Heritage, industry and slavery

With Britain’s industrial heritage such a huge part of its history, when reflecting on the nation’s global significance in the 19th century, interpretation must tell the story accurately.

|

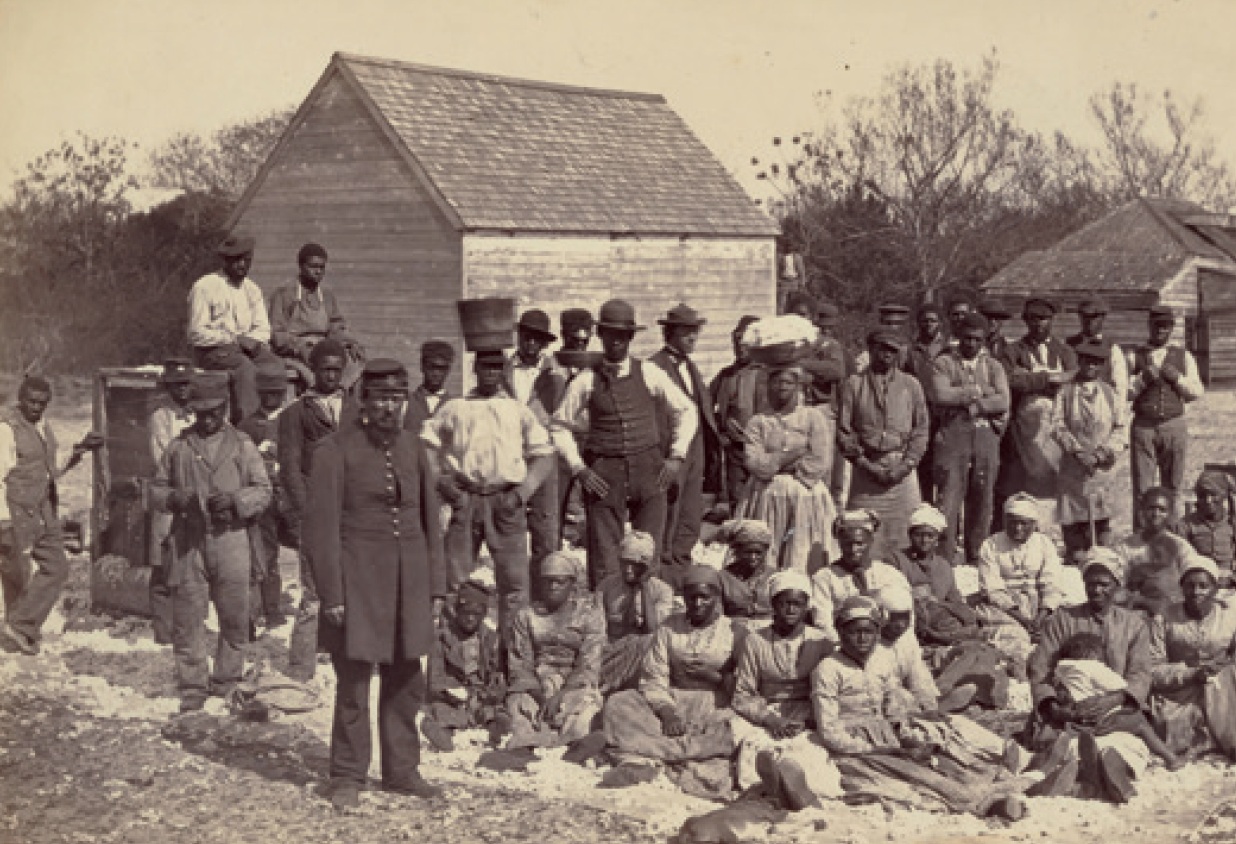

| Slaves of General Thomas F Drayton, photographed by Henry P Moore in 1882. |

What do you make of the following statements? First, railways were not Britain’s gift to the world: they were the world’s gift to Britain. Second, the riches Britons extracted from their slaves in the Americas flowed mainly to a few cities, such as Liverpool, and by the 1830s these places had large numbers of cotton mills. Third, Britain’s railways were financed by the slave trade: slave owners were compensated for the abolition of slavery and these monies were used to fund the building of Britain’s railways.

