Internally insulating a historical building. An experimental DIY approach

[edit] Setting the scene

The project discussed here is in an old house with solid granite stone walls approximately 500 mm thick, and without a DPC or membrane as it was built in around 1600. The external faces of the building have been rendered, initially with lime but then probably with a cement mortar mix in the 70s–80s. The internal face of the front wall is exposed granite stonework with sand and cement pointing from the same period. The rear wall and the wall that is the focus of this project, internally had original lime plaster, with areas of patch gypsum plastering, particularly around the windows and elsewhere. This is followed by many layers of paint added over the years, most likely non-breathing paint, with the most recent finish being glue and then a patterned wallpaper.

The cottage is rented mainly as a summer holiday let, as this the largest bedroom has always been cold and the rear wall always damp, and each year the wall paper needed to be stuck back down. The causes of this are assumed to be partly because it is a first-floor wall and very exposed to driving rain and wind (costal location), and possibly because it has quite minimal overhangs at the eaves (historically, it was originally thatch), and there may be issues with the condition and size of gutters. The house is heated with night storage heaters, and although the loft has been insulated, the low eaves mean the pitched ceiling at the tops of the walls internally has minimal insulation, if any, as the other side is the ventilation space under the roof.

[edit] Limitations in approach

In terms of the wall, advice in the past has been that the correct way and proper (maybe purist) approach renovation, would be to remove all the existing external render and internal plaster to expose the stonework fully, clear any cement mortar between the stones and effectively start from scratch with fully breathable lime-based, possibly hemp insulative plaster product. However, due to time and cost restrictions, as well as practicality (scaffolding required externally etc) this approach would most likely never be done. One option would be to remove the plaster internally, start again with lime, and then do the external face later, but again, time and costs restrict this.

Having looked at the variety of insulating plasters it was decided to stay away from organic-based materials, such as hemp shiv, cork, etc. because of the continued risk of damp in the wall and the potential for this to lead to rot within the wall containing organic materials. So with all these elements considered, the options seemed to point towards a mineral-based solution, which in theory implies less risk associated with rotting, minerals such as perlite, and a lime based product with a potentially greater threshold to cope with some damp issues, if there are any persisting, but improving thermally efficiency as well as breathability, at least internally.

Another challenge had been drying time, because, as a holiday let, the warmer periods are primary rental times, and the windows in between bookings can be short. Many lime-based products take time to dry, even in the correct season and, as such, often can’t be quick in and out fix. Though this varies considerably with hydraulic and non-hydraulic lime, it also varies, it seems, with individual products. One lime-based product researched seemed to have a similar drying time to gypsum and offered a mineral based thermally insulating product, so it was investigated further. Convinced of the drying time, and after speaking on the phone, the advice was familiar: to ideally remove all internal plasterwork, all render, and start from scratch. They offered three products as a package: a thermal product, a hemp-based product, and a finished lime coat, all with similar drying times depending on thickness.

[edit] A somewhat experimental plan

Knowing it simply wouldn’t be possible to follow all the recommendations entirely, ie getting back to the stonework either internally, externally or both and with some awareness of the risks involved, it was decided to test a best a possible approach. That would be to score as deeply as possible the existing internal plasterwork and prepare it with a primer, this would give some key for the new plaster and to some extent create breathable slots in the existing finish. Knowing also the chances of having a dry surface to paint on in time were unlikely, meant earmarking the possibility of using pigments to speed things up, though this was also, clearly and understandably not recommended by the supplier. Manufacturers need to be 100% sure their product will be used as recommended in order to be sure it will function as advertised, and adding pigments or unspecified aspects can inevitably change performance. None the less progression was made with this essentially un recommended approach, a kin to to testing the product beyond its specification and seeing where the project managed to get to in the three weeks before the next guests were due to arrive. The thought of sticking down wall paper for yet another year and filling it with gypsum just didn’t make sense, so though not the perfect or recommended solution, it seemed the better or at least most feasible of the options on offer.

[edit] Preparing the walls

So stage 1 was to remove all of the existing wallpaper and then inspect the surface, which was a mix of layers of dry glue, years of magnolia paint, older green paint, on top of primarily lime plaster along with various patches of gypsum. The issue with this, being that any breathability of the wall had essentially been lost through the historical renovation layers, though one might question to some extent the breathability of what was a granite stone wall, except through the lime mortar joints.

So the plan being to score through this build up as deep and as much as possible, as well as remove the gypsum plaster where ever possible. Essentially cutting through this layer was, in the absence of being able to remove it completely, the minimum recommendation from the manufacturer. So using a chisel to start, and slowly moving to an electric cutting tool, to create cuts of around 5-10mm deep, primarily on the inside face of the external walls but also on the faces of the internal solid supporting walls. It is worth noting, as an observation the difference between gypsum plaster and lime plaster, in that where there were sections of gypsum, they were very hard and noticeably damper. They were very hard to remove and would come off as large pieces, taking much of the lime with them, leaving a darker, damper area of wall below, an indication of the difference between the lime and the gypsum's hygroscopicity.

