Successful Audits - Techniques for Everyone

[edit] Summary

People can have preconceived ideas about audits often thinking of them as something to be avoided at all costs. However, auditing, if it is done correctly, is actually a very powerful and useful tool to help any organisation. It can do this in several ways which includes:

- Helping us to perceive potential risk to a particular aspect of our organisation to ensure we are delivering correctly potentially preventing costly mistakes. If it does identify things are not quite right, we can correct them.

- Challenging us to review our day to day working practices and make sure we are following our management systems – or, if we are not, examine why not. This might mean we then update what we are doing or alternatively change what is documented because that was not the best way to do it.

- Providing a structured and robust mechanism to demonstrate compliance. This can be internal audits demonstrating compliance to clients or management, audits which assess performance of our suppliers, or audits conducted by Certification Bodies which enable us (by showing we are compliant to specified standards) to obtain our ISO certifications, for example.

- Enabling us to identify best practice in a safe environment. This can then be shared with others.

- Providing a platform for training in receiving an external audit and thereby turning something that is potentially uncomfortable into a routine activity

Audits should therefore be seen as something positive – a way to help us both improve but primarily provide confidence (i.e., 'assurance') things are right.

This article could have been entitled, “How to Survive an Audit”. It emphasises the need for serious preparation to make sure that you have a robust management system that meets the needs of your business, identifies, assesses and controls the risks to the business and meets the requirements of the standard. It discusses what you can expect from an auditor before during and after an audit and what you can do to make the audit a success.

This article discusses how auditors prepare, conduct and follow-up audits as seen from the auditee’s perspective. It provides an insight into the audit process so that all parties can show success at the end of the audit.

It is based on the standard techniques that are derived from ISO 19011:2018, “Guidelines for auditing management systems”. This specification has a much wider brief, as it provides guidance on all aspects of auditing and is the basis upon which Certification Bodies are judged. However, the following paragraphs cover only part of the Guidance.

By the way, auditors may find this article useful also!

[edit] Introduction

An audit is “a systematic, independent and documented process for obtaining audit evidence and evaluating objectively to determine the extent to which audit criteria are fulfilled” (ISO 9000). The audit criteria can be an international standard, a local procedure or any other definitive document that contains requirements that are to be met by the organisation being audited.

There are six principles for auditing:

- Integrity. The auditor must be beyond reproach in all dealings with the organisation being audited.

- Fair Presentation. All findings must be presented without favour or bias.

- Due Professional Care. The auditor is a professional and must behave as such.

- Confidentiality. The outcome of an audit, together with everything that is seen or heard must not to be discussed outside the organisation being audited, and the auditor’s management. They belong to the organisation being audited.

- Independence. The auditor should not, where practicable, audit an organisation (or element of an organisation, in the case of an internal audit) of which s/he is a part.

- Evidence-Based Approach. The auditor is a seeker of facts. All findings must be factual and based on observed evidence.

These principles should:

- Help make the audit an effective and reliable tool in support of management policies and controls

- Provide audit conclusions that are relevant and sufficient

- Enable Auditors with similar levels of auditing experience and technical background. working independently of each other, to reach similar conclusions in similar circumstances

An audit requires careful investigation and meticulous planning before the day of the audit itself. The auditor should try to gain as much relevant information about the auditee (the organisation that is being audited) as practicable. Once sufficient information has been gathered, the auditor can prepare a programme for the day, together with the arrangements needed to be made to travel to the auditee’s premises and so forth. An opening meeting is held at the start of the audit before the auditor sets out to conduct interviews and review evidence of the way the organisation is operating. As part of this, the auditor should consider the relevance of the controls as well as the level of conformance to a standard. The audit ends with the auditor presenting the findings of the audit and confirming agreement with any conclusions that have been drawn. The auditee provides the auditor with confirmation that any findings have been addressed properly. The auditor finally reviews the actions, either remotely or on site, and closes the audit, setting a date for the next one if appropriate.

