Social housing

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Social housing is the term given to accommodation which is provided at affordable rates, on a secure basis to people on low incomes or with particular needs [citation needed]. Social housing properties are usually owned by the state, in the form of councils, or by non-profit organisations such as housing associations.

As of 2015, 17% of all households in England were social housing.

The principle of social housing is that where the private sector is unable to provide the required level of affordable accommodation for all those who need it, the state must intervene to ensure that those on low incomes are provided for. The provision of social housing is seen as a key remedy to housing inequality, as rent increases are limited so they remain affordable to those most in need.

In the private rental sector, tenancies are offered by landlords to whoever agrees to pay the rent according to the terms of the contract. By contrast, local councils allocate housing according to the availability in the particular area at the time, and who is or isn’t eligible for their waiting list.

Local authorities must give certain groups ‘reasonable preference’ on their waiting lists. These are likely to include those who are:

- Have disabilities or specific medical needs.

- Elderly.

- A single parent.

- Living in unsanitary or overcrowded housing.

- A large or young family with dependent children.

- A migrant, refugee or asylum seeker.

- Legally classed as homeless (or threatened with homelessness).

Individuals may be classified as ineligible who:

- Are subject to immigration controls.

- Have not lived in the particular area for a long enough period of time.

- Are believed by the local authority to be guilty of unacceptable behaviour.

- Have breached the terms of a previous tenancy.

Although they are obliged to make a proportion of lettings available to those applicants approved by local authorities, housing associations are free to operate their own waiting lists and lettings policies.

The Right to Buy scheme that was introduced during the premiership of Margaret Thatcher gave council tenants the ability to buy their home at less than the full market value after having lived there for at least 2 years. This policy has, however, been blamed for the subsequent shortage of available social housing provision in the following decades.

[edit] History of social housing

[edit] Industrial England

During the industrial revolution of the 19th century, cities began expand rapidly as labourers flocked to urban centres in search of work. Private for-profit builders provided the majority of house building during this time which meant that the bulk of the population rented from landlords.

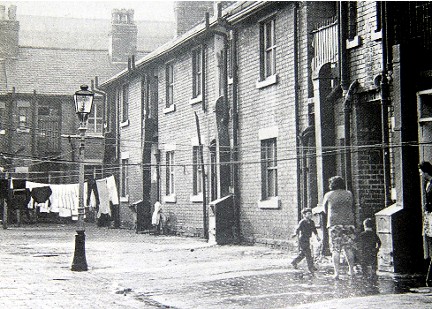

As urban populations grew, conditions deteriorated. High-density housing and lack of adequate facilities resulted in poor sanitation and deprivation that made some areas little better than slums. Friedrich Engels famously documented this problem in his 1845 book ‘The Condition of the Working Class in England’.

During the second half of the 19th century, the government tried to address these issues through various Acts of Parliament, one of which sought to provide private Common Lodging Houses that were essentially dormitories for the poor. At this point, councils still had very little involvement in the building of houses, which were by-and-large supplied by private builders.

[edit] Post-First World War

During the First World War there was virtually no building activity, which meant that at the war’s end in 1918 there was a real shortage of proper housing, combined with the fact that scarce materials and labour had inflated private rents.

Prime Minister David Lloyd George made a pledge to provide ‘homes fit for heroes’, effectively capturing the mood of the time which sought to clear the worst slum areas and address the problem of working class living conditions.

The Housing and Town Planning Act 1919 established Housing Committees that oversaw the building of new housing through the provision of subsidies. It was at this time that suburban ‘garden cities’ first emerged as an idea for new developments on the outskirts of cities, promoted as a new model for living.

The Becontree estate in Dagenham became the largest council housing estate in the world, with 100,000 people having moved to the area by 1932.

[edit] Inter-war years

The Wheatley Act 1924 was brought in to tackle the persistent problem of home affordability for the poorest in society. This sought to scale back the size and standard of housing and encouraged councils to develop estates at a higher density.