[edit] Constructing the insulation framing

Then the next stage was to build the extra rafters at the internal ceiling pitch to allow for the secondary insulation, which meant investigations in the loft to measure where the ceiling joists and the rafters lay, so as to be able to fix the new timbers to these from the underside. As there would be some weight hanging from these timbers, it was important to make sure they were strong enough, with a framework of timber to timber fixings, packed with mineral wool insulation between, thus the upper plaster board layer, with the original plastic sheet on the outside, effectively become a moisture barrier, with the ventilation gap above and then the roof slates, below the existing plasterboard become the new improved thermal line of the envelope, finished internally with a wood-wool board and then lime plaster. Once packed with mineral wool, the wood-wool boards (which are strands of timber compressed with a lime solution to make the hard, breathable and lightweight board) were then fixed to the new timbers. This installation required special plastic washers, to prevent the fixings from driving straight through the board, these lugs or washers hold it in place.

[edit] Primer and mesh

All of the walls, and deep into the cuts being primed with an appropriate lime primer and left to dry. A plastic gauze mesh sheet which gives extra grip for the lime plaster, and prevents cracking as the different substrates (the board and the scratched wall) move and dry at different rates, was then fixed.

It was laid from the top of the boards down the face and some way onto the walls below. This was quite fiddly, and partly fixed with the washers, though the better way may have been to lay a thin first coat of plaster and then press the gauze into this to hold, until a second coat is applied.

[edit] Testing different plasters to the different surfaces

Next stage was to use the thermal insulation applied to the lower walls, and then up to the boards. But it came to the angle boards, the thermal product felt very gritty as if it wasn’t taking to the board correctly. A test was carried out using the finish plaster but this seemed to be too thin as it dried and allowed the washer rings to show through the plaster. So after double checking with the manufacturer and taking advice, extra bags of the hemp shiv product were bought to apply to the upper boards to build it up, and blend down to the thermal plaster below, to all be finished in finish coat.

One of the advantages of this manufacturer was their product range, which were essentially three products that could be combined, in a similar way that standard builders and gypsum manufacturers use, a bonding coat and a finish coat. This makes the use of lime in some ways more familiar to the general builders market, rather than only to a specialist lime specialist market. There is the hemp shiv coat, which is similar to what one might call a bonding coat in gypsum plaster, the thicker grittier thermal coat with mineral perlite added and then the final, finer and thinner finish coat of plaster. The application per pass being thickest with the thermal coat, around 10-15mm per pass and thinnest with the finish coat, between 3-6mm and the bond cost between 5 and 10mm.

[edit] A word of warning

Despite having worked with gypsum plaster, there was quite a lot of trepidation about using lime, but actually these products seemed to work in a very similar way. The product initially hardened relatively quickly, despite the moist weather conditions, and water could always be added, to the mix of hardening too quickly, unlike gypsum, which has a point at which it can becomes too lumpy to apply and too hard for water to be added. The use of lime does though, come with an extreme warning, which was reinforced the hard way. Having bought water proof gloves, it was discovered that the rear side of these were actually not rubber but textile, which at some point got wet, seeped into the gloves and caused mild burns. A brief pause to check and buy fully rubber gloves, front and back solved this issue, and don't forget goggles and cover all skin, where possible, chemical burns are at minimum not pleasant and worst very dangerous!

[edit] Applying the first lime plasters

Application of the thermal plaster was around 10-15mm at a time, and between two to three coats, though this was obviously thicker where it curved across at the angles with the pitched boards and in the corners which (also helpful because these are effectively the weakest points from a thermal perspective). This was also helped by the nature of the finish and the building being worked on which was a homely, rustic, feel, so curved rather than pristine orthogonal lines and square corners, though no doubt the product could do both, this would just a matter of the skill level in application. So with about 25-30 mill of thermal insulation plaster on the external walls and around or 10-15mm of hemp Shiv plaster on the boards and a kind of mix of both at the horizontal curves. The window was very difficult to finish neatly.

In hindsight too much time was spent trying to get a perfect first coat, where as the first coats can be quite rough, with the differences picked up with the finish coats. Around 28 bags of plaster, were used around 4 of which were finish, 8 hemp shiv or bonding coat and the rest thermal plaster. The amounts calculated using the square metreage and the manufacturers guidance, which was about right, if maybe slightly short, due to lack of experience in plastering and a certain amount landing on the floor ! The internals walls, which were not exposed to the elements externally received only the lime primer, hemp shiv and finish coat of plaster.

The skirting boards had been removed at the start and because of the increased thickness had to be cut down, as the finish cured, which it did quicker than expected, despite the thickness. However, guidance suggested continually wetting the surface, so as not to dry too quickly and waiting a number of days before overpainting (with a breathable paint). Time was extremely short and with guests due to come by the end of the week, despite using a dehumidifier also, it wasn't going to be possible to over paint.