[edit] Types of audits

There are three types of audits, as follows:

[edit] First party audit

A first party audit, often called an internal audit, is conducted by persons from the same organisation, but who are independent of the part of the operation being audited. Much of the guidance that is given below will be relevant, although familiarity may shorten things down. For example, an opening meeting may be a simple short affair, as all parties understand what is to happen.

[edit] Second party audit

A second party audit is conducted by a purchaser on a supplier. These can be the most difficult to manage, as there are frequently undercurrents of which the auditor must be aware. For example, the supplier may be bidding for work and may try to influence the auditor openly or maybe not so openly. There is also a potential for a project manager or procurement department of the organisation requesting the audit to put pressure on the auditor to compromise the audit to bring about a preferred outcome. The auditor must take a great deal of care to remain independent and recognise that the only objective is to provide an accurate and distanced honest view of the auditee’s operation.

[edit] Third party audit

Third party audits are conducted by independent auditing organizations, such as regulators or those providing certification. The auditor in this case will follow the protocols that are laid down in ISO 19001 and will be totally independent of the organisation – and of any organisation that has provided consultancy into the organisation. Note that this latter statement precludes organisations that will sell an organisation certification based on a consultancy visit and an audit, possibly in the same week.

[edit] Accreditation of certification bodies

The use of an accredited certification body is recognised as best practice as all certification bodies are assessed against the same standards to ensure that certification bodies are impartial, auditors are competent and that they provide a consistent service.

UKAS is the only accreditation body for the UK. It monitors the arrangements, processes and delivery of certification bodies, so they are also subject to surveillance.

UKAS is a private, not for profit organisation which operates under a Memorandum of Understanding with the Government, through the Secretary of State for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS). It has been formally appointed in its role as the UK’s sole national accreditation body through the Accreditation Regulations 2009 (S.I. No 3155/2009) and the Product Safety and Metrology etc. (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 (S.I. 2019/696) (as amended). Further information on UKAS’ role with Government and the benefits it provides is available here. (Source UKAS FAQS on https://www.ukas.com/faqs/)

It should be recognised that other Accreditation Bodies exist that may have accredited registration bodies, especially outside the United Kingdom. Care should be taken to confirm that any Accreditation Body is a member of the International Accreditation Forum or equivalent.

In passing, there are certification bodies who are operating outside the cover of formal accreditation and who offer a cheap path to registration. Organisations should take care and consider whether they are getting value for their money.

[edit] Vertical versus horizontal audits

[edit] Vertical audits

These audits would be undertaking by following a process by discipline or function. For example, a vertical design audit would look at the following for a design department:

- Requirements capture

- Feasibility

- Conceptual design

- Detailed design

- Buildability or manufacturability.

[edit] Horizontal audits

These audits can be used to assess the effectiveness of a process across functions/departments or lifecycle. They follow an audit trail that follows the process for goods and materials, for example:

- Purchasing

- Goods receiving

- Stores and Materials Handling

- Stores records

- Material Requisition

- Material Issue

[edit] Overview of the audit process

Auditors are expected to carry out audits in two phases:

- Phase One: a review of the documented management system to make certain that there is a good chance that the rest of the audit is successful

- Phase Two: Execution of the audit itself.

The first phase is straight-forward if the documented system is in a transferable form, i.e., hard copy or .pdf. A copy can be offered for review. It’s more difficult if the system is interactive and sits on a server, although authorisation can be given as auditors are trustworthy.

The auditor uses this review and a possible initial visit to become familiar with the organisation and how it works. This will form the basis for the audit plan and checklists of questions. At this point, a decision will be made based on conformance to a standard and/or a set of contract requirements to either continue to Phase Two or to ask for further information. It could also result in the audit not taking place.

In the second phase, the auditor attends the organisation, conducts an opening meeting to explain how the audit will be conducted, undertakes the audit by asking pertinent questions and revieing evidence and close the audit by presenting a report verbally at the closing meeting and with a written report at a suitable time.

The auditee is responsible for taking action to resolve any issues found. These may be reviewed later, possibly at the next scheduled audit.

This process is described in more detail below.

[edit] Auditor preparation (phase one)

[edit] Reviewing the management system

It is vital that time is spent going over the management system to make sure that it meets the operational needs of the organisation as well as the relevant specification, such as ISO 9001. The central question is this:

“Does the management system address all the risks that have been identified arising from all known sources?”

