs.

The planning and execution of checking and approval is built around the ‘Scope of checking’ identified in the quality plan at the start of the project. It has four aspects:

- WHEN to undertake a check?

- WHAT level of check is required?

- WHO is responsible for the check?

- HOW the checking should be carried out.

The competency of the checkers and approvers in the disciplines in question must be demonstrated eg in the company’s professional development process.

Supporting evidence such as check and record copies of deliverables are needed to show that the planned arrangements for checking were implemented.

Checking and approval is best aligned with review (technical or design). The resulting findings from both approaches can provide an opportunity to learn lessons for the current and future projects, particularly where a collaborative approach with others is adopted.

In a culture of collaboration that can promote change from an early stage, the consultant is still, rightly expected to take responsibility for assuring its deliverables, and thus needs to plan the process of checking and approval and review throughout project development in its ‘Scope of checking’. This approach is also known as ‘Progressive assurance’.

[edit] Sources:

- [1] Wikipedia - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Pyramid_of_Giza.

- [2] ISO 9001:2015 – Quality management systems – Requirements.

- [3] ISO 19650-1:2018 – Organization and digitization of information about buildings and civil engineering works, including BIM – Information management using BIM – Part 1: Concepts and principles.

- [4] ISO 19650-2:2018 – Part 2: Delivery phase of the assets.

- [5] ISO 44001:2017 – Collaborative business relationship management systems – Requirements and framework.

- [6] ISO 19011:2018 – Guidelines for auditing management systems.

Rev 1.0 (15/8/2020): Original article written by Kevin Rogers & reviewed by Tony Hoyle and Keith Hamlyn on behalf of the Construction Special Interest (ConSIG) Comptency Working Group (CWG). Article peer reviewed by the CWG and accepted for publication by the ConSIG Steering Committee.

--ConSIG CWG 16:09, 17 Aug 2020 (BST)

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Change control: a quality perspective.

- Collaboration: a quality management perspective.

- Design freeze: a quality perspective.

- Design: a quality management perspective.

- Digital quality management in construction.

- Quality checklist.

- Quality culture and behaviours.

- Quality management systems (QMS) - beyond the documentation.

- Quality manuals and quality plans.

- Quality tools: fishbone diagram.

- Stakeholder management: a quality perspective.

- Quality.

Featured articles and news

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

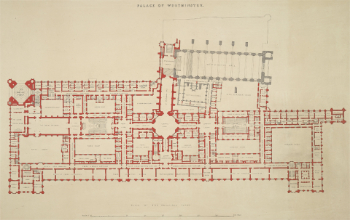

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.

The first line of defence against rain, wind and snow.

Building Safety recap January, 2026

What we missed at the end of last year, and at the start of this...

National Apprenticeship Week 2026, 9-15 Feb

Shining a light on the positive impacts for businesses, their apprentices and the wider economy alike.

Applications and benefits of acoustic flooring

From commercial to retail.

From solid to sprung and ribbed to raised.

Strengthening industry collaboration in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Institute of Construction and The Chartered Institute of Building sign Memorandum of Understanding.

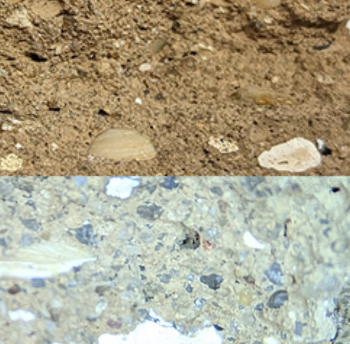

A detailed description from the experts at Cornish Lime.

IHBC planning for growth with corporate plan development

Grow with the Institute by volunteering and CP25 consultation.

Connecting ambition and action for designers and specifiers.

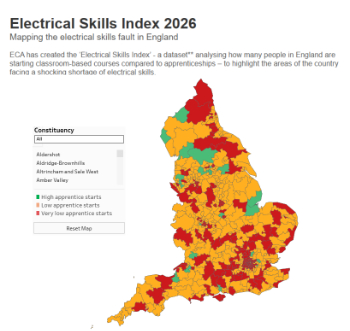

Electrical skills gap deepens as apprenticeship starts fall despite surging demand says ECA.

Built environment bodies deepen joint action on EDI

B.E.Inclusive initiative agree next phase of joint equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) action plan.

Recognising culture as key to sustainable economic growth

Creative UK Provocation paper: Culture as Growth Infrastructure.