Digital transformation

Introduction

Terms like “digital” have been part of the common language for the past decades. In the construction sector where tradition and new technologies do not always move at the same pace as in other sectors, like manufacturing, the combination of Digital Transformation (DT) and construction methodologies may be tricky at best.

The article highlights some of the theories and models in the literature, all of which seems converging on a few and critical elements: strategy, planning, market analysis, resource management.

Consequently, digital transformation is not always an easy activity; it can be expensive, challenging, and may require skilled resources. However, some great improvements can be obtained even by small transformations. The use of cloud-based software is one of them.

Like any innovation, digital transformation may start in an unexpected part of the organisation or produce unexpected results – sometimes unintended.

This article aims to investigate what digital transformation is, how it can be achieved, what its benefits and risks are.

Terminology

Digital transformation is only one of the terms used in association with the word “digital” or the prefix “digit”. So, a preliminary clarification of the terminology may support further understanding.

“Digitisation” is intended as the process of converting information from analogue (hard copies of documents) to digital (by using electronic machines, i.e., computers) (Salesforce).

Digitisation was introduced in the 1940s, when Claude Shannon, an American mathematician and considered the “father of modern digital communications and information theory”, presented for the first time his theory that would have evolved soon into the concept of digitisation (Heslop, 2019).

“Digitalisation” is a direct consequence of digitisation: it is about doing what has always been done, but much faster thanks to the technology allowing information to be immediately available (Salesforce).

According to Heslop (2019), the digital transformation started properly in 2014, when the transformation was not just a project undertaken on a “case-by-case” basis but involved the entire documentation process. Examples of digital transformation or failure to perform it existed even before that date, as the case of Blockbuster shows. The company quickly passed from a successful video rent chain of stores, globally recognised to disappearing when Netflix transformed their business from a mail-based DVD rental company into online video streaming. The example embeds some clear elements of the digital transformation:

- The use of new technologies – Blockbuster remained locked to videotapes, while Netflix used the streaming over the internet.

- The reinventing of the business model – the basis was the same, renting videos, but the way to distribute dramatically changed.

- The acceptance of the new model by customers.

Defining what digital transformation is, may not be as easy as it appears, as researchers have investigated the terminology even by interviewing “experts” in various countries. Mergel et al. (2019) conducted a research exploring the different definitions and elements identified during interviews to “public managers on the national, regional, and municipal government levels, IT service providers and enterprises working only for government clients, quasi-government employees from consultancies and, in addition, a representative from the European Commission”. The conclusion of their study highlighted that:

- There could be different definitions depending on the type of public service and how each is prone to engage in the use of new technologies.

- The complexity of the service plays a role in defining what the digital transformation is.

- Various indices are used to measure the transformation, making it difficult to have a single view across all sectors.

- Finally, and probably more importantly, citizens play a critical role as their participation makes it easier for a public administration to achieve its goals.

It can be argued that the above does not represent the entire construction industry, which is done by both public and private operators, with the latter being potentially more flexible than the public one. This is true. However, some similarities can be easily identified also in the construction industry:

- Construction companies are different in size, revenue, culture. Each one may have specific definition of what the digital transformation is.

- The construction industry includes repair and maintenance works as well as new developments valued at hundreds of millions of pounds. So, complexity plays an important role.

- The construction industry is strictly related to its customers. Sometimes the customer is the individual family, other times is well-established holding, if not directly some public entity. This variety can impact the way and the speed the digital transformation takes place.

Reading some of the definitions given by the “experts”, there is a wide variety of topics that are considered part of digital transformation:

- Offering quicker services.

- Offering new services, not only the previous one in a digital way.

- Opportunity to change, not only introducing the technology but using it to improve the work processes (imagine the change that the laser cutting technology has produced).

- The choice of what to transform and what not to. The organisation remains in charge; it is not – or not always – a passive receiver of a new wave of changes: it is offered the option of how to progress.

- Deciding how to deal with what comes from outside the company. Competitors may engage in the transformation, or it can be the market or even the clients.

Something we can agree on is that digital technologies threaten business models, even if well established and based on tradition, and that there are no permanent solutions nowadays (Gupta & Bose, 2019).

