Preventing wall collapse

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Free-standing walls which front onto streets, paths, yards or gardens or walls within buildings should be carefully monitored to prevent dangerous collapse. Vulnerable walls are those that appear to be very slender, those which are loose, those that have different soil levels on each side, those that lean, and those where there are signs of damage or deterioration.

There have been numerous instances of collapses and a number have resulted in fatalities and injuries.

When walls collapse they tend to fall as slabs of masonry which break up on contact with the ground. Irrespective of the force causing the collapse if a person is between such a slab and the ground, and particularly if the person is shorter than the height of the wall, then they are subject to a traumatic blow which can be fatal.

It is well known that many freestanding walls are often poorly constructed and not adequately maintained.

Outside the UK, the situation is similar and there are press reports from many countries when falling walls have proved fatal. Where there is seismic activity the consequences are much worse and simple masonry walls can cause huge losses of life as they succumb to the effects of earthquakes.

[edit] Building regulations

Under current England and Wales Building Regulations Part A there is no requirement to submit designs or drawings for new free-standing walls or retaining walls unless these provide lateral support to the foundations of another building.

If a boundary wall is a retaining structure but not directly associated with a building then it does not come within the requirements of these Regulations. A Circular Letter was issued to all Building Control bodies in England and Wales in 2013 from the Department of Communities and Local Government (CLG) reminding them of the dangers of freestanding and retaining walls.

The CLG Planning Portal also advises on the need for planning permission for walls higher than 1m adjacent to a highway and on safety matters.

In Scotland, freestanding walls are subject to building regulations, and in the most part would require a building warrant - Building (Scotland) Regulations 2004.

If it can be shown, or suspected, that an existing wall is dangerous then a Local Authority (LA) in England and Wales has powers under the Building Act to take action but has no duty to identify them. One suggestion is that dangerous free-standing walls should be defined as 'Statutory Nuisances' making it a duty for LA’s to inspect their area and take action by issue of statutory notices.

In addition, the various statutory duties under the Health and Safety at Work Act, and other associated legislation, always apply if the actions are associated with a work activity. In essence this means that those creating the risk by designing and/or creating the wall have a duty to safeguard anyone who may be affected by their actions. Importantly for retaining walls within ‘4 yards (3.7 m) of a street’, section 167 of the Highways Act 1980, requires the retaining wall to have approval from the local authority.

If this is an adopted public highway, it is a matter for the Highway Authority, which may not be the Local Authority.

[edit] Guidance

[edit] Inspections of existing walls

There are thousands of kilometres of free-standing walls in the UK and it is impractical and indeed unnecessary to inspect them all. However, a risk assessment can be helpful in determining which walls merit attention. The risk of a wall causing death or injury depends upon its location in relation to people.

If children are habitually in the vicinity this must be taken into account because of their height in relation to the size of wall. If a wall adjoins a pavement or public footpath its condition is more sensitive than if were between fields in a remote country area. However, there are walls in rural areas that can be dangerous, for example dry stone field walls are increasingly crossed as Right to Roam means walkers stray from footpaths. Weathering and deterioration are obvious factors. Vulnerability to impact or other lateral load, whether accidental or deliberate, must also be considered.

The ownership of walls may need to be clarified both at the design stage and in-service. Even major asset owners may not agree about ‘demarcation of responsibilities’. If you are not sure who owns, then who inspects?

It can be difficult to see whether a wall is defective enough to be dangerous. Nor is it easy to comprehend that a low wall can become a deadly instrument.

A long term campaign is needed to inform and educate those who build such walls without engineering advice which is often the case with walls that fail. Even if the wall has been properly designed and built such structures degrade due to environmental actions, such as the presence of tree roots, as well as by simple ageing.

A wall which was safe as constructed will eventually become unsafe. Other walls, particularly masonry retaining walls, can be inherently dangerous from the day of construction if there has not been proper design input.

General points to look for when inspecting a wall include the following, although these are by no means exhaustive:

- Alterations, such as additions to the wall or removal of adjoining structures.

- Change of use.

- Obvious movement or rocking when pushed.

- Surface crumbling.

- Condition of mortar pointing.

- Cracking.

- Effects of nearby trees.

- Verticality.

- Surcharge, filling or excavation on one side.

- Settlement.

- Height to thickness ratio.

- Walls higher than 1.7m.

- Security of cappings.

- Changed exposure conditions.

- Frost and water damage.

- Impact damage.

- Damage from traffic.

- Damage from climbing plants.

- Poor repairs.

In many cases, an inspection using these points as a check list coupled with basic building knowledge should give some reassurance. If a wall is greater than about 1.7m, then it should have been designed by an engineer in the first place. If the basis of design for a wall of this or greater height is not known or there are significant defects or points of concern then advice should be sought from a suitably experienced structural engineer.

The assessment of whether defects are significant depends upon their extent and possibly on a combination of effects. A wall is obviously unsatisfactory if it is retaining material yet its proportions are only those of a simple garden wall. It would also be unsatisfactory if there was evidence of movement or overall looseness such that a modest lateral force could precipitate collapse.

Even if a wall is found to be in good condition, inspections should be repeated at intervals because deterioration is inevitable and circumstances may change. Records of inspections should be kept. Free standing brickwork or blockwork may form parapets and if not properly designed, particularly on old or poorly maintained buildings, may be prone to collapse.

[edit] Design of new walls

There are a number of sources of information on the design and construction of walls and anyone responsible for such a structure should ensure that such guidance has been followed. British Standard BS 5628, Code of Practice for the use of masonry which was the standard for many years has been superseded and replaced by Eurocode 6 and PD6697.

The Brick Development Association Design of free-standing walls continues to provide detailed guidance on the subject. Empirical rules are given in garden walls including minimum thicknesses for walls of different heights in various areas of the UK depending upon zones of wind strengths.

The most important design criterion for engineered free-standing walls is likely to be wind loading.

Any retaining wall can be dangerous and it is recommended that they should always be designed by a competent structural engineer. There are also risks for designers and contractors, particularly on site, during construction. Where a wall is safe in its permanent condition it may be subject to more adverse temporary loads during construction and contractors should be aware of what they are building and the Temporary Works Co-ordinator should review temporary situations which may impact on short term stability.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Cracking and building movement.

- Defects in brickwork.

- Defects in construction.

- Defects in stonework.

- Diaphragm wall.

- Movement joint.

- Party wall.

- Responsibility for boundary features.

- Retaining walls.

- Shoring.

- Temporary works.

- Ties.

- Underpinning.

- Wall tie failure.

- Wall ties.

- Wall types.

- Why do buildings crack? (DG 361).

Featured articles and news

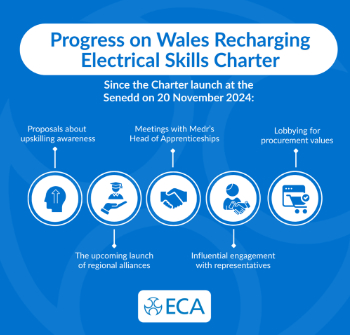

ECA progress on Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter

Working hard to make progress on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.

Many resources for visitors aswell as new features for members.

Using technology to empower communities

The Community data platform; capturing the DNA of a place and fostering participation, for better design.

Heat pump and wind turbine sound calculations for PDRs

MCS publish updated sound calculation standards for permitted development installations.

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.