The Hong Kong shophouse

Contents |

Introduction

Some 110 years of development of the Hong Kong shophouse, from the 1840s to the 1950s, has left a legacy of distinctive buildings that continue