The auditor will want to see how you have identified any impacts, good or bad, that can arise and to see that the risks they create have been assessed. Where necessary, the management system should aim to reduce these to as low as reasonably practicable. Obviously, all the requirements of the standard must be met!

The auditor will try to gain as much information as possible before the audit. The minimum of information the auditee should provide for review is a copy of the defined management system.

The amount of information the auditor will need will depend on the audit being conducted. For example, a first party audit of a department will only need the procedures relevant to that department. On the other hand, a Third-Party auditor may need to see only the top-level documentation that covers the whole scope of the audit. (The scope of the audit may not be the whole organisation!) The information suggested for a Second Party auditor is more circumspect, as it will depend on the purpose of the audit. For example, it could be the same as for a Third-Party audit or it could be the Quality Plan and/or the main supporting procedures for the area that will be audited.

This can be difficult if the auditee has decided, like many these days, to hold the system on-line. There may be protocols that prevent the auditor from accessing the management system from outside the organisation. A discussion with the auditee’s management may help the auditor to prevail. However, it is early in the relationship which may make things less easy. Frequently, organisations create a Quality Management System hard-copy document for issue to external auditors. Of course, this problem doesn’t happen for First Party audits.

The external auditor should see whether the defined management system talks to how the organisation works or is simply the standard turned back, for example, if the standard says, “do this”, the management system says, “we do this”. This is not helpful to the auditor and should be avoided. In developing the Quality Management system, the organisation should seek to end up with processes/documents that describe the way it works. They should be used by the organisation to run the business.

In a First Party, it is assumed that the organisation has assured its Quality Management System so that the auditor does not have to go back to the fundamentals.

In a little more detail, this is what should be reviewed:

- A copy all or part of the relevant Quality Management System documentation as discussed above. This may mean access electronically, perhaps by download or an attachment to an email. Security of information is paramount, of course.

- An up-to-date copy of the organisation chart if this does not form part of the documentation. Ideally, the main areas of responsibility should be stated.

- A map or plan, defining the areas which are open to audit, those areas which are restricted or where safety precautions are necessary and the location(s) of the places where meetings are to take place.

- The name(s) and title(s) and contact details of the auditee manager(s).

With recent versions of ISO 9001, it is less easy to offer a manual that just reiterates the standard, although there are some “certification bodies” that will do this – avoid at all costs. There is more on this later in the article.

[edit] Pre-audit visit

If time allows, a pre-audit visit is always useful. Frequently, this will be the auditors first visit to the site. It is a great opportunity to make sure that s/he gains a good understanding of the business. The auditor will not be auditing at this time, although impressions from this visit will stick.

It is important to be open in answering any questions, but not to elaborate more than answers the question. As in the audit itself, time is at a premium and the auditor has a considerable amount to get through.

The pre-audit visit can accomplish many things, including

- Getting to create a good working relationship between the auditor and the auditee

- Getting to know the layout of the organisation, both from a management point of view and physically. How long does it take to get to site? How long does it take to walk from one end to the other? What transport has been arranged to move to the work site?

- Getting a first view of the operation, bearing in mind that the audit hasn’t started yet. This should be used as an opportunity for the auditee to demonstrate how the operation works.

- Determining the need for training, PPE, etc., especially where this must be arranged prior to access to the worksite. Any time needed must be added into the programme.

The auditor should write up some notes after the visit for reference during the planning phase. The auditee may also find making a few notes useful!

[edit] Internal audit

The term “Internal Audit” can send a cold chill down the back, but it serves two valuable purposes:

- it provides a chance to confirm the evidence that the management system is working across the business,

- It provides training for auditees.

It is important to have the evidence available – that’s obvious. It is more important to be certain that the auditee can lay hands on it in a reasonable time. So, what counts as “reasonably retrievable”. If the evidence is a form or procedure that is in use day-by-day, it should be immediately to hand. A record that was archived may take longer. Taking this a little further, items that are held electronically can be a problem, unless the auditee knows where the evidence is hidden! A great deal of time can be wasted looking for evidence within complex document management systems.

