Well-being and Regeneration: Reflections from Carpenters Estate

Authors: Alexandre Apsan Frediani, Stephanie Butcher and Paul Watt

In October 2012, students from the MSc Social Development Practice (SDP) programme undertook a three-month research project to explore the impacts of regeneration processes on those residents directly impacted. The case centred on the Carpenters Estate, a 23-acre council housing estate in Newham, adjacent to the Olympic Park and the Stratford City development. At the time of the project, the estate was under consideration as the site of a second campus for the University College London. The 700 units of terraced houses, low-storey apartment blocks, and three 22-storey tower blocks were earmarked for demolition by Newham Council, with the residents’ relocation forming a major part of the proposed redevelopment. The SDP team introduced the use of a ‘well-being analysis’ to explore the ways in which this initiative supported or constrained the capabilities and aspirations of Carpenters Estate residents.

The proposed regeneration scheme in Carpenters Estate mirrored similar trends occurring in the area. East London has long been a major laboratory for UK urban policy, dating from the post-War slum clearance and bomb damage schemes right up to the 2012 London Olympic Games. The Games, alongside other recent regeneration programmes such as Stratford City, have contributed towards the radical reshaping of East London‘s physical landscape.(1) With an additional £290m earmarked as a part of the Olympic legacy, this investment has promised to boost tourism, generate employment, and create new homes and neighbourhoods— contributing to the changing image of East London.(2)

Yet questions have been raised regarding the extent to which the unfolding regeneration processes can enhance the employment opportunities, affordable housing and open public space that can benefit low-income East Londoners.(3,4,5) While the rhetoric of regeneration emphasises community consultation, public-private partnerships and the creation of new mixed communities, the reality all too often means displacement, disenfranchisement and marginalization for pre-existing communities that do not benefit from increased investment, or cannot cope with rising property values.(6,7) Such pressures have emerged in the Borough of Newham, where competing claims on urban space have created tensions between residents seeking to maintain their established homes, livelihoods and neighbourhood facilities, and urban policy initiatives that seek to unlock East London’s economic potential.(8,9)

It is within this context, and in collaboration with residents, activists, and researchers, that the exercise in Carpenters Estate examined the proposed regeneration plan on three key dimensions of the current residents’ well-being: secure livelihoods, dignified housing, and meaningful participation (1). The methodology used was based upon Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach (10), which aims to explore the abilities and opportunities of individuals and groups to achieve the things they value. In other words, apart from prioritizing a series of values that local residents attach to the place they live, the study aimed to reveal the existing capabilities to achieve these values, and to reflect upon how on-going neighbourhood changes support or constrain these capabilities.

The tension between official policy rhetoric and residents’ lived experiences was evident throughout each of the three dimensions examined by the SDP students. In relation to dignified housing, residents highlighted the importance of the bonds with their homes and communities that extended beyond their physical house structures. The regeneration process failed to recognize the value tenants, leaseholders and freeholders placed both on their homes and their relationships within their neighbourhood. Similarly, the students who focused on livelihoods security uncovered that this was based upon a far more nuanced set of calculations than was reflected in the ‘cost-benefit analysis’ undertaken by UCL. For residents, livelihoods security was not solely defined by income, but encompassed a diverse set of influences including job security, costs of living in the area, and the ability to access local support networks. Finally, the students who focused on meaningful participation revealed the sense of disenfranchisement felt by residents from the planning process. While regeneration processes theoretically hold the potential to grant residents greater decision- making authority over their lived space, inadequate information from Newham Council and UCL plus various official exclusionary tactics vis-à-vis community groups resulted in prolonged uncertainty, and helped create the feeling of a ‘democratic deficit’.

These findings are discussed in detail in the ensuing SDP report,(11) and in many ways build upon existing studies which have highlighted the detrimental effects of regeneration processes on Carpenters’ residents.(12,13,14,15) However, this examination also offers an example of the added-value of adopting a well-being approach to reveal the priorities and values of existing communities. While the regeneration of Carpenters Estate falls within the wider discourse of creating an ‘Olympic Legacy’- focused on creating long-term and sustainable benefits of the Games for East London citizens - the incorporation of a well-being analysis helps to qualify this process. This allowed for an examination of the intended and actual beneficiaries of regeneration, highlighting where there may be discrepancies between wider city visions and those residents directly impacted. For communities facing similar challenges, a well-being analysis forms a valuable counterpoint to more traditional ‘cost-benefit’ calculations that do not account for the more intangible priorities and aspirations residents attach to their neighbourhoods. Adopting this approach holds the potential to animate those values and voices that may not always be reflected in large-scale planning schemes. It thus can operate as an emerging tool to renegotiate the aims of regeneration, and support the advocacy of more equitable processes of urban development.

Subsequent to the research reported here, negotiations between Newham Council and UCL for the redevelopment of the Carpenters Estate broke down in May 2013. If any future regeneration plans for the Carpenters Estate are to avoid the policy failures highlighted in the SDP report (Frediani et al., 2013), they must embrace genuinely meaningful participation and acknowledge the value the existing neighbourhood has for its residents’ well-being.

