Sustainability rather than sentimentality in the refurb sector

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Every generation tries to improve on what went before, often by denigrating the past as old fashioned and out-dated. In the construction sector, that axiom has led to some tragic destruction of our architectural heritage. Crafted features, such as joinery, fireplaces, architraves and tiling, have been covered over or ripped out, to be replaced with alternatives that have not stood the test of time well in terms of either quality or aesthetics.

It is a sad history of allowing transient trends to damage our architectural heritage that has now, thankfully, been addressed both by designers and construction professionals who respect the artisan builders of the past; and by heritage and conservation rules. Where a building is listed or located in a conservation area, there are strict limits on what changes can be made, which vary depending on the type of listing and local heritage stipulations. This, quite rightly, protects features that are unique or unusual; but not everything that is being protected in the name of heritage really warrants such vociferous protection. Sometimes, keeping an original feature or material, or being required to replace it on a like-for-like basis, actually conflicts with the aim of extending the lifespan of the building and fails to consider the net carbon zero agenda.

[edit] Preventing sympathetic refurbishment

There are 350,000 Grade II listed buildings in the UK, which, along with the conditions of local conservation areas, means we have a huge volume of properties that cannot benefit from upgrades to the building fabric in order to become more energy efficient, more comfortable, more robust and more suited to the needs of today's occupiers.

In an effort to rectify the mistakes of the past and prevent any further loss of our architectural heritage, has the pendulum now swung too far in the opposite direction? Are we at risk of actively discouraging the sympathetic refurbishment of heritage buildings?

Sadly, the answer to that question is sometimes yes. Onerous heritage requirements often mean potential refurbishment projects fall at the first hurdle because they are simply not viable. The costs can escalate, materials can be difficult to source, and, in some cases, the required outcome is simply not achievable because of restrictions on remodelling and upgrades to thermal performance. The designer, the developer and the construction company may want to do everything they can to protect the building's original design and building fabric, but the project also has to work commercially, otherwise a developer simply cannot take it on.

And alongside the properties that are slowly slipping into dereliction because heritage-compliant restoration is too complex and expensive, there is also an issue of developers choosing to side-step the system. With just a little more pragmatism on the part of heritage officers and conservation regulations, we would be able to avoid both of these scenarios by encouraging collaboration between design and construction professionals and the heritage community to deliver commercially viable outcomes that are best for both the building and the environment.

[edit] Pragmatism in practice

So how would a more pragmatic approach to refurbishing old buildings work in practice? If the rules were applied as principles rather than with a monochrome approach to permitted or not permitted, perhaps we'd be better able to do what's right for each project and each building, rather than aiming for a tick in a box.

Hale's own offices in Surrey provide a useful example. A Grade II listed building, our offices have undergone various modifications down the decades when the property was owned by others and before the heritage requirements were put in place. As a result, many of the original features have already been removed and the interior bears little resemblance to what the building would have looked like when first constructed.

As part of a recent refurbishment, we needed to replace an existing staircase and the heritage officer was pragmatic in allowing us to install a new replacement rather than rebuilding the old staircase. However, he stipulated that the stairs needed to start and end in the same location within the building, making it impossible for us to remodel the space in a more efficient and user-friendly way for our business.

More frustratingly was the stipulation that we would need to change the sliding sash windows that were replaced by the previous occupier. Whilst these were traditionally-made timber sliding sash windows, they were double glazed and we were instructed to replace them with single glazed, using putty. This seems ridiculous given the current climate crisis – and also that the windows are good quality and no more than 10 years old. Single glazing not only encourages heat to escape during the winter, driving up our heating bills and carbon footprint, it also leads to condensation, which could result in issues with damp and mould.

As a construction company with a considerable track record in heritage refurbishment, we know that it is possible to achieve an installation that looks virtually identical to the original, while enhancing the building for the future – but cumbersome heritage rules do not allow for this.

