The Improved Public House

In the years following the first world war an entirely new public house type developed: the Improved Public House used some radical design principles to regulate alcohol consumption.

|

| The Comet, Hatfield (1934, Grade II), designed by EB Musman. Photo by John East. |

Contents |

Introduction

The hub of the community and the social heart of a place; public houses are rarely noticed until they are threatened or lost. Prominent landmark buildings of today, they are the result of the attitude of successive generations to drink and community. Most traditional pubs have evolved, changing as the years pass but rarely the result of a single reasoned design. But in the years following the first world war an entirely new public house type developed. Becoming known as the Improved Public House, it used sometimes radical design principles to incorporate contemporary ideas on the regulation of alcohol consumption.

Before the first world war

During the 19th century the growing population became increasingly urbanised. In these rapidly growing urban areas new types of licensed premises developed. The most showy and flamboyant of these were the gin palaces, gleaming with their elaborate carved furniture and etched mirrors. Beerhouses were smaller domestic establishments whose licence permitted them only to sell beer. Street-corner beer houses were considered to be a haunt for those of ill repute, and the cause of disorder and immorality. In a life beset with overcrowding, malnutrition, polluted water supplies and poor sanitation, it may be little wonder that the slum populous took refuge in drink and turned to the pub as the societal heart.

The local licensing justices rarely allowed alterations or rebuilding of existing premises or the creation of new licences, believing that new or improved premises would encourage more drinking and drunkenness. As a result very few pubs were rebuilt before 1914.

Traditional village taverns had three public rooms: a public parlour, a tap room and a bar. Alongside their saloon and the public bar the new 19th century outlets began to introduce more and more rooms. By the 1890s some had as many as 15 different areas.

The brewery companies, concerned by the economic situation after the Boer War, set about acquiring, en masse, free houses within their areas of operation. In 1880 12,000 pubs brewed their own beer. By 1914 this had fallen to 1,500 and 95 per cent of public houses were in the hands of the breweries. Even when beer sales were low, the brewers’ share in the market was maximised through their tied houses. Small breweries had been driven out of production and the expanding brewing empires had inherited premises which were often dilapidated, decayed and unfit.

The Licensing Act 1902 gave the police power to arrest drunks and prohibited the sale of intoxicants to known drunkards. The act also reinforced the relationship between licensing and the physical form of licensed premises. Justices were required to maintain the standards in the legislation, and to approve alterations and architectural drawings before a licence could be granted. The action of the magistrates under the 1902 act led to the closure of many sub-standard premises but their local power, and often strong temperance links, largely prevented the improvement or redevelopment of public houses.

Sometimes known as the Brewers Burial Act or the Balfour Act, the Licensing Act 1904 provided compensation for premises whose licences were removed as a result of action by the licensing justices. Thousands of pubs were closed as a result. The money to pay the compensation came from the trade itself by a payment known as ‘monopoly value’, demanded of the brewer when a new licence was granted. The 1904 act led to a bargaining situation between breweries and magistrates to close smaller pubs if a larger one were to be built. Brewing companies which bargained were able to open houses in areas of potential development. These new developments in expanding, often suburban, areas became the trial grounds for a new approach to public house design in the years between the wars.

The wartime government of the first world war was concerned about drunkenness in the workforce. The prime minister, David Lloyd George, announced that ‘we are fighting Germany, Austria and drink, and… the greatest of these deadly foes is drink’. Legislation was introduced in an attempt to curb the problem, which was considered particularly dangerous among munitions workers. The Defence of the Realm Act 1914 restricted beer production and encouraged a reduction in the strength of beer. The sale of certain types of strong drink was prohibited, new restrictions on opening hours were introduced and the act even prevented pub customers from buying each other drinks.

The Carlisle experiment

The influx of 30,000 war munitions workers into rural Cumberland led to a sharp increase in the number of convictions for drunkenness. In response, in January 1916 the government took over all breweries and licensed premises in and around Carlisle, acquiring five breweries and 321 public houses. Similar state ownership took place at Enfield Lock and the Cromarty Firth.