Borrowing the research findings from Gupta & Bose about digital transformation in the start-up companies, we believe that some topics also apply to established businesses willing or in need of change. Specifically, the transformation may cause organisations to rethink various parts of the business architecture, such as:

- Relationship and interaction with the client

- Product vision

- Priorities

- Value proposition from the product/service

- Re-segmentation

- Delivery channels

- Partnerships

- Organisation vision and mission

Nambisan et al. (2019) recognise that digital transformation has three themes that are strictly related: openness, affordances, and generativity.

- “Openness” is typical in innovation and entrepreneurship. Digital transformation has impacted it by changing “in terms of degree, scale and scope” – who can participate (actors), how they can contribute (inputs), and to what ends (outcomes) (Nambisan, 2019).

Some examples:

- ** Digital resources are accessible and modifiable by a program.

- Digital architectures allow for building on one another’s contributions.

- Collectives of individuals or organisations “can pursue innovation/entrepreneurship collaboratively”.

- “Affordances” relates to the facilitation of the innovation process in specific contexts thanks to the new tools and infrastructures. “Action potential or possibilities offered by an object (e.g., digital technology) in relation to a specific user (or use context) in innovation and entrepreneurship – for example, digital affordances, spatial affordances, institutional affordances, social affordances”.

Looking at Digital Transformation in terms of affordances and constraints may justify why the same technology leads to different outcomes in different contexts (Nambisan, 2017).

The Cambridge Dictionary defines affordance as "a use or purpose that a thing can have: that people notice by the way that they experience it". “Noticing” the processes is also a critical part of affordances.

- “Generativity” has different meanings. Generally, it refers to the capability to produce something starting from what you have - not necessarily by blending the initial elements in something new but also arriving at an unpredictable result. “Capacity exhibited by digital technologies to produce unprompted change (through ‘blending’ or recombination) by large, varied, unrelated, unaccredited and uncoordinated entities/actors”.

Examples of Digital Transformation in more traditional businesses

The Belgian Westvleteren beer is considered one of the seven best Trappist beers in the world, produced according to the original recipe and with traditional methods. Still, when the customer wants to place an order, he needs to make a phone call or go on a website. For a product whose origins date almost two centuries ago (Trappist Westvleteren, 2022), the use of the phone and internet can be considered digital transformation.

Another example is the glass produced in Murano, Venice, Italy. This glass is highly traditional in its design and fabrication; all is manual and based on the skills of the “artists”. However, customers may purchase an item online, without visiting the shop.

Eventually, even when the entire manufacturing process is done without the use of new technology, like charcoal drawings, the sale of the drawing may still be boosted by new technologies, either directly – by advertising the art online – or indirectly – by client posting photos on social media.

The approach to the bank account has been revolutionised. High street banks keep closing their physical front desk offices, moving to the digital world. Furthermore, the client has ceased to be the one who asks and receives the support from a bank employee: somehow, the client is almost a bank employee in the sense that the majority of operations can be performed directly by the client and, in case of problem, the bank employee will act, remotely, as a kind of supervisor. It is almost like, it is not the bricklayer who builds the wall: it is the client doing it and, in case of trouble, the bricklayer will provide advice.

Similarly, the sale of the airline tickets has changed dramatically, impacting not only the approach of the client to the matter, but even the survival of the travel agencies. The latter are not the preferred contact to buy a cheap flight, as it was in the past: there is an app and the client can (must!) use it. The travel agencies have had to reinvent their business model to provide added value where internet services can be a much cheaper option.

Whatever the case, digital transformation is all around us, either in the most industrialised countries or in the poorest ones. In Uganda, Botswana and Ghana, back in the early 2000s, people were using mobile phone airtime credits as a way of transferring money to relatives, bypassing the banking system and their prohibitive costs. That put the basis for a commercial service offered by M-Cel in 2004 and from there it rocketed in other countries, even outside Africa (Tidd & Bessant, 2015). The combination of existing technology (mobile phones), needs for money transfer and a bit of market analysis allowed for the launch of a successful business model by the mobile companies, expanding the concept of mobile phone airtime credits into proper credit to pay goods and services.

Examples of Digital Transformation in the construction industry

Some digital transformations may already be common in the construction industry. As an example, the use of computer-aided design software, like AutoCAD, which support the design phase and put an end to the use of the technical drawing tables.

One more example is the use of a documentation database, where to store and manage the issuing and revisions of each project documents.

There are examples of tablets being used on site to record the results of tests and inspections with the results being immediately uploaded at the point of inspection/test using Wi-Fi.