[edit] Streetscapes without compromise

Heritage is not only about protecting individual features and buildings; it is also about protecting traditional streetscapes. We are very fortunate in the UK to have such a wealth of architectural heritage and many of our high streets are very geo-specific, articulating the history of a town and how, where and why it was built. But maintaining the streetscape does not have to mean keeping the buildings exactly as they have always been. The important factor is preserving the appearance from the street, what lies behind should have the potential for modification to meet the needs of new occupiers, new technologies and the climate crisis.

For example, if the building has limited headroom on the ground floor, why should we not be permitted to lower the floor to provide more suitable accommodation? This would also allow insulation to be installed as part of the floor build-up, alongside suitable interior wall insulation and aesthetically appropriate double or triple glazing. All of this could be done in a manner that allows the building to look the same from the outside, and very similar from the inside, but instead of being pokey and draughty, the ground floor would become user-friendly and thermally efficient, preserving it for a new generation of use.

[edit] Living history

We have historic buildings that need to be protected as museum pieces due to their importance, but most heritage buildings are simply remnants of a bygone era, and our goals should be to ensure they remain in use. We might want to keep every tile and every cornice, but if the tiles are laid on uninsulated floors and the cornices decorate lathe and plaster walls that were never built to last this long, we are not really protecting the building; we're allowing it to decay.

To be functional in the 21st century, buildings need electrics, lighting and data, and the irregularity of old walls and joists is often incompatible with those services because they simply did not exist when the property was built. So, instead of hanging on to sentimental ideas of heritage, let's ensure that our architectural heritage survives by updating it and working with it, rather than being a slave to the past.

Article appears in the CIAT news and blog site dated August 18 entitled "Is it time to swap sentimentality for sustainability in the refurb sector?"

--CIAT

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

Featured articles and news

ECA digital series unveils road to net-zero.

Retrofit and Decarbonisation framework N9 launched

Aligned with LHCPG social value strategy and the Gold Standard.

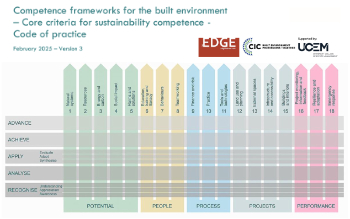

Competence framework for sustainability

In the built environment launched by CIC and the Edge.

Institute of Roofing members welcomed into CIOB

IoR members transition to CIOB membership based on individual expertise and qualifications.

Join the Building Safety Linkedin group to stay up-to-date and join the debate.

Government responds to the final Grenfell Inquiry report

A with a brief summary with reactions to their response.

A brief description and background to this new February law.

Everything you need to know about building conservation and the historic environment.

NFCC publishes Industry White Paper on Remediation

Calling for a coordinated approach and cross-departmental Construction Skills Strategy to manage workforce development.

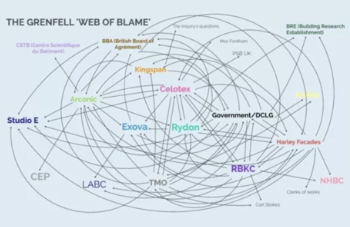

'who blames whom and for what, and there are three reasons for doing that: legal , cultural and moral"

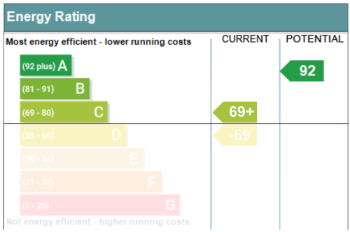

How the Home Energy Model will be different from SAP

Comparing different building energy models.

Mapping approaches for standardisation.

UK Construction contract spending up at the start of 2025

New construction orders increase by 69 percent on December.

Preparing for the future: how specifiers can lead the way

As the construction industry prepares for the updated home and building efficiency standards.

Embodied Carbon in the Built Environment

A practical guide for built environment professionals.

Updating the minimum energy efficiency standards

Background and key points to the current consultation.

Heritage building skills and live-site training.

Comments

I can't understand how it would be acceptable to demolish an original staircase to rebuild it just in the same location. And then replace double-glazed windows for single glazing. It makes no sense.

Either there is some 'lost in translation' or this is a rare case scenario. I don't think conservation officers usually work on such random principles.