One hundred and thirty pubs were soon closed and those which survived were often radically altered. Small rooms and snugs, which could not easily be supervised by the management, were removed, as remaining pubs were gutted internally. Although much of the improvement was confined to the alteration of existing buildings, some new pubs were built. These differed considerably from those of the 19th century, being large and spacious, without small rooms and compartments, and providing the customer with distractions from drink, such as billiard tables and bowling greens. Many innovations and introductions were made to the plan and design of the new buildings.

The architect to the Central Control Board (Liquor Traffic) was Harry Redfern. His 14 New Model Inns were designed in an arts-and-crafts style. Today New Model Inns (Apple Tree, Andalusian, Magpie, Cumberland Inn, Spinners Arms, and Horse and Farrier) and remodelled houses (Crown Inn, Globe Tavern and Near Boot Inn) are all listed Grade II. Regarded as experimental, the Carlisle houses were studied with interest by potential pub designers elsewhere.

The Improved Public House

At the end of the war brewers and magistrates alike began to reassess the public house trade. Brewers, plotting their economic route into the next decade, were eager to expand into the new estates and on to arterial roads. Magistrates, heartened by the Carlisle experiment, wrested with their moral consciousness and were at last prepared to consider building new pubs. Some magistrates, like those in Birmingham, saw very soon after the war the potential benefit from moving pubs from congested urban sites to those where there was greater scope for improvement.

Characteristically, the new Birmingham pubs, built mainly for Mitchell and Butler, Ansells and John Davenport, were enormous premises in roadside locations and evolved the basic rules of ‘improved’ internal layout and plan. The huge Brewers Tudor Black Horse, Northfield Birmingham (1929, Grade II*) by Francis Goldsbrough is an important surviving example of these Birmingham pubs, and indeed one of the best of the period. It combines, as the list description says, ‘careful planning, authentic construction, imaginative design and inspired craftsmanship’.

Very soon the Birmingham ideas were being implemented and adapted countrywide. As towns and cities expanded into the growing suburbs and the use of vehicles increased, brewers saw the potential to revive the notion of the coaching inn and wayside halt. Large and impressive public houses, built on arterial roads, came to be known as roadhouses. They featured dance halls, tennis courts, golf courses and swimming pools. The first roadhouse, the Ace of Spades, was built in 1928 on the Kingston bypass. The restaurant, seating 800, served food 24 hours a day, and the pub had a miniature golf course, an open-air swimming pool, a riding school, a polo ground and an air strip. Only remnants survive today after a fire in the 1950s. Roadhouses were short lived and fell out of favour very quickly. Those few which survive are much altered and most have been redeveloped entirely.

The influence of the true roadhouse, with its dance halls and swimming pools, was soon felt in provincial towns and cities. Without the elaborate facilities many were simply large pubs, but these commodious buildings, with spacious roadside sites and impressive, prominent appearance, had the aspirations of the roadhouse. New pubs were built on the network of major roads growing around the edge of towns and on village bypasses. EB Musman’s design for the famous Comet, Hatfield, on the Barnet bypass (1936–8, Grade II), is thoroughly of the 20th century, with pioneering style and horizontal emphasis. Many pubs were built in the suburbs or roads just out of town, but some, like the Prospect, Minster on Thanet, by Oliver Hill (1939, Grade II), on a road approaching the Kent coast holiday resorts, took advantage of views of the countryside.

Morals and aesthetics

Architectural pub design was governed as much by morals as by aesthetics, with magistrates seeking simple, undecorated designs which were very different to the gaudy ostentation of the gin palaces. It was important to brewers that the building looked welcoming but most of all that it looked like a pub. Here was the challenge to the architect to produce a new type of building in a style befitting its new moral status. Some influential architects were able to rise to the challenge. Others failed and floundered in a quagmire of pastiche.

Stylistically most of the Improved Public Houses harked back to traditional styles (Old(e) English(e), Tudoresque, Brewers Tudor, vernacular revival and neo-Georgian), with some few pushing the boundaries of modern. Old English was representative of the traditional country inn which, unlike alehouses and gin palaces, were still considered respectable and hospitable. It is the style easiest to criticise, with its retrospective attitude and jingoistic use of imagery, but it epitomised the temper of the age: the need to escape from the fear of war and economic depression to something known and comfortable.