Tracking the project moved from a paperwork activity to a digital one, thanks to the implementation of project dashboards. They can be part of more complex software and aim to present the most pertinent information about the project to stakeholders; data can be stored online and shared with the client, facilitating the interaction. The most advanced systems even allow for sharing the status of the construction documentation (inspection reports, nonconformities, authorities' authorisation, material certificates, et al.) real-time as the project progresses; the head quarter has access to the same information as the construction site, regardless of where the site is located in the world. It becomes possible to have all the inputs needed to manage the quality management system remotely:

- Project review meetings do not require long preparation to provide each participant with the documentation package via email or in hard copy: all that is needed is immediately available online;

- Department managers have constant feedback on the status of the activities of their teams on each project;

- Key performance indicators can be collected consistently across all projects and analysed in the head office;

- Different types of reports can be obtained directly from the software and new formats can be created to satisfy virtually any needs;

- Lessons learnt, HSE reports, behavioural observations, and any other information that can be considered worth sharing can be uploaded in the system and made available to stakeholders;

- Audits, either at site or in office, either from the client or a notified body, can be successfully conducted (or at least strongly supported by) simply using a computer connected to the network, where all the required evidence can be shown to the auditor.

Is Digital Transformation needed? Some companies may have not yet transitioned to any of the above-mentioned software and may still be able to perform their jobs effectively and professionally.

So, is digital transformation useless? The answer is no: it is something that needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Will a brick-laying company benefit from AutoCAD or document control software? Maybe not. But, if the company produces prototypes or wants to show the client how the final work will be, then the use of software becomes the preferred way.

Limits of the construction industry

As Tetik et al (2019) stated, construction projects have a fragmented structure: each project has its own life. It can be added that each company has its own life as well, with fewer similarities to other market operators as it can be in the electronics industries, where technological advancement is necessary to remain competitive. Building Information Modelling (BIM), Virtual Design and Construction, and Direct Digital Manufacturing are concepts well known to the industry leaders but remain unknown and of no immediate positive impact for other organisations that are smaller or working in market segments for whom those tools serve no direct purpose or are not worth the economic investment.

Another dimension of digital transformation is the availability of “big data”, which refers to the “data that contains greater variety, arriving in increasing volumes and with more velocity – the three “Vs”” (Oracle). As an example, big data contains information about consumers, their preferences, and expectations. The construction industry may not be up to speed in processing big data but may take indirect advantages from it. A market operator performing industry analysis can arrive at a more precise picture of the market than ever before. Remaining out of this source of information by only focusing on the traditional way of collecting information about their clients can result in a non-winning strategy.

Finally, recent research suggests that digital transformation comes with expectations from the workforces to see their leaders to first transform themselves (Schrage, 2021). The concept is not new to change management: without the leaders leading by example, the transformation is negatively affected.

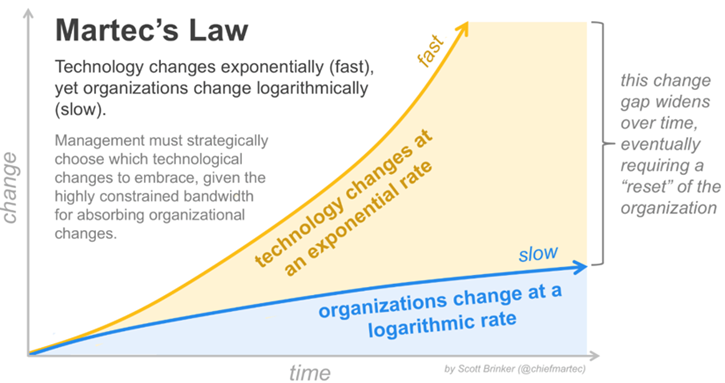

Evolution of a typical company

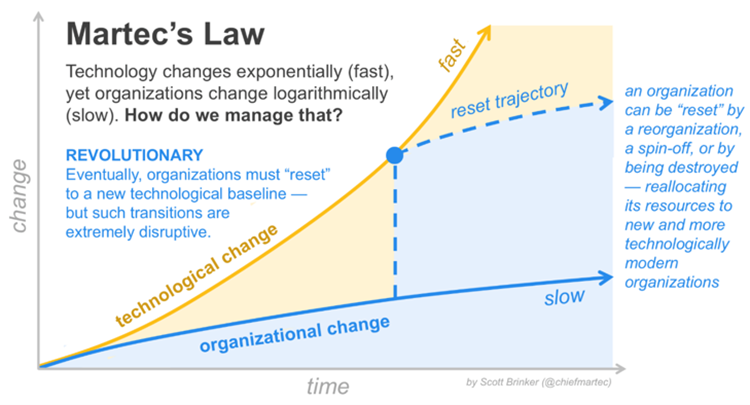

A concept that can easily represent the importance and impact of the transformation for a company is expressed by the so-called Martec’s Law (Brinker, 2013) that states that the technology changes exponentially, but organisations evolve logarithmically, so slower than the former (FinNotes). The following pictures are self-explaining graphical representations of that statement.