[edit] Applying an experimental finish coat

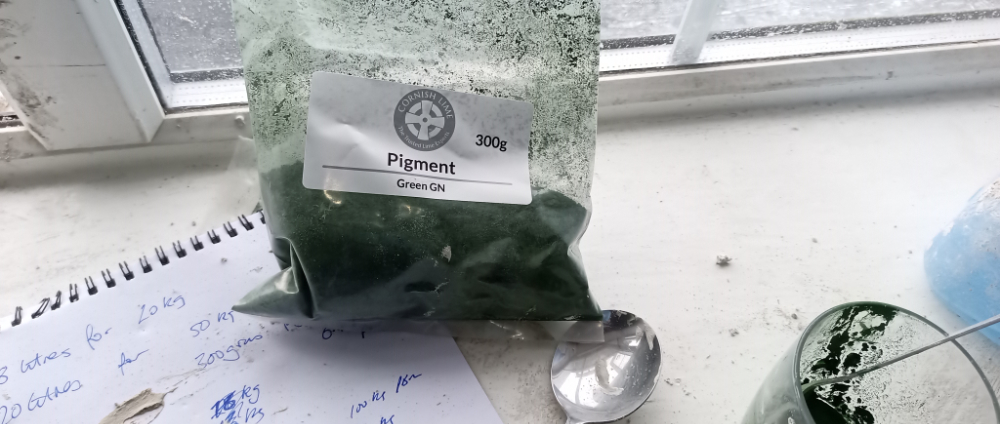

So the last and final part, in the circumstances, essentially running out of time, another choice was made, again one not fully recommended by the supplier. That was to use a pigment in the final coat of the lime plaster, to avoid leaving a pink / grey patchy wall for the next guests. The use of pigment, also from a different manufacturer, essentially introduced a significant unknown element for the lime plaster supplier and thus totally reasonable for them to advise against it, but I was running out of time and needs must as the devil drives. So testing with the pigment began.

Initially less than a teaspoon full of pigment, mixed with warm water was added to a small bucket of finish lime plaster mix, plastered on parts of the wall, to see what the colour was. It was a guessing game really, in the end using around 4 heaped teaspoonfuls per packet of plaster, first prepared with warm water to dissolve the pigment, added to the mixing bucket and mixed, then applied and hoped for the best.

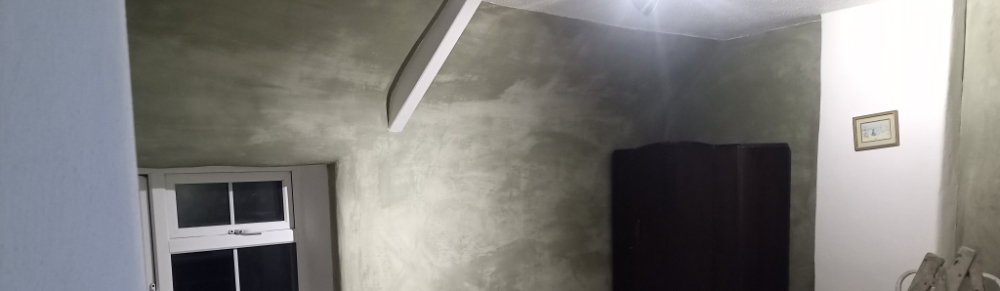

Having spent quite some time trying to get neatly applied plaster lines in most areas, it was a struggle around the window opening, because of the uneven surface. So rightly or wrongly, a sponge finish seemed the only way to get some form of smooth even finish. This was possibly done too early, out of a desperation to get finished, which meant leaving a somewhat gritty rather than smooth surface, but once the sponge had started to be used, there wasn't really any going back. A lot of questioning over the darkness of the surface, the finish of the surface being unsure how it would look, mainly because of the sponging but also the pigment, hoping because of the rustic feel, it might just fit.

By the time it came to leave, it was what it was, and felt quite dark, but visiting some 6 months later and from the feedback of guests, it was a different, but charming finish, that we have come to be fond of. Most importantly the combination of improved, loft insulation, eaves insulation and the thermal plaster, have dramatically improved the temperature of the wall and the ability of the space to retain its heat.

So all in all, as a DIY project, though challenging, it was deemed a success and a good fit for that 16th Century cottage.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Binding agent.

- Cement mortar.

- Defects in brickwork.

- Defects in stonework.

- Dry hydrate lime mortar.

- Grout.

- Gypsum.

- Harl.

- Hemp lime construction: A guide to building with hemp lime composites.

- High alumina cement.

- High lime low alkali glass.

- Hot-mixed lime mortar.

- Hot-mixed mortars: the new lime revival.

- Hydraulic lime.

- Hydrated lime.

- Lime based thermal plaster part 1.

- Lime concrete.

- Lime mortar.

- Lime mortars vs. cement.

- Lime plaster.

- Lime putty mortar.

- Lime run-off.

- Mortar.

- Mortar analysis for specifiers.

- Non hydraulic lime.

- Pointing.

- Portland cement.

- Rendering.

- Soda-lime glass.

- Stucco.

- Types of mortar.

- The use of lime mortar in building conservation.

- Types of mortar.

Featured articles and news

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.

Many resources for visitors aswell as new features for members.

Using technology to empower communities

The Community data platform; capturing the DNA of a place and fostering participation, for better design.

Heat pump and wind turbine sound calculations for PDRs

MCS publish updated sound calculation standards for permitted development installations.

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.