In the 1920s a widely used vernacular revival developed for public houses. The roughcast walls, low, sweeping, graded slate hipped roofs, haphazard chimneys and large dormer windows create the visual effect more of a medieval manor house or an overblown barn than a pub. The crucial aim was that they looked rural even when located in the midst of an urban area. Brewers Tudor, with its half-timbered gables, machine-straight blackened beams, oak doors with Tudor arches and bottle glass windows, was safe and acceptable. It sat well along arterial roads, where it was surrounded by houses built with the same Tudoresque notions.

The romantic view of coaching inns which developed in the 1930s made neo-Georgian a favoured style. It was especially but not exclusively used on more confined urban sites. It was sometimes called ‘Post Office style’ because it was so similar to the regimented symmetry, plain brickwork and precise arches used by the GPO in its interwar offices for expanding town centres. Contemporary literature often used words such as dignity and restraint to describe the neo-Georgian, the apogee of the moralistic approach to pub design. The use of sash windows was often rejected by licensing magistrates, who considered them old fashioned and were suspicious that they could be lifted easily at the bottom for illicit purposes. If permitted, they were often only used on the upper floors. The Test Match, West Bridgford, Nottingham (1937, Grade II*) by AC Wheeler has the appearance of a Georgian country house, break fronted and symmetrical, and it unusually has sash windows throughout. The Test Match is most notable for its surviving surprising art-deco interior plan and fittings: a two-storey lounge, terrazzo floor, sweeping staircase and first-floor cocktail bar.

The later inter-war years saw the development of a modern style quite specific to public houses, often with horizontal steel windows and curved forms inside and out, from the building itself to the bar inside. But the truly modern public house remained a much publicised and highly acclaimed novelty. Brewers, who were reticent to spend money on any style but Tudor, found it unsuitable, ‘too arid to be either comfortable or homely,’ said EB Musman, an architect who had already been successful in persuading the use of a more radical design.

Musman, one of the most famous exponents of modern design in public houses, was responsible for the Comet, Hatfield (1934, Grade II) and the Nag’s Head, Bishop Stortford (1935, Grade II). Few architects were able, like Musman, to grasp enough elements of modernism to produce buildings which were restrained enough to win the approval of magistrates and homely enough to win customer support, while having sufficient design flair to create a new style that did not rely on pastiche. The Ship Hotel, Skegness (1934, Grade II), a seaside pub by Nottingham architects BE Bailey and E Eberlin for the Home Brewery, has an appropriately nautical style in ocean-liner art deco. Steel framed with horizontal emphasis and metal casements and a flat roof with cantilevered eaves, it is topped, in the style of a ship’s deck, by a steel balustrade.

As a new approach to the plan and facilities of pubs developed, this Improved Public House, with its enlarged interior spaces, outdoor amenities and provision of food and light refreshments in dining or tea rooms, began to be seen as a solution to the immorality of drink. The renaissance of the public house as a place, no longer just for drinking, but for social and leisure activity, removed some of the stigma and attracted new customers in the middle classes and aspirational working classes. Women were encouraged and children’s rooms provided. These new customers were seen in turn by the magistrates as a potentially sobering influence on the drunken rabble.

Brewers became aware that although alterations to existing pubs with larger rooms, minimum counter lengths, adequate toilets and areas for food consumption would meet the requirements of the magistrates, demolition and elaborate rebuilding on the site would make an impression on the new customers they wanted to attract. In 1936 the Home Brewery in Nottingham proposed conversion of a late Victorian house, the Corner House, into a pub. By 1937 they had abandoned this plan and commissioned local architect Cecil Howitt to design on the same site the Vale Hotel, Daybrook, Nottingham (Grade II) a modern prestigious property that explored the full potential of a crossroads location on a main arterial route.

The breweries began to invest large sums in improving or rebuilding their properties and saw the commercial potential in courting the moral mood of the age. The Home Brewery in Nottingham spent £500,000 between 1918 and 1936 on redevelopment of its stock. Conservation and historic significance were not major considerations with the development of the Improved Public House. Many old and historic premises, especially villages pubs, were demolished.