Figure 1 - Martec's Law by Scott Brinker

Figure 2 - Martec's Law: agile organisations

The start of the pandemic is reflected in the following picture.

Figure 3 - Martec's Law: what if a cataclysmic event happens?

Figure 4 - Effects of the transformation

Regardless of how much scientifically proven the Martec’s Law can be, it is common sense. Even with all the differences in how steep each curve should be in the construction industry: it can be easily verified in many organisations (if not all of them).

Digital Transformation around the world

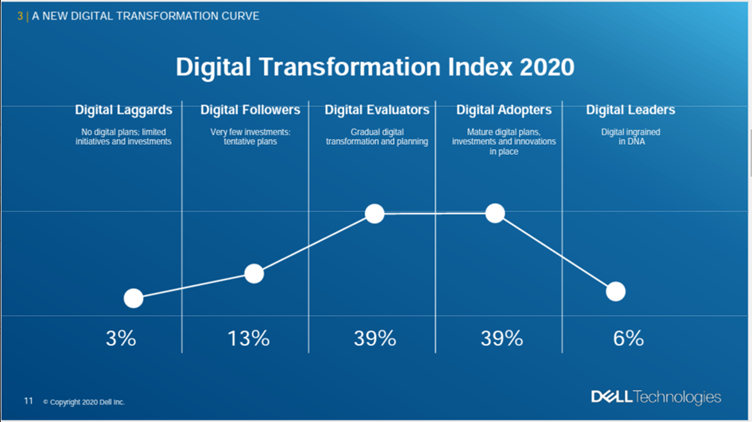

In 2016, Dell Technologies launched a biennial “Digital Transformation Index” as a benchmark to show the status of digital transformation around the world. The 2020 index is based on a survey among 4300 business leaders and shows that 79% of businesses are reinventing their business model because of the pandemic and 50% believe they might not have transitioned quickly enough. Dell classifies the benchmark groups as shown below.

Figure 5 - Dell's benchmark groups for its Digital Transformation Index

The survey gives a picture of how the groups are populated, with the evaluators and the adopters being the highest percentage of the population.

Figure 6 - Digital Transformation Index 2020

Dell’s benchmark is not specific for the construction industry and probably has only considered a few construction companies, if any. However, the classification is useful to test ourselves and check which group our company is more likely to belong to.

Barriers to Digital Transformation

One of the main barriers to digital transformation, as reported in the survey, is the challenge “to extract valuable insights from data and/or information overload,” even though 91% of the businesses considers data analysis of utmost importance.

The McKinsey survey shows that only 16% of respondents reported sustainable performance improvements. The other respondents perhaps fell into one or more of the traps embedded in the digital transformation process which, as any other type of change, needs to be approached carefully. several barriers to the implementation of digital transformation:

- Unclear communication about the meaning of digital transformation, which brings to a lack of employees' engagement

- The foggy target of the transformation process, with the management unable adequately to support the process

- Poor integration of the new tools within the business, also due to lack of collaboration, limited expertise, lack of culture

- Unsustainable returns

- Limited user adoption

- Abandoned projects

The latter can also relate to the difficulty in transitioning older technologies that are not “born digital” into something new. It is the common case of “we have always done this way: why change?” If the market were static, the statement would have found its niche, but, in a dynamic, fluid environment, what has always been done in the same way can become obsolete in the blink of an eye. The pandemic has proven that working from home, something that was considered unrealistic and unproductive, quickly has become the new standard - and it heavily involves a digital approach.

What can make it harder for digital transformation in construction to be successful is due to the characteristics of the industry (McKenzie, 2019).

- Fragmentation – the activity is based on projects, different discipline specialists, vendors, and subcontractors. All that is enhanced by the short-term of the contracts.

- Lack of replication – projects typically are one-of-a-kind endeavours, with customised requirements and tailored approach. Only complex and quite structured projects offer a better ground to implement digital transformation

- Transience – as per the fragmentation, construction projects involve human resources on a temporarily basis, either because they are consultants or construction staff hired for an individual project or because there are different organisations working together only for the duration of the job.

