Cool roofs

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Cool roofs are roofs that stay cool in the sun by minimising solar absorption and maximising thermal emittance (Akbari 2008).

“Substituting a cool roof for a non-cool roof decreases cooling-electricity use, cooling-power demand, and cooling-equipment capacity requirements, while slightly increasing heating-energy consumption. Cool roofs can also lower citywide ambient air temperature in summer, slowing ozone formation and increasing human comfort. “ (Akbari 2008)

The subject areas of cool roofs, surface solar absorption and emittance, Urban Heat Islands (UHI), urban air pollution, and building and city level cooling energy requirements are all highly interrelated. Literature on these issues is vast but much more work is required to implement findings and realise potential benefits in the real world.

The parameters of a roof's surface can have a large influence on the surface temperature of the roof. During clear sky conditions, up to approximately 1kW/m2 of solar radiation can be incident on a roof surface, and typically, between 20% and 95% of this radiation is absorbed (Suehrcke, Peterson et al. 2008). This large range can be explained by the influence of the surface parameters on heat gain.

The main parameters which influence maximum roof surface temperatures are solar absorptance, infrared emittance, and the convection coefficient (Berdahl and Bretz 1997). Roofs that have high solar reflectance (high ability to reflect sunlight) and high thermal emittance (high ability to radiate heat) tend to stay cool in the sun (Akbari, Levinson et al. 2008).

The colour of roofs can significantly influence the temperatures they reach. The term 'albedo' designates the total reflectance of a specific system. White can be effective in minimising heat transfer into buildings as it is a poor absorber of energy and a good emitter (Al-Homoud 2005). The general idea of white washing structures to reject heat has been known since antiquity (Berdahl and Bretz 1997).

However, colour is not always a good indication of the albedo of a surface as it depends not only on visible reflectance but also reflectance of Infra Red (IR) light. For example commonly used 'white' coloured roofing shingles and galvanised steel run 35oC and 43oC hotter than air temperature on a sunny day. Conversely, surfaces painted with red or green acrylic paint run only 22oC hotter, even though they are not visibly bright (Rosenfeld, Akbari et al. 1995). Galvanised mild steel gets hot, not due to its low albedo but because of its low emissivities meaning it is slow to cool by radiation (Rosenfeld, Akbari et al. 1995).

Whilst increasing roof albedo and infrared emittance can reduce energy consumption in hot climates, it may increase heating-energy consumption in winter months or in cooler climates (Akbari, Levinson et al. 2008).

[edit] Quantification

Quantitative assessment of the benefits of roof albedo and thermal emittance is complicated by a number of issues (Suehrcke, Peterson et al. 2008):

- Heat flow across the roof surface combines with that due to air temperature differences between the outside and inside.

- Heat flows due to solar absorption and outside-to-inside air temperature differences are variable and influenced by the thermal mass of the roof.

- The solar absorbance of a roof will change with time due to dust and ageing.

- If the roof is shaded the amount of incident sunlight is reduced, which tends to reduce the potential of cool surfaces (Akbari, Menon et al. 2009).

Whilst it is accepted that the albedo of a roof does have an effect on the heat transfer across the roof, measuring roof albedo is not straight forward. Effects such as surface roughness and small impurities in the material can lower the reflectance and albedo of a surface (Berdahl and Bretz 1997).

Despite this, many equations have been derived for quantitatively assessing the effect of roof albedo and infrared emittance on roof temperature and internal building temperature (Levinson, Akbari et al. 2007). Calculations have also been performed to estimate large-scale energy, carbon and cost savings of the widespread implementation of increasing the albedo of roofs. Tools are available for assessing the potential energy reductions such as the Energy Star Roofing Comparison Calculator (US Environmental Protection Agency 2004).

[edit] Potential

The focus of research to date has mostly been into the impacts of changing the thermal properties of a roof surface to improve building comfort or decrease building energy use. However, recently there has been interest on increasing world-wide urban albedos to offset CO2 emissions that contribute to global warming. The high albedo of roofs and paved surfaces have the potential to increase the albedo of urban areas by 10%.