Larger rooms were visible from a central bar to prevent the immorality and lascivious behaviour associated with the private bars and small snugs of Victorian premises. In 1938 EB Musman advocated there should be ‘no alcoves or portions screened off in which customers can carry on betting or other practices prohibited on the premises’. A large room was also considered to prevent ‘perpendicular drinking’ around the bar and to slow down the consumption of drink. The ideal interior was one accessed through a wide entrance door leading towards a large feature fireplace. Wall panelling was used in wood, cork, lino rubber or vitrolite. At the Vale, Daybrook, Nottingham, T Cecil Howitt made extensive use of panelling. The Smoke Room and Lounge Hall has fairly traditional light oak panelling, brought up to date by the use of inlaid bands of silver gilt. This theme is followed through to the Lounge, which was panelled with silver-gilt fibre board.

With the coming of the second world war, new pub development came to a sudden end. Although some planned pre-war buildings were adapted and carried over after the wartime building freeze, the Improved Public House had lost its popularity. The requirements of brewers, customers and magistrates had changed significantly. Social changes of the late 20th century made many aims of the Improved Public House obsolete and led to their decline. The Victorian pub again regained its position.

A blank canvas

To the modern pub designer the pub is seen as a shell to be gutted, a blank canvas for maximising profitable space. Maximising the drinking, and more recently eating, area of a pub is a priority. With the total gutting and loss of internal partitions comes the introduction of repetitive brand standardisation, with the loss of individual character. The final irony is that so much of this heritage character being created is still Victoriana for pub interiors regardless of age. In an interior which conceptually tried so hard to rid itself of the excesses of the Victorian gin palaces, it is an anathema. Inter-war interiors were disguised under fitted carpets, carpeted bar fronts, obtrusive curtaining and period bric-abrac. Internal refurbishment presents a greater threat to the inter-war pub than to its chronological predecessors whose historic value has been more widely recognised.

Even those pubs recognised as significant and listed are still threatened, initially by the financial pressure affecting the survival of all pubs and, it appears, by the failure of those involved in the planning process to properly understand the building, its history and its significance. Conversion to other uses is common even among the listed Improved Public Houses. The list description for the Five Ways, Nottingham, by AE Eberlin (1936, Grade II) states that ‘The substantially complete survival of the plan and fittings in “improved” inter-war public houses is an increasingly rare occurrence’. But the Five Ways closed as a pub in 2014 and is now used as a community centre and mosque, and little of this once-rare interior seems to survive. Not far away the Oxclose, Arnold, Nottingham, by T Cecil Howitt (1939, Grade II) is in use as a Chinese restaurant. More examples include the Dr Johnson, Barkingside, London, by H Reginald Ross (1937, Grade II), which has been converted to a Co-op, and the Dog and Partridge, Hall Green, Birmingham, by JP Osborn (1929, Grade II), which has been converted to a church.

If the public house is generally a neglected building type, the Improved Public House has fared much worse. Its large spaces and lack of snug homeliness have made it unpopular and ripe for a new Victorianisation. For many years it was little researched and little appreciated, and then it was too late. The rate of major refurbishment and total loss was such that much of the historic fabric was destroyed before any assessment could be made. Around 6,000 public houses were thought to have been built, rebuilt or extensively remodelled in the inter-war years, but very many have been demolished or significantly altered. In England today fewer than 100 are listed.

The addition of 19 new inter-war pubs to the list in 2015 came too late for many, including the 1921 Carlton Tavern, Kilburn, which was demolished before it could be listed. Over the past four decades especially, the pub’s survival has been constantly threatened by wholesale radical refurbishment, or by closure, conversion or demolition. Since its introduction in a blaze of glory in the 1920s and 1930s, the Improved Public House has been subsequently subjected to waves of careless neglect, substantial damage and complete destruction.

This article originally appeared in Context 165, published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in August 2020. It was written by Fiona Newton, operations director of the IHBC.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Billingsgate Market.

- Cambridge Market.

- Conservation.

- Heritage.

- IHBC articles.

- Incredible Edible Todmorden.

- Inntrepeneur Pub Company Ltd v. East Crown Ltd.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Is Wandsworth the most pub friendly council.

- John Cathles Hill.

- Listing of Sainsbury's supermarket in Camden Town.

- Significance and heritage protection at Cambridge Market.

- The changing face of the English pub.

- The decline and revival of food markets.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

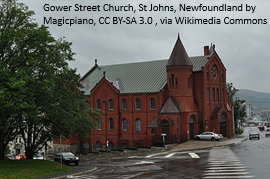

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?