- Decentralisation – the bigger the company, the more segments exist. A global enterprise may be divided into branches, each one working autonomously from the others.

The results are a more challenging process of transformation and the coexistence of similar, competing tools within the same company, resulting in an obvious waste of resources.

Furthermore, the way individuals and companies approach a change involving digital transformation can be tricky as well. Merschbrock et al. (2015) conducted an interesting analysis on a Norwegian construction project trying to understand what the influential considerations for designers are when selecting solutions, and how local system selection decisions may affect the digital work. In doing so, they applied the “Lazy User Theory (LUT),” proposed by Tétard and Collan in 2009. Below you find a personal elaboration of the model based on this theory and the research conducted by Merschbrock et al.

Figure 7 - Merschbrock et al.: selecting solutions

What emerged from the research is the tendency of choosing the solution that offers the least resistance. In doing so, a positive effect is that there is some sort of digital transformation, at least; by choosing a more difficult path, the risk would be that nothing changes.

A reason for not pushing harder in the selection of more appropriate solutions, even though more difficult to realise, is probably down to the lack of understanding of what the benefits of digital transformation can be.

What are the benefits of Digital Transformation?

Digital transformation can produce various benefits:

The increase in competitiveness is, as an example, confirmed by a study conducted on 938 Portuguese companies from different sectors of activity, including construction (Ferreira et al., 2018). The study highlighted that the type of management (old versus young individuals, male versus female) can also impact the early adoption of digital transformation.

- Higher employees’ productivity.

- Higher customer satisfaction through higher responsiveness to customer requests.

- Increased customer loyalty.

- Increased engagement with other stakeholders.

Considerations for implementing Digital Transformation

Companies should be careful before starting a digital transformation. First thing first, they should define which operational changes they want to achieve and then build a “digital use case” that can support the changes. In other words, following blindly the trend of the market is not a good choice. The use case approach has also the advantage to support the identification of new opportunities for improvement.

The characteristics of a good process-centred use case are:

- A process change.

- The required enablers (data and technology tools, capabilities, changes in mandates and responsibilities, legal and contractual requirements, and others).

- The expected benefit.

Eventually, digital transformation does not imply necessarily the use of the latest fancy software. It can consist in an improvement of the communication between construction sites and supply chain to provide feedback on the product defects identified at the site.

The transformation must be done by carefully examining the market and accounting for all the consequences of the change. In detail:

- Develop market intelligence:

- Identify the value that the transformation can produce.

- Develop a roadmap.

- Maintain a clear vision and clear direction, so that all employees can buy in the new change and ensure a smoother transition.

- Account for all the costs and additional resources needed:

- the need for new skills to deal with the new technology,

- the cost of maintenance,

- the risk of disruption if the new technology fails and the company needs to go back temporarily to the status quo.

This latter is a critical point, as the following example from a real case testifies. An engineering and construction company, specialised in chemical industrial plants, received the update of the design software in use to design the fluid process within their plants. The new version was faulty, and the company was able to identify the problem, inform the supplier, segregate the new version and continue working with the previous one; all without direct impact on the production. That result required a strong internal system, which imposed to validate the new software regardless of the certification released by the producer. Missing that commitment, the item produced with the software would have been released on the market with uncertain consequences, both for the safety of the users and the reputation of the company.

A wrong evaluation of the need for the digital transformation could be as harmful as not doing any transformation when needed.

What are the drivers of Digital Transformation?

McKenzie identifies the following drivers:

- Streamline operations/process management – the ability of the new technology to manage data in a more efficient and effective way.

- Improve employee performance/productivity.

- Enhance customer experience/brand loyalty – the simplicity of use and interaction, both with the product and the service offered. This point may appear difficult for all the construction market operators, but it is anyway critical to be considered.

- Enhance product or service innovation, with the possibility to customise the products to the customer’s expectations.

- Address compliance/security requirements.

- Accelerate time to market. As an example, through the automation of repetitive tasks.

- Enhance customer insights, through data analysis.

- Decrease skills gap/acquire new talent. This can be obtained via a work-from-anywhere approach and enhancing collaboration at work.

Building capabilities

Warner and Wäger (2019) developed a process model describing how to achieve successful digital transformation. The model is based on three capabilities (digital sensing, digital seizing, and digital transforming), each one made of three sub-capabilities, further characterised by three elements.