They are taken from a consultant’s report that crossed my desk a few months ago, from the international business journal The Economist, and from a conversation with a highly educated professional. You may find them surprising, controversial or even counter intuitive. But they are part of a rising tide, seeing events through a new lens, and this may have profound implications for understanding and evaluating our built heritage.

The new lens was first formulated by a young Trinidadian scholar, Eric Williams, in the 1930s. Williams argued that the slave trade stimulated British industry in three ways: slaves were bought with the proceeds from British manufacturers; slave production of sugar, cotton, indigo and molasses created new industries in Britain; the West Indies’ economy provided markets for the North American colonies which, in turn, bought British products. Williams’ book, first published in 1944 [1], was heavily criticised by established historians. Only in the 1960s did his ideas begin to receive attention, especially from some American scholars.

Philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn has referred to this phenomenon as a ‘new paradigm’. Dissatisfied by existing explanations, a young group of researchers invents a new theory which looks at the world in a potentially more enlightening way. But a new paradigm must be tested against the evidence.

Let’s have a closer look at the facts, starting with that reference to Liverpool. It is true that Liverpool slave traders benefited hugely from the profits of the slave trade and doubtless much of this wealth was used to finance shipping fleets, banks, new dock systems and elegant Georgian buildings. It also part-funded the Liverpool to Manchester Railway, the world’s first intercity railway line. Several of the railway’s promoters were slave holders.

But Liverpool was not the only, nor the main, beneficiary of slave-holding wealth, by which is meant the actual ownership of slaves (which may have been a less significant source of wealth than slave trading). The other cities involved were Bristol, Bath and, of course, London, which was by far the greatest centre of slaveholding wealth [2]. There were no cotton mills in any of these places (except for Bristol, which had one). A map provided by The Economist [3] shows that London, Bristol and Liverpool had very small shares of workers employed in manufacturing in 1831. The great concentrations of manufacturing were not the three cities benefiting from slavery, but rather areas of the East Midlands, the West Midlands, West and South Yorkshire, and around Manchester.

Turn to the hypothesis that wealth derived from slavery financed the railways. Slavery was abolished in 1807 and chattel slavery in British colonies ended in 1833, only three years after the opening of the first intercity railway between Liverpool and Manchester. Huge compensation payments were made to slave owners and the detailed record of payments provides a remarkable insight into the geography of slave-holding wealth. There were very low or non-existent levels of slave-holding in the places which produced crucial industrial products and innovations. Railway technology, for example, came from the north-east of England, where the Stockton and Darlington Railway, completed in 1825, is widely accepted as the world’s first railway. There was little or no slave-holding wealth in the North East.

While it seems likely that the great railway construction boom between 1830 and 1860 was financed in part by slavery compensation payments, this was not wealth derived from slavery or slave-holding. It was a transfer of wealth via taxation from all Britain’s taxpayers to the small group of former slave owners. Recipients could spend the money as they wished, though doubtless some of the monies went into the great railway-building boom. But the suggestion that railways were the world’s gift to Britain, financed by the exploitation of workers in other countries, does not seem to hold water. Railways, like our industrial heritage as a whole, were financed by the exploitation of the British and in-migrant working classes who were paid a pittance for working in the mills, down the mines and in the steel works.

American academic Joel Mokyr is the world’s leading economic historian of the Industrial Revolution. He has devoted a lifetime’s thought and research to the subject [4], arguing that intellectual rather than material factors were the driving force behind the Industrial Revolution, with one important exception. Before 1780, most of the cotton coming to Britain came from the West Indies. The explosive growth of Britain’s cotton industry came to depend on the south of the USA. ‘Simply put,’ writes Mokyr, ‘without United States slave labour it is hard to see how the tremendous growth in demand for raw cotton could have been satisfied... It is here and not in the consequences of the [British] eighteenth-century triangular trade that slavery really mattered for the Industrial Revolution.’