If this was implemented globally across all urban areas, there would be a negative radiative force equivalent to offsetting 44Gt of CO2 emissions (24Gt by roofs, 20Gt by pavements) (Akbari, Menon et al. 2009). Taking the rate that CO2 was traded at in Europe in 2009, (approximately $25/tonne), this offset would be worth $1,100 billion (Akbari, Menon et al. 2009).

Additional benefits from reducing building temperature and energy use include a reduction in peak power demand meaning that fewer power stations are required. In Los Angeles peak cooling demand increases by 3.0% for every 1oC rise in air temperature above 18oC, and across the US, urban heat islands raise air conditioning demand by about 10GW annually (Rosenfeld, Akbari et al. 1995).

There are also secondary advantages to increasing the albedo of urban surfaces. The resulting lower urban temperatures improve air quality and decrease smog in cities. The probability of smog increases by 6% per oC increase in temperature above a threshold of 22oC (Rosenfeld, Akbari et al. 1995). Preliminary calculations show that a moderate change in surface albedo in Los Angeles Basin could reduce smog about around 10%, the equivalent of removing 10 million cars from Los Angeles roads (Rosenfeld, Akbari et al. 1995).

It is for these reasons that in 2009, Professor Steven Chu, President Obama's Energy Secretary made clear his enthusiasm for the widespread implementation of cool roofs (Times Online 2009). However, implementation of heat island mitigation measures such as cool roofs was also a prominent part of President Clinton's Climate Change Action Plan and yet only limited progress was made on the ground (Rosenfeld, Akbari et al. 1995).

Rosenfeld, Akbari et al. (1995) suggest that the costs of increasing the albedo of a city are quite low if performed during routine maintenance. Roofs are typically refinished every 10-20 years and cooler roofing material is either already available or can be developed at very little cost. Additionally, they suggest that light coloured surfaces suffer less damage from daily thermal expansion and contraction. UV damage is also reduced as this is caused by free radicals which interact more strongly the warmer the material. Rosenfeld, Akbari et al. (1995) suggest policy steps to implementing cool surfaces and shade trees, some of which have now been achieved with various levels of success since 1995.

Cool Roof market is forecasted to grow at a rate of 5.5% from USD 20.49 Billion in 2020 to USD 31.58 billion in 2028. The general application of a roof in a building is that it provides protection from natural elements, but rooftops are becoming a significant source of excessive heat.This is leading to the increasing adoption of cool roofs around the world, as they solve the problem of excessive heat through roofs, which make up around 40% of a building\'s surface. It reflect sunlight and absorb relatively lesser heat than standard roofs.

[edit] Other passive cooling systems

Passive cooling involves designing buildings and selecting construction materials in a way that reduces the energy consumption of active cooling systems. There are many passive cooling techniques that can be applied to roofs (Tiwari, Upadhyay et al. 1994):

- Modifying orientation.

- Providing natural ventilation.

- Selecting appropriate roof materials.

- Spraying water to aid evaporative cooling.

- Shading.

- Green roofs.

- Painting roofs with reflective colours.

Tiwari, Upadhyay et al's 1994 paper includes mathematical modelling of these techniques and concludes that evaporative cooling is most effective at reducing incoming heat through the roof if water is easily available. Green roofs also have significant potential as passive cooling systems.

This article was created by --Buro Happold.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Albedo.

- Brown roof.

- Cool paint.

- Designing green and blue roofs.

- Emissivity.

- Flat roof.

- Flat roof defects.

- Green roofs.

- Long span roof.

- Overheating.

- Pitched roof.

- Preventing overheating.

- Rainwater harvesting.

- Solar photovoltaics.

- Solar reflectance index.

- Solar thermal systems.

- The thermal behaviour of spaces enclosed by fabric membranes.

- Thermal comfort.

- Thermal optical properties.

- Types of cool roofs.

- Types of roof.

- Urban heat islands.

[edit] External references

- Akbari, H. (2008). "Evolution of cool-roof standards in the United States." Advances in Building Energy Research.

- Akbari, H. (2009). "Heat Island Publications."