Obviously, this is an activity that the auditee should carry out prior to the audit. It is not within the job specification for the external auditor.

[edit] Execution (phase two)

[edit] Auditor expectations

On the day of the audit, the auditor will be expecting to enter a business meeting that is broken down into three sections as shown in the Plan for the Day. S/he will understand that there is some nervousness. I recall a CEO trembling during an opening meeting. The auditor will do all possible to create a positive atmosphere in which discussion of the management system can be undertaken in a professional and business-like manner.

Auditors are expected to discuss in an assertive manner, that is, they will tend to lead the conversation without becoming aggressive in any way. Further understanding of the interactions that take place during an audit can be found in the article: “Personal Interaction in Auditing “.

[edit] Plan for the day (audit plan)

The plan for the day should be based around the intelligence obtained from the document review and the pre-audit visit, together with any other relevant information. This could include any contract requirements, especially in second party auditing.

The plan contains the schedule at its heart. There are certain events that form fixed points during the day. These are the opening meeting, the closing meeting, time scheduled for auditors to meet and to write up notes and, of course, lunch. The auditor should be aware of the time throughout the day(s) and adhere to these meeting times. The remainder of the time is spent in interviewing and reviewing evidence. It is advisable not to put fixed times on each interview, as arriving early or late can be an embarrassment as well as potentially losing audit time. For this reason, it is better to state which parts of the organisation will be visited in the morning and which in the afternoon. With staff having full schedules, it is useful to book slots in diaries where necessary – and to work other interviews around them.

[edit] Checklists

So far, the auditor has planned to visit one or more sections of the organisation in sessions before lunch and after lunch. The checklist contains a series of questions that are the “starters for ten”. By reviewing the documentation, the auditor can see a clear “audit trail” through the management system, based on the way it works – not by requirements in a standard. The questions will allow discussion around the matter being audited and, by having a small number of questions, the auditor will be able to adjust the speed of the audit to have a better chance of getting to the various meetings – and lunch – on time. One important point: an auditor should not consider that the impression gained during the review of documentation is necessarily accurate and must be prepared to change direction, whilst maintaining time. Not easy.

An audit checklist:

- Is generated by the auditor

- Provides a structured list of points to evaluate against requirements.

- Identifies and communicates the scope of an audit.

- Is a tool to gather evidence and provide an audit trail.

- Guides the course and controls the pace of an audit.

- Keeps audit relevant to objective.

- Provides evidence of planning

- Assists with note taking.

- Reduces risk to bias.

- Helps to manage time.

- Assists in the preparation of the audit report.

[edit] Conducting the audit

[edit] The opening meeting

This meeting is led by the Lead Auditor if there is a team or by the auditor. It is an opportunity for the auditor to confirm the scope of the audit and the basis on which the organisation will be assessed, together with the plan for the day and other administrative arrangements. The audit team will look to have some space before the end of the day – and possibly at lunch time – to discuss what they have found and to prepare for the closing meeting.

[edit] The audit

1. Guides

The organisation should provide guides for each auditor. They have an invaluable role in supporting the audit and should have a good understanding of the work being carried out as well as the geography of the site. There are a few important points:

- The guide is there to assist the auditor and to support the auditee. Often the guide can support the auditee simply by standing or sitting nearby. There is nothing more off-putting for an auditee than being faced by an auditor and a manager.

- The guide should not answer the questions put by the auditor, but may prompt, especially if the person being audited is nervous.

- The guide should not be the manager of the work being audited, as this may intimidate the auditee.

- The guide should be prepared to uphold any issues that have been found, especially in the closing meeting.

A typical opening meeting agenda can be found in Appendix A

2. Audit Interviews

Audit interviews are a voyage of discovery. They allow the auditor to learn how the management system is operating. This is best learnt from the person being audited.

The interview itself usually takes the form as follows:

- Open questions. These are questions that allow the auditee to describe the work they are doing. Auditees can think about what they might be asked, to be prepared. It can go wrong in some situations, such as a cleanroom in which ladies were counting five items into bags – an open question, such as “Can you tell me what you are doing?” would have been silly.