By 1933, councils were prioritising the clearance and replacement of inner-city slum areas that were often unfit for human habitation. Following the Housing Act 1930, rents were set much lower so that those being relocated and re-housed as part of the slum clearances would stand a better chance of affording the new houses.

[edit] Post-Second World War

Britain faced a major housing shortage again at the close of the Second World War, due to a combination of a lack of new building work during the war and the damage to inner cities during the Blitz. Aneurin Bevan, a leading minister of the Labour government newly elected in 1945, set about planning a comprehensive housing programme which focused on local authorities rather than private sector involvement.

An initial measure that was intended to be temporary was the rapid construction of over 150,000 ‘prefab’ bungalows, however, they proved more popular than expected and were gradually replaced by permanent housing over a much longer time-frame than originally planned.

By 1955, 1.5 million new homes had been built which relieved some of the pressure for supply. By this time, local authorities let to over a quarter of the population, up from 10% in 1938.

[edit] New urban visions

With the election in 1951 of a new Conservative government, sizes and standards of new council housing were reduced, with the private sector given much more involvement.

The gradual clearance of inner-city slums meant that architects and city planners were able to put into practice modern theories on urban design for the first time. ‘Streets in the sky’ was the term used to describe the new tower blocks that were built during the 1950/60s, which sought to encourage a sense of local community with mixed estates of low and high-rise building.

One of the main drivers behind this vertical growth in council housing was the type of subsidy available. New houses built to replace slums were eligible for subsidies, which increased for buildings of six storeys or more. By the 1960s, over 500,000 new flats had been built in London alone.

As a result of the demand of the ‘baby boom’ generation, as well as the increasingly ageing population, the focus on inner-city council house development shifted to the creation of peripheral estates that were located on or close to the edge of major cities. As with the inner-city tower blocks that quickly developed bad reputations and an association with crime and deprivation, these peripheral estates were often not adequately provided for in terms of local infrastructure which exacerbated a sense of disconnection from the urban centre.

[edit] Right to Buy

The Right to Buy scheme was introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government in 1980 to help council housing tenants (and some housing association tenants) buy their homes at a discount from the full market value of the property. This was partly a response to councils building fewer homes, instead focusing on maintaining the country’s aging housing stock.

Right to Buy was a considerable success for those in a position to be able to benefit from the discounted price being offered, as the value of those properties has since increased greatly. However, if judged by the provision of housing for the lowest earners and most vulnerable in society, then the scheme draws rather more criticism.

Nationwide, 1 million houses were sold within a decade, and as a result the stock of council housing steadily fell.

Read more about Right to Buy here.

[edit] Social housing today

The Department for Communities and Local Government is responsible for overseeing the social housing sector, which regulates and funds registered providers through Homes England. This agency is responsible for the construction of new social homes.

Shelter estimate that there are more than 1.8million households waiting for a social home, an increase of 81% since 1997. Two-thirds of households on the list have been waiting for more than a year. In addition, nearly 41,000 families with dependent children were living in temporary accommodation at the end of 2012. The central cause for this is the lack of social homes built since the 1970s, whilst demand has continued to soar.

The controversial ‘bedroom tax’, introduced in April 2013, sought to reduce housing benefit according to an individual or family ‘under-occupying’ their home (i.e. more bedrooms than the new rules stipulate as being needed).

The Localism Act was introduced in 2011 to change the rules on tenancy lengths for social renters. This allowed social landlords to let short-term contracts of five, and sometimes as little as two, years.

In 2015, the government proposed extending the Right to Acquire scheme to a further 500,000 housing association tenants and giving them the same discount as council housing tenants under the Right to Buy scheme. In September 2015, the National Housing Federation proposed an alternative voluntary scheme for housing associations, which communities secretary Greg Clark accepted, on the condition that the sector agree the proposals within a week of the announcement. Agreement was confirmed in David Cameron's speech to the Conservative Party conference in October 2015.

See Right to buy extended to housing association tenants for more information.