Digital Sensing

Companies should remain vigilant and aware of the ongoing market, by scanning, learning and interpreting information about business trends. The activity, however, comes with a big level of uncertainty about the outcomes. Planning is the key: there could be different variables to consider – like human behaviour versus innovation – however, hypotheses can be produced and tested collaborating with other parties; user behaviours can be investigated; information channels can be monitored to gather the latest news and analysis on markets developments.

Digital Seizing

The agility to seize new opportunities or neutralise threats by avoiding “hubris, deception, bias, and delusion” and experiment with new business models coming with digitalisation.

The company can implement agility with the customer (who can support a better user experience), with business partners (i.e., an ecosystem everyone can contribute to and take advantage of), and with operations (e.g., increasing efficiency and effectiveness) (Sambamurthy et al., 2003).

Digital Transforming

The previous two capabilities allow the company to create and discover new opportunities; digital transforming may be more challenging. Svahn et al. (2017) link transformation to balancing various elements:

- Existing practices and the new capabilities to be built.

- Process and product innovation.

- Interaction between employees and partners.

- The need for adequate flexibility without losing control.

The solution to managing all this is strategy, strategy, strategy!

A graphical representation of the model

The model is represented in the picture below, which shows a personal elaboration from the original article.

Figure 8 - Process Model to build Dynamic Capabilities for Digital Transformation (Warner & Wäger, 2018)

The model presents the interaction of external and internal factors involved in digital transformation. An obvious external trigger is the client’s behaviour, which may require a step beyond the traditional way the organisation has worked to the date. Then, internal resources, decision making, and top management support play a critical role in the transformation. Eventually, digital sensing, seizing and transforming lead to the already discussed review of the organisation strategy and its culture. The model offers a comprehensive view of digital transformation and what it involves. It may not always be easy to understand but can be thoughts provoking and generative of a new vision for the reader. From there, all is about commitment and dedication.

What are the skills and human resources needed?

Digital transformation has led to the born of a new role, the Chief Digital Officer – CDO, not to be confused with the Chief Information Officer - CIO. The CIO oversees all the information processes within the organisation and fills the gap between information technology-IT and other departments and between the organisation’s strategy and its use of IT (Stephens et al., 1992). The CDO is crucial in developing strategy, process, and innovation; the shift in the company culture falls upon him (Haffke et al., 2016). The importance of a digital transformation strategy has been remarked as well by Chanias et al. (2019), who proved with a real case scenario how the strategy is a dynamic process moving between learning and doing and “is continuously in the making, with no foreseeable end”.

The two roles should be part of digital transformation as one maintains the operational information systems, while the other looks to develop an innovative future.

There is not always a need for a CDO. Haffke et al. (2016) proposed four steps to understand if the organisation needs to involve a CDO:

- The pressure for digitisation – coming from external factors (like customer needs and market competition) and internal factors (like aspiration to become or remain a digital leader).

- The need for coordinating the change – elements like the size, the expertise of the company about digital transformation, the culture, should be accounted for.

- The CIO role – will he/she be able to deliver digital transformation successfully?

- Digitisation focus – the areas of the company that more closely interact with the market (i.e., sales and marketing) may have a stronger need for a CDO compared to internally focused areas (i.e., logistics).

CIO and CDO represent an example of a concept quite common nowadays in literature, “organisational ambidexterity” (Chen, Preston & Xia, 2010). It refers to the ability of an organisation “to both explore and exploit,” being able to expand what the organisation is already capable of doing while looking for new opportunities. It can be the case to underline that digital transformation and ambidexterity share common elements. We have already listed the components of the digital transformation; those at the basis of ambidexterity are (Nieto-Rodriguez, 2014):

- Leadership and culture.

- People and skills.

- Structure and governance.

- Processes and methods.

- Systems and tools.

- Enterprise performance management.

What technologies can be used for Digital Transformation?

The use of new software is only one of the ways an organisation can use to implement a transformation. Specifically:

- Use of cloud resources – not only for data storage but also to share resources and gain quicker access to the tools from everywhere (i.e., Microsoft Office Suite that is available online to all employees from any pc or laptop).

According to Bello et al. (2020), cloud computing is “an innovation delivery enabler” for other emerging technologies like building information modelling, the internet of things, and virtual reality.

- Commoditised information technology, which gives an organisation the ability to focus investment and people resources on the IT customisations that differentiate it in the marketplace.