- Probing Questions. These questions are developed from the answer to the open question together with the list of points the auditor wishes to discuss. They see to gain a full understanding of the work being undertaken and its relevance within the management system.

During this part of the interview, the auditor will seek evidence that the processes are being undertaken as described in the Quality Management System. the evidence can be in the form of work instructions and procedures relevant to the works, inspection and test plans, records and answers to questions posed by the auditor. Note that any guides should only intervene if the interviewee is under difficulty in providing the evidence.

- Closed Questions. These are used to confirm the findings of the interview. It is important that both the auditee and the guide accept the accuracy of this confirmation as it may reappear during the Closing Meeting. The auditor should put the auditee/s at ease and make it clear that that an audit is to confirm that processes are being followed, not a witch hunt to catch people out.

Auditors are not there to interrogate the suspect. The normal technique is to ask a general or “open” question to allow the auditee to provide a picture of what is going on and to encourage detailed responses from the auditee. This is then following by a series of more “probing” questions that seek to provide the auditor with a clear picture of the process and the results of the work being conducted. Auditors should finally confirm their understanding by asking a “closed” question that generally elicits the answer “yes” or “no”.

The auditor needs to take adequate notes to enable him/her to write the audit report, as well as identify tasks and items to be dealt with later. However, notes need to be concise and not interfere with the progress of the audit any more than necessary. Important notes should be taken of any information relating to any potential nonconformities.

The audit report should be written up and presented as soon as possible after the audit so that the audit findings are fresh in people’s minds, but not necessarily on the day that the audit is completed.

3. Audit reporting

An audit report provides a record of the audit in relation to the audit objectives, scope and criteria and the audit findings. Typically, an audit report should include a summary, a description of the areas and activities audited, the audit findings, the personnel involved and the attendees at the opening and closing meetings.

The audit findings enable corrections to be made, corrective actions to be taken, opportunities for improvement to be identified and provide information for management reviews.

4. Non-conformance

At some point, the dreaded “non-conformance” word may appear. It will be defined in both the Opening Meeting and the Closing Meeting and may form part of the report on the audit.

Let us be very clear what a non-conformance is not. It is not a penalty, a red card, a violation, or a punishment.

A non-conformance is just what it says – a difference between what was found during the audit and the expectation based on the documented management system. It may be caused due to a person not following an instruction or it may be that the instruction is incorrect or inappropriate. It needs to be managed out to a point where the system and implementation of the requirement conforms. To this end, the record of non-conformance should have sufficient information to permit another auditor to be able to confirm with evidence that the non-conformance has been corrected. Typically, a non-conformance report will state the following:

- The process being audited.

- The location of the non-conformance

- The statement of non-conformance (what happened)

- The evidence to support the non-conformance

- Timescale for response to non-conformance identifying correction and corrective actions

The procedure, work instruction, standard or contract requirement against which the non-conformance has been raised, together with any other relevant documents. In some cases, observations can be raised. These are no lesser than non-conformances, but may be outside the scope of the audit, warnings of something about to go wrong, etc. The same details should be recorded for observations as for non-conformances.

[edit] The closing meeting

This meeting is also led by the Lead Auditor. It is a unique opportunity to confirm the findings of the audit and to discuss any differences of opinion before the end of the day. It is important that all differences are resolved before the end of this meeting.

The Lead Auditor will re-confirm the scope of the audit and the definitions of non-conformance and observation. Different auditor can have different terms for these. Each auditor will read out the words of each finding in turn. As these have been agreed at the point where they were found, there should be little need for discussion. Sometimes, the auditor reads out a statement of non-conformance and the guide then explains what happened, which can be very helpful.

The Lead Auditor will confirm that all the matters raised will be held in confidence and will discuss what actions come next, for example, actions to be raised and completed, so that any follow-up will be successfully resolved.

A typical closing meeting agenda can be found in Appendix A.

[edit] Follow-up

Audits do find matters that need to be put right and it is the duty of the auditor to confirm that this has happened. When conducting an audit as part of a tender assessment, the follow-up may happen once the contract has been let. In first-party and third-party assessments, the follow-up may be at the next regular audit.