- Akbari, H., R. Levinson, et al. (2008). "Procedure for measuring the solar reflectance of flat or curved roofing assemblies." Solar Energy 82(7): 648-655.

- Akbari, H., S. Menon, et al. (2009). "Global cooling: increasing world-wide urban albedos to offset CO2." Climatic Change 94(3): 275-286.

- Al-Homoud, D. M. S. (2005). "Performance characteristics and practical applications of common building thermal insulation materials." Building and Environment 40(3): 353-366.

- Alvarado, J. L., W. Terrell Jr, et al. (2009). "Passive cooling systems for cement-based roofs." Building and Environment 44(9): 1869-1875.

- Berdahl, P. and S. E. Bretz (1997). "Preliminary survey of the solar reflectance of cool roofing materials." Energy and Buildings 25(2): 149-158.

- Harrison, H. W. (1996). Roofs and Roofing: Performance diagnosis, maintenance, repair and the avoidance of defects, BRE.

- Levinson, R., H. Akbari, et al. (2007). "Cooler tile-roofed buildings with near-infrared-reflective non-white coatings." Building and Environment 42(7): 2591-2605.

- Prado, R. T. A. and F. L. Ferreira (2005). "Measurement of albedo and analysis of its influence the surface temperature of building roof materials." Energy and Buildings 37(4): 295-300.

- Rosenfeld, A. H., H. Akbari, et al. (1995). "Mitigation of urban heat islands: materials, utility programs, updates." Energy and Buildings 22(3): 255-265.

- Suehrcke, H., E. L. Peterson, et al. (2008). "Effect of roof solar reflectance on the building heat gain in a hot climate." Energy and Buildings 40(12): 2224-2235.

- Times Online. (2009). "Professor Steven Chu: paint the world white to fight global warming."

- Tiwari, G. N., M. Upadhyay, et al. (1994). "A comparison of passive cooling techniques." Building and Environment 29(1): 21-31.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. (2004). "Energy Star Roofing Comparison Calculator." Retrieved 06/07, 2009, from http://roofcalc.com/

Featured articles and news

Shortage of high-quality data threatening the AI boom

And other fundamental issues highlighted by the Open Data Institute.

Data centres top the list of growth opportunities

In robust, yet heterogenous world BACS market.

Increased funding for BSR announced

Within plans for next generation of new towns.

New Towns Taskforce interim policy statement

With initial reactions to the 6 month policy update.

Heritage, industry and slavery

Interpretation must tell the story accurately.

PM announces Building safety and fire move to MHCLG

Following recommendations of the Grenfell Inquiry report.

Conserving the ruins of a great Elizabethan country house.

BSRIA European air conditioning market update 2024

Highs, lows and discrepancy rates in the annual demand.

50 years celebrating the ECA Apprenticeship Awards

As SMEs say the 10 years of the Apprenticeship Levy has failed them.

Nominations sought for CIOB awards

Celebrating construction excellence in Ireland and Northern Ireland.

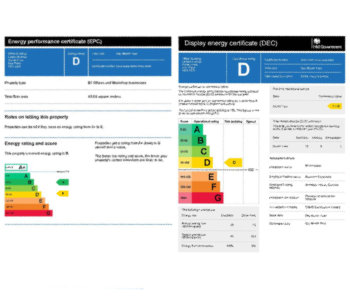

EPC consultation in context: NCM, SAP, SBEM and HEM

One week to respond to the consultation on reforms to the Energy Performance of Buildings framework.

CIAT Celebrates 60 years of Architectural Technology

Find out more #CIAT60 social media takeover.

The BPF urges Chancellor for additional BSR resources

To remove barriers and bottlenecks which delay projects.

Flexibility over requirements to boost apprentice numbers

English, maths and minimumun duration requirements reduced for a 10,000 gain.

A long term view on European heating markets

BSRIA HVAC 2032 Study.

Humidity resilience strategies for home design

Frequency of extreme humidity events is increasing.

National Apprenticeship Week 2025

Skills for life : 10-16 February

Comments

To start a discussion about this article, click 'Add a comment' above and add your thoughts to this discussion page.