Village homes in Western Uganda

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Mark Harry, MCIAT, shares his account of a trip where he stayed within the confines of Kishenyi Village, Western Uganda, which is 7km from DR Congo and close to Queen Elizabeth National Park.

[edit] Traditions associated with building a home

It is traditional within the locality that when the son of a family is to get married a parcel of their parent’s plot is given to him. This is where he can build his own house for his family.

There are two main types of houses built within the village. The first built from bricks and the most common is built from timber with mud infill. Both types are single storey only.

[edit] Type 1: Brick built

The bricks are made on site. There is a local quarry where all the locals go to buy clay to make their bricks, pots, earthenware etc. When making bricks, it is common practice to add earth to the clay so that extra bricks are made and keep the cost to a minimum.

The earth where I stayed was quite sandy. A timber mould could make two bricks at a time. It was then emptied out onto the earth, and after a few hours it was carefully taken onto a stack to cure with protection from the rain on the top. Temperatures were a constant 24 degrees.

Brick built houses had a plastic dpc at floor level. There were a few brick houses that were finished with smooth render, plaster inside and tiled floor – very few, but they were there!

There was no water supply within the village, so all water was collected in Jerry cans at a local source.

[edit] Type 2: Timber frame

Unless you had money, this was the main type of house built.

The person I had most dealings with was Gumi Onnissmus. He was in the middle of building his own house in a timber frame on his Mum’s land. It was typical to build as - and when - money came along. It can take quite a few years to finish off a house!

The size was 6m x 5m x 2.5m to eaves. The shell and roof had already been completed. It was made from a framework of straight branches (approximately 75mm dia at 600 mm centres) and infilled with sand/earth and clay.

There are horizontal bamboo canes every 24” (600mm) to support the earth/clay infill on both sides of all walls. The bamboo canes and timber framework are fixed and held together with banana fibres – no string. The roof set at 20 degrees is clad with steel corrugated sheets with eaves overhang about 30” (762mm). Eaves were about 2.5m high.

The roof structure was from branches in traditional rafter spacings with a few ceiling ties. A central timber strut came down on the centre wall. The walls are approximately 125mm wide.

Gumi had dug out a pit latrine about 15’-0” (4.5m) deep situated about 20’-0” (6m) downhill from the house. I asked Gumi how deep the pit must be, and he said he was going to take it down 20’-0” for it to last two years. Then, when full, he would dig another one.

Gumi’s house will have two bedrooms, a sitting room and a dining room.

Each room had a window, and above each there was an opening for vents to be installed. The vents were a fine metal insect mesh on the inside to stop mosquitoes entering with a vent to each gable.

To render the outside walls, Gumi mixed the earth/clay with some ash to give a better protection against the weather.

All the houses that I entered had an earth floor. The children sat and ate their food on a raffia mat while the grown-ups sat at the table.

There were no ceilings but exposed roof timbers. In addition, there was no water and no electricity. Lighting was a small oil filled lamp that gave a background light. After tea, which was about 21:00, the family would sing and the children dance.

There were no doors on the inside - just a curtain to each door opening. This was typical to all the houses that I visited.

Everyone within the village had a separate building for their kitchen. It was mostly built from bricks (but not always). Rocks were placed on the floor and a fire made from wood, sticks, branches etc. between the rocks. Saucepans went onto the rocks. Some kitchens used pieces of termite hills instead of rocks to hold their saucepans, because it remained a lot cooler due to the ventilation holes through the (fired) pieces. Kitchen sizes were approximately 1.2m wide x 2.4m long with a steel corrugated roof. Above the fireplace at approximately 1.7m high was a timber framework that was used to dry out banana leaves, banana fibres and anything that would be damp.

Outside the kitchen everyone had a two-tier timber framework (from branches) approximately 1.2m high and a shelf below x 1m x 1.5m. This was used to place the saucepans out to dry after washing them clean. It was also common to put down a few banana leaves first on the framework.

During my two weeks stay it rained quite frequently. I did not see (or smell) any damp in any house that I entered. Even though it rained, the sun came out; within an hour, all was dry again.

This article originally appeared in the Architectural Technology Journal (at) issue 133 published by CIAT in Spring 2020. It was written by Mark Harry MCIAT, Chartered Architectural Technologist.

--CIAT

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

Statement from the Interim Chief Construction Advisor

Thouria Istephan; Architect and inquiry panel member outlines ongoing work, priorities and next steps.

The 2025 draft NPPF in brief with indicative responses

Local verses National and suitable verses sustainable: Consultation open for just over one week.

Increased vigilance on VAT Domestic Reverse Charge

HMRC bearing down with increasing force on construction consultant says.

Call for greater recognition of professional standards

Chartered bodies representing more than 1.5 million individuals have written to the UK Government.

Cutting carbon, cost and risk in estate management

Lessons from Cardiff Met’s “Halve the Half” initiative.

Inspiring the next generation to fulfil an electrified future

Technical Manager at ECA on the importance of engagement between industry and education.

Repairing historic stone and slate roofs

The need for a code of practice and technical advice note.

Environmental compliance; a checklist for 2026

Legislative changes, policy shifts, phased rollouts, and compliance updates to be aware of.

UKCW London to tackle sector’s most pressing issues

AI and skills development, ecology and the environment, policy and planning and more.

Managing building safety risks

Across an existing residential portfolio; a client's perspective.

ECA support for Gate Safe’s Safe School Gates Campaign.

Core construction skills explained

Preparing for a career in construction.

Retrofitting for resilience with the Leicester Resilience Hub

Community-serving facilities, enhanced as support and essential services for climate-related disruptions.

Some of the articles relating to water, here to browse. Any missing?

Recognisable Gothic characters, designed to dramatically spout water away from buildings.

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

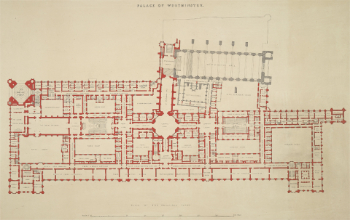

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.

Comments

The timber frame usually doesn't take along time to complete since the materials are sourced locally only parts that need manufactured ones are roof(if they don't use grass thatch) and the few number of windows and normally one exit door. The other thing is the reeds (lateral support structure) to hold in place the wet mud-which sometimes is mixed with straw.

Thanks for the comment, sounds like you have personal experience, I will leave it as a comment here. Best