The auditee should undertake a root cause analysis of the audit findings, in particular nonconformities identified, to determine any underlying issues that need to be addressed to prevent subsequent recurrence of the issue.

In responding to a non-conformance, the auditee should identify a correction to address the immediate issue and a corrective action to prevent recurrence of the issue.

The Auditee should respond to the non-conformance raised within the timescale agreed setting out the actions they intend to implement to address the non-conformance.

The auditor should review and either accept or reject the plan for rectifying any non-conformances from the auditee to confirm that it is feasible. This decision will be based on whether the response provides sufficient detail in how the non-conformity will be addressed based on the root cause analysis.

Auditees should create a programme to fix any issues raised during the audit. Interestingly, the guide may notice matters that are not brought to the attention of the auditor, but which need fixing anyway. The audit manager should develop a programme to address the issues raised and use the internal audit system or other means to confirm not only that the issue that was found has been addressed but also that there are no other similar issues that also need to be addressed.

The first matter that the auditor will address on the next audit will be the non-conformances and observations raised during the previous audit, so it is important to prepare to address the results of the corrective actions before the next audit.

The auditor will review whether the actions taken to address non-conformance have been effective in addressing the issue.

[edit] Strategic audit schedule

The strategic audit schedule is generally prepared where the auditing organisation undertakes follow-up and continuing audits to confirm that the auditee has completed any corrective action, is not slipping back and, ideally, showing a pattern of continuous improvement. The schedule can be issued at regular intervals, normally annually or quarterly, but can be based on project delivery, and define the audits to be delivered against projected dates. It should be based on:

- The status and importance of activities being conducted.

- The results of previous audits (internal & external).

- Corrective actions.

- Changes to systems elements.

- Introduction to new methods and technology.

- Organisational and personnel changes.

- The risk to quality if audit frequency is reduced.

- Availability and competence of audit personnel.

Factors to be considered when developing a strategic audit schedule should include: -

- The audit objectives and criteria.

- The audit scope including processes to be audited.

- The dates and places where the on-site audit activities are to be conducted.

- The expected time and duration for the on-site activities including safety/security requirements.

- Persons to be interviewed.

- Competence of auditors.

[edit] Negative distractors

These are ploys that have been used in the past to distract auditors from completing the work. There are several reasons why they should be avoided at all costs:

- Auditors have seen them all before and become irritated by them.

- They don’t work.

- They put pressure on the auditor, who knows that there is something that the auditee is trying to hide.

The Long Lunch

That nice little restaurant a few miles away sounds very inviting but wastes a considerable amount of time. A sandwich lunch or a quick meal in the canteen is more than acceptable.

The Cook’s Tour

Again, time can be wasted by moving from one part of the organisation to another by using long and winding routes. The auditor has seen a plan of the building and knows when this is being done. Travel from headquarters to site can be problematic and potentially time-consuming and the (Lead) auditor will need to make sure that the audit team has time allocated to cover all relevant aspects.

False Amnesia

Pretending to forget can be used to cover up an issue. On many occasions, the issue may simply be one that the auditee feels may get him/her into trouble. The guide can often help here by prompting the auditee, especially if the amnesia is genuine.

The Blue Peter

“Here’s one I prepared earlier”. The auditee has carefully prepared an example to demonstrate that the management system is working well and that the product is wholesome. Most auditors will want to select one or more examples of their own choosing, as this shows the organisation in its true light.

[Note: it is always advisable to be properly prepared across all activities, rather than trying to second guess what an auditor would like to see – the auditor may well bypass any proffered example!

The Fixed Ballot

On occasion, an auditee will claim that the proffered example is the only one that is available for audit. This is a difficult one and, in some cases, it is true that there is only one example. This can happen in software development, particularly when parameterizing a unit to work in a specific way. However, it does make the auditor’s life difficult – and be certain that it is the only one!

Forced Absence

“The person you wanted to talk to is away today”. There can be good reasons for this that were not foreseen at the initial visit. They can happen at the last minute. On the other hand, it has been known for persons who attempt to dish the dirt about the organisation are asked to take a free day off.