- Mobile platforms, which offer the ubiquity and the flexibility to carry drawings and documents in digital format. Even the raise of non-conformity or performing an inspection can be done via an app.

- Machine learning and artificial intelligence – it may be too demanding for most construction operators; however, it could boost decisions making process about sales, marketing, product development and other strategic areas.

- Automation to release human operators from repetitive tasks. An example is the 3D printing machine deployed recently by Apis Cor to build small houses (apis-cor.com). An entire detached house can be 3D printed in 24 hours by employing only 3 workers (CNBC, 2021).

In the early 90s, the first adopter of 3D printing was the manufacturing industry; later, the construction industry started considering the technology and some architectural models were 3D printed since the early 2000s (Wu, 2016). In a few years, 3D printers will be part of the equipment in use at least to the biggest construction companies and in the future, they may become an accessory as the traditional PC paper printers (assuming we will still need to print on paper).

- Anything that can support speed, efficiency, and innovation. As an example, augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) allow to create the final product as a virtual object the operator can interact with using special goggles and gloves.

UK Government invested £72 million in the Core Innovation Hub with the intent of making the UK a world leader in the latest construction techniques like VR, digital design, and offsite manufacturing technologies (Gov.uk, 2018). How new technologies can be used is shown by an American construction company, Gilbane Building Company, whose approach is summarised in the following video https://youtu.be/lCzzEKofavI.

Conclusions

The article proves that digital transformation is one of those themes that each company, occasionally, needs to deal with and construction industry is not an exception. Either from inside or by others, digital transformation will be brought within the construction industry. For those not striving to keep up, the pain will not be a profit hit but a complete collapse of the business.

So, why not be prepared for that? A good example of what digital transformation should be is described by the 2018 Chief Technology Officer of Capital One Financial Corp., who declared:” We don't just use the latest technologies, we create them and infuse them into everything we do. We think of ourselves as a customer-centric tech company that provides innovative financial services, not the other way around." Any operator, either in the financial sector or not, can be inspired by those words when seeking digital transformation.

References

- Apis Cor (no date). FRANK - a revolutionary robotic 3D printer that will transform the way we think about the construction industry. https://www.apis-cor.com/3dprinter

- Bello, S.A., Oyedele, L.O., Akinade, O.O., Bilal, M., Delgado, J.M.D., Akanbi, L.A., Ajayi, A.O., Owolabi, H.A. (2020). Cloud computing in construction industry: Use cases, benefits and challenges. Elsevier. Automation in Construction. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103441

- Brinker, S. (2013). Martec’s Law: Technology changes exponentially, organizations change logarithmically. ChiefMartec. https://chiefmartec.com/2013/06/martecs-law-technology-changes-exponentially-organizations-change-logarithmically/

- Brinker, S. (2016). Martec’s Law: The Greatest Management Challenge of The 21st Century. https://chiefmartec.com/2016/11/martecs-law-great-management-challenge-21st-century/

- Brinker, S. (2020). Bending Martec’s Law: 2020 Has Taught Us We’re More Agile Than We Thought. https://chiefmartec.com/2020/08/bending-martecs-law-2020-taught-us-agile-thought/

- Chanias, S., Myers, M.D., Hess, T. (2019). Digital transformation strategy making in pre-digital organizations: The case of a financial services provider. Journal of Strategic Information Systems 28 (2019) 17-33. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2018.11.003

- Chen, Preston, & Xia (2010) cited in Buchwald, A. and Lorenz, F (2020). Who is in Charge of Digital Transformation? The Birth and Rise of the Chief Digital Officer. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344087760

- CNBC (2021). Here’s what the first 3D-printed home for sale looks like. https://youtu.be/bj8kZ3llS5E

- Dell Technologies (2020). Digital Transformation Index – Executive Summary. https://www.delltechnologies.com/en-us/perspectives/digital-transformation-index.htm#pdf-overlay=//www.delltechnologies.com/asset/en-us/solutions/business-solutions/briefs-summaries/dt-index-2020-executive-summary.pdf

- Ferreira, J.J.M., Fernandes, C.I., Ferreira, F.A.F. (2018). To be or not to be digital, that is the question: Firm innovation and performance. Elsevier. Journal of Business Research. 101 (2019) 583-590 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.013