Notes

- For the study, the student group undertook a combination of policy analysis and 50 in-depth interviews with residents and key stakeholders. While the scale and timeframe did not permit a comprehensive evaluation of the impacts of regeneration on the Carpenters Estate, the well-being analysis did outline key inconsistencies between the policies and promises of Newham Council and UCL, and the lived experience of residents.

This paper was entered into a competition launched by --BRE Group and UBM called to investigate the link between buildings and the wellbeing of those who occupy them.

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- A measure of net well-being that incorporates the effect of housing environmental impacts.

- Adapting 1965-1980 semi-detached dwellings in the UK to reduce summer overheating and the effect of the 2010 Building Regulations.

- Anatomy of low carbon retrofits: evidence from owner-occupied superhomes.

- Energy companies obligation ECO.

- Estate Regeneration National Strategy.

- Fuel poverty.

- Green deal scrapped.

- Heat Energy: The Nation’s Forgotten Crisis.

- Housing contribution to regeneration.

- Modernist Estates - Europe: the buildings and the people who live in them today.

- The cold man of europe 2015.

- The real cost of poor housing.

- Transitioning to eco-cities: Reducing carbon emissions while improving urban welfare.

- Wellbeing.

- White elephant.

External references

- Anna Minton, Ground Control: fear and happiness in the twenty-first-century city. (London: Penguin, 2012).

- Andy Thornley, ‘The 2012 London Olympics. What legacy?, Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, vol. 4, no. 2 (2012), 206-210.

- Penny Bernstock, ‘London 2012 and the regeneration game’, in Olympic Cities: 2012 and the Remaking of London, eds. Gavin Poynter and Iain MacRury (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009).

- Mike Raco and Emma Tunney, ‘Visibilities and invisibilities in urban development: small business communities and the London Olympics 2012’, Urban Studies, vol. 47, no. 10 (2010), 2069-2091.

- Rob Imrie, Loretta Lees, and Mike Raco, eds., ‘Regenerating London: Governance, Sustainability and Community in a Global City. (London: Routledge, 2009).

- Jacqueline Kennelly, and Paul Watt, ‘Restricting the public in public space: the London 2012 Olympic Games, hyper-securitization and marginalized youth”, Sociological Research Online, vol. 18, no. 2 (2013).

- Andrew Wallace, Remaking Community? New Labour and the Governance of Poor Neighbourhoods. (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010).

- Nick Dines, ‘The disputed place of ethnic diversity: an ethnography of the redevelopment of a street market in East London’, in Regenerating London: Governance, Sustainability and Community in a Global City, eds. Rob Imrie, Loretta Lees, and Mike Raco (London: Routledge, 2009).

- Paul Watt, ‘’It’s not for us’: regeneration, the 2012 Olympics and the gentrification of East London’, City, vol. 17, no. 1 (2013), 99-118.

- Amartya Sen, ‘Development as Capability Expansion’, Journal of Development Planning, vol. 19, (1989), 41–58.

- Alexandre Apsan Frediani, Stephanie Butcher, and Paul Watt, eds., ‘Regeneration and well-being in East London: stories from Carpenters Estate’, MSc Social Development Practice Student Report, 2013, .

- Open University , ‘Social Housing and Working Class Heritage’, 2009.

- Site/Fringe, ‘On the Edge: Voices from the Olympic Fringe – Newham and Hackney’, 2012.

- Peter Dunn, Daniel Glaessl, Cecilia Magnusson, and Yasho Vardhan, ‘Carpenter's Estate: Common Ground.’ London: The Cities Programme, London School of Economics, 2010.

- Paul Watt, ‘’It’s not for us’: regeneration, the 2012 Olympics and the gentrification of East London’, City, vol. 17, no. 1 (2013), 99-118.

Featured articles and news

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

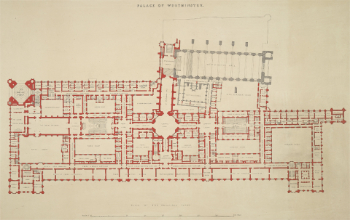

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.

The first line of defence against rain, wind and snow.

Building Safety recap January, 2026

What we missed at the end of last year, and at the start of this...

National Apprenticeship Week 2026, 9-15 Feb

Shining a light on the positive impacts for businesses, their apprentices and the wider economy alike.

Applications and benefits of acoustic flooring

From commercial to retail.

From solid to sprung and ribbed to raised.

Strengthening industry collaboration in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Institute of Construction and The Chartered Institute of Building sign Memorandum of Understanding.

A detailed description from the experts at Cornish Lime.

IHBC planning for growth with corporate plan development

Grow with the Institute by volunteering and CP25 consultation.

Connecting ambition and action for designers and specifiers.

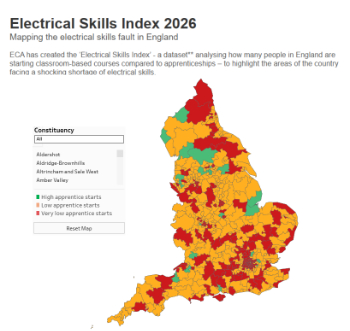

Electrical skills gap deepens as apprenticeship starts fall despite surging demand says ECA.

Built environment bodies deepen joint action on EDI

B.E.Inclusive initiative agree next phase of joint equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) action plan.

Recognising culture as key to sustainable economic growth

Creative UK Provocation paper: Culture as Growth Infrastructure.