If someone is away, it is important to substitute someone who has sufficient knowledge to be able to answer the questions posed by the auditor. Auditors are understanding and will recognise if someone is struggling.

Time Wasting by the Auditee

The search that takes too long, the delay in meeting someone – you name it – there are many ways that valuable time can be taken out of a very tight schedule.

Provocation

Deliberately creating a hostile situation to bate the auditor and disrupt the smooth progress of the audit.

These ones speak for themselves!

- False sincerity

- Language barrier that may or may not be true

- The Trial of Strength or arguments between the auditor and the auditee.

- Pity me

[edit] And finally, a word about bribes

In some parts of the world, bribery is normal and commonplace. However, for the auditor, any attempt to influence the outcome of the audit is to be resisted. This then leads to what is meant by a bribe. Some auditors will not even accept a cup of coffee. Many companies lay down clear instructions that must be followed and it is for each auditor to decide what is acceptable. One guiding rule is that any item that is part of the normal promotional material is acceptable, if it is offered at a time and in a way that could not influence the outcome of the audit, such as after the closing meeting. Auditors should be very aware that in some cultures refusing a gift is an affront to the giver. The offer of gifts is a matter for careful consideration by both the auditee and auditor. On a personal note, I sat down to pull my notes together at the end of an audit and was offered a very fine pen in the company livery to do so. When I looked a little quizzical, the auditee said, “If I was going to bribe you, I would make it worth your while and not just a clicky pen!”

This article was originally written by Keith Hamlyn on behalf of the CQI Construction Special Interest Group, reviewed by Colin Harley, accepted by the Competency Working Group and approved for publication by the Steering Committee on 1st March, 2022.

--ConSIG CWG 21:50, 01 Mar 2022 (BST)

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

Featured articles and news

Global Asbestos Awareness Week 2025

Highlighting the continuing threat to trades persons.

The context, schemes, standards, roles and relevance of the Building Safety Act.

Retrofit 25 – What's Stopping Us?

Exhibition Opens at The Building Centre.

Types of work to existing buildings

A simple circular economy wiki breakdown with further links.

A threat to the creativity that makes London special.

How can digital twins boost profitability within construction?

The smart construction dashboard, as-built data and site changes forming an accurate digital twin.

Unlocking surplus public defence land and more to speed up the delivery of housing.

The Planning and Infrastructure Bill

An outline of the bill with a mix of reactions on potential impacts from IHBC, CIEEM, CIC, ACE and EIC.

Farnborough College Unveils its Half-house for Sustainable Construction Training.

Spring Statement 2025 with reactions from industry

Confirming previously announced funding, and welfare changes amid adjusted growth forecast.

Scottish Government responds to Grenfell report

As fund for unsafe cladding assessments is launched.

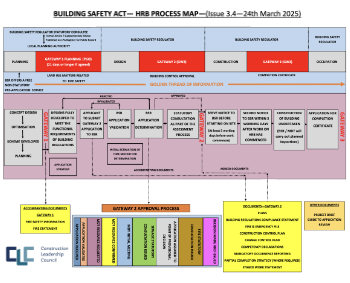

CLC and BSR process map for HRB approvals

One of the initial outputs of their weekly BSR meetings.

Architects Academy at an insulation manufacturing facility

Programme of technical engagement for aspiring designers.

Building Safety Levy technical consultation response

Details of the planned levy now due in 2026.

Great British Energy install solar on school and NHS sites

200 schools and 200 NHS sites to get solar systems, as first project of the newly formed government initiative.

600 million for 60,000 more skilled construction workers

Announced by Treasury ahead of the Spring Statement.

The restoration of the novelist’s birthplace in Eastwood.

Life Critical Fire Safety External Wall System LCFS EWS

Breaking down what is meant by this now often used term.

PAC report on the Remediation of Dangerous Cladding

Recommendations on workforce, transparency, support, insurance, funding, fraud and mismanagement.

New towns, expanded settlements and housing delivery

Modular inquiry asks if new towns and expanded settlements are an effective means of delivering housing.