- FinNotes (no date). Martecs Law. https://www.finnotes.org/terms/martecs-law

- Gilbane Building Company (2018). Autodesk. Gilbane Uses VR to Validate Prefabricated Construction. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lCzzEKofavI

- Gov.uk (2018). Virtual reality to revolutionise UK’s construction sector. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/virtual-reality-to-revolutionise-uks-construction-sector

- Gupta & Bose (2019). Digital transformation in entrepreneurial firms through information exchange with operating environment. Elsevier B.V. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.103243

- Haffke et al. (2016), cited in Buchwald, A. and Lorenz, F (2020). Who is in Charge of Digital Transformation? The Birth and Rise of the Chief Digital Officer. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344087760

- Heslop, B. (2019). A brief history of Digital Transformation. ContentStack. https://www.contentstack.com/blog/all-about-headless/digital-transformation-history-infographic/

- McKenize (2019). Jan Koeleman, Maria João Ribeirinho, David Rockhill, Erik Sjödin, and Gernot Strube. Decoding digital transformation in construction. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/decoding-digital-transformation-in-construction

- Mergel, I., Edelmann, N., and Haug, N. (2019). Defining digital transformation: Results from expert interviews. Government Information Quarterly. Elsevier. Volume 36, Issue 4, October2019, 101385 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.06.002

- Merschbrock, C., Tollnes, T., Nordahl-Rolfsen, C. (2015). Solution selection in digital construction design – a lazy user theory perspective. Creative Construction Conference 2015 (CCC 2015). Procedia Engineering. Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2015.10.097

- Nambisan,S., Wright, M., Feldman, M. (2019). The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes. Elsevier. Research Policy 48 (2019) 103773 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.03.018

- Nieto-Rodriguez, A. (2014). Organisational ambidexterity. Understanding an ambidextrous organisation is one thing, making it a reality is another. think at London Business School. Organisational ambidexterity | London Business School

- Oracle (no data). What is Big Data? https://www.oracle.com/uk/big-data/what-is-big-data/

- Salesforce (no date). What is Digital Transformation? https://www.salesforce.com/products/platform/what-is-digital-transformation/

- Sambamurthy et al (2003). Cited in Warner and Wäger (2019), p 332

- Schrage, M., Pring, B., Kiron, D., Dickerson, D. (2021). Leadership’s Digital Transformation Leading Purposefully in an Era of Context Collapse. MITSloan Management Review. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/projects/leaderships-digital-transformation/

- Stephens et al (1992). Stephens, Ledbetter, Mitra, & Ford, cited in Buchwald, A. and Lorenz, F (2020). Who is in Charge of Digital Transformation? The Birth and Rise of the Chief Digital Officer. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344087760

- Svahn et al. (2017). Cited in Warner and Wäger (2019), p. 333

- Tetik, M., Peltokorpi, A., Seppanen, O., Holmstrom, J. (2019). Direct digital construction: Technology-based operations management practice for continuous improvement of construction industry performance. Automation in Construction. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2019.102910

- Tidd, J., Bessant, J. (2015). M-Pesa, case study. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. http://www.innovation-portal.info/resources/m-pesa/

- Trappist Westvleteren (2022). Our Story. https://www.trappistwestvleteren.be/en

- Warner and Wäger (2019). Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Elsevier. Long Range Planning 52 (2019) 326-349 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.12.001

- Wu, P., Wang, J., Wang, X. (2016). A critical review of the use of 3-D printing in the construction industry. Elsevier. Automation in Construction. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2016.04.005

This article was originally written by Giorgio Mannelli on behalf of the CQI Construction Special Interest Group, reviewed by Keith Hamlyn and Vincent Pegg, members of the Competency Working Group and approved for publication.

10:00, 10 Jan 2024 (BST)

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- BIM.

- BIM articles.

- Defining the digital twin: seven essential steps.

- Digital engineering.

- Digital Built Britain v BIM.

- Digital information.

- Digital model.

- Digital technology.

- Digital twin.

- Digitalisation.

- Digitisation.

- Digitise.

- How to make the digital revolution a success.

- Immersive Hybrid Reality IHR.

- Internet of things.

- Smart contracts.

- UK digital strategy.

BIM Directory

[edit] Building Information Modelling (BIM)

[edit] Information Requirements

Employer's Information Requirements (EIR)

Organisational Information Requirements (OIR)

Asset Information Requirements (AIR)

[edit] Information Models

Project Information Model (PIM)

[edit] Collaborative Practices

Industry Foundation Classes (IFC)