As an amendment to the Housing and Planning Bill 2015, the five-year limit on new tenancies was introduced, aiming to phase out the principle of council tenancies for life. At the end of the fixed term, the relevant local authority will have to carry out a review of the tenant’s circumstances before deciding whether to grant a new tenancy, move the tenant into a more appropriate social rented property, or terminate the tenancy.

[edit] Affordable housing

Affordable housing is a generic term used to describe housing that is affordable to lower or middle income households. In the UK it has taken on a particular meaning defined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) in a way which implies that state intervention is necessary to make housing affordable.

There are a wide range of measures under the banner ‘Affordable Homes Programme’:

- Affordable Rent - rented homes made available to tenants at up to a maximum of 80% of market rent and allocated in the same way as social housing.

- Affordable Home Ownership - a range of home ownership products that enable people to join or move up the housing ladder, through the Help to Buy programme (Help to Buy equity loan, Help to Buy shared ownership and Armed Forces Home Ownership Scheme).

- Empty Homes – intended to bring the 3% of total housing stock which remains empty back into use.

- Mortgage Rescue Scheme - to support vulnerable owner-occupiers at risk of repossession.

- Affordable Homes Guarantees Programme - guaranteeing debt to help housing providers expand the provision of purpose-built private rented and affordable housing.

- Rent to buy - low-cost loans for housing providers.

See Affordable housing for more information.

[edit] Other definitions

Sections 68 to 71 of the Housing and Regeneration Act 2008 defines social housing for the purposes of regulating social landlords as low-cost rental and low-cost homeownership accommodation. The 2008 Act refers to accommodation at rents below market rates and let to people whose needs are not adequately served by the commercial housing market.

Under section 70(2) of the 2008 Act, low-cost home ownership is defined as incorporating shared ownership, equity percentage arrangements and shared ownership trusts. As with low-cost rented housing, these dwellings must be “made available to people whose needs are not adequately served by the commercial housing market” to qualify as social housing.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- 100 years of council housing.

- A new deal for social housing.

- Achieving net zero in social housing.

- Affordable housing.

- Affordable rented housing.

- Back-to-back housing.

- Buy-to-let mortgage.

- Cohousing.

- Converting office and retail to residential housing on the high street.

- Favela.

- Gentrification.

- Help to buy.

- Homes England.

- Housing associations.

- Housing tenure.

- Intermediate housing.

- Interview with David Orr, NHF.

- Municipal Dreams: the rise and fall of council housing.

- Peter Barber - interview.

- Private rented sector.

- Private-rented sector regulations.

- Public v private sector housing.

- Regeneration.

- Right to acquire.

- Right to buy.

- Right to rent.

- Shared equity / Partnership mortgage.

- Shared ownership.

- Social housing rents.

- Social housing v affordable housing.

- Social rented housing.

- The full cost of poor housing.

- Town and Country Planning Act.

[edit] External references

- Shelter

- University of the West of England - Council Housing

Featured articles and news

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.

Heritage staff wellbeing at work survey.

A five minute introduction.

50th Golden anniversary ECA Edmundson apprentice award

Showcasing the very best electrotechnical and engineering services for half a century.

Welsh government consults on HRBs and reg changes

Seeking feedback on a new regulatory regime and a broad range of issues.

CIOB Client Guide (2nd edition) March 2025

Free download covering statutory dutyholder roles under the Building Safety Act and much more.

AI and automation in 3D modelling and spatial design

Can almost half of design development tasks be automated?

Minister quizzed, as responsibility transfers to MHCLG and BSR publishes new building control guidance.

UK environmental regulations reform 2025

Amid wider new approaches to ensure regulators and regulation support growth.

The maintenance challenge of tenements.

BSRIA Statutory Compliance Inspection Checklist

BG80/2025 now significantly updated to include requirements related to important changes in legislation.

Shortlist for the 2025 Roofscape Design Awards

Talent and innovation showcase announcement from the trussed rafter industry.

Comments

[edit] To make a comment about this article, or to suggest changes, click 'Add a comment' above. Separate your comments from any existing comments by inserting a horizontal line.