British economic historians Maxine Berg and Pat Hudson have scrutinised the available evidence on slavery and the Industrial Revolution. Their book provides a carefully balanced account [5] which is essential reading for those who want to get to the bottom of this controversy. The depth to which slavery influenced Britain’s economy is certainly striking. In the prosaic words of John Carey, a Bristol sugar merchant speaking in 1712: ‘The African Trade is a Trade of most Advantage to this Kingdom... for we have in return Gold Teeth [ivory], Wax and Negroes, the last whereof are much better than the first, being indeed the best Traffic the Kingdom hath.’

African slaves were essential to the sugar plantations, to the wealth generated by the sugar trade and thus to changing patterns of consumption. Surprisingly remote places were involved. Britain’s mining and smelting industries were stimulated by the Atlantic trades. Copper from Cornish mines was used to build vats for boiling sugar cane in the West Indies. Of huge importance was the extraordinary impact of the sugar trade on the growth of finance and banking, especially in London. Credit and payment systems evolved, involving the use of traded ‘bills of exchange’. All this laid the foundations for London’s role as an international financial centre, rather than the backer of unschooled provincial manufacturers.

Berg and Hudson do not push their analysis beyond the evidence. They accept that if slavery alone explains the Industrial Revolution, it is hard to understand why Spain, Portugal, France and the Low Countries were not industrial leaders. Clearly other factors were at work. There is, they accept, little hard evidence on the flow of investment funds from slavery to the textile industry. Liverpool’s slavery compensation monies seem to have flowed mainly into shipping, insurance and banking – the pursuits of the gentleman capitalist. And their maps continue to pose a dilemma. Evidence on the regional distribution of textile employment shows massive concentration in Yorkshire and West Lancashire, and absolutely no textile employment around London, Bristol and Liverpool. Such as it is, the geographical evidence suggests a continuing divide between the slave owners, traders and financiers, and the industrialists and inventors.

Does it matter? When I discussed this with a New Zealand friend, she wondered if it was more evidence of a country locked into the past and not looking to the future. I would have to disagree. Industrial heritage is a huge part of Britain’s history, reflecting the unparalleled global significance of Britain in the 19th century. No less than a third of our world heritage sites have a direct connection with the Industrial Revolution and mitigating its worst features. To do the job properly, interpretation must accurately tell the story of how the heritage arose, within the limits of available evidence. That is the point: we must not allow speculation to replace evidence.

There is one other critical reason for examining the past, including the less-than-benign elements that we might rather forget. Only by genuinely understanding history can we shake off our illusions of unblemished greatness, understand the racism that pervaded the British empire, re-evaluate our hugely expensive ‘world role’ (we are still the world’s third biggest military spender), and begin to set a new, perhaps diminished, but ultimately more humane course for the future.

References:

- [1] Eric Williams (1944, reissued 2022) Capitalism and Slavery

- [2] UCL Legacies of Slavery Database

- [3] Economist (2023) ‘Mother of Invention’, 21 January

- [4] Joel Mokyr (2009) The Enlightened Economy

- [5] Maxine Berg and Pat Hudson (2023) Slavery, Capitalism and the Industrial Revolution

This article originally appeared in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 180, published in June 2024. It was written by Ian Wray, professorial fellow at Manchester University’s planning school.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Conservation.

IHBC NewsBlog

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.

National Audit Office (NAO) says Government building maintenance backlog is at least £49 billion

The public spending watchdog will need to consider the best way to manage its assets to bring property condition to a satisfactory level.

IHBC Publishes C182 focused on Heating and Ventilation

The latest issue of Context explores sustainable heating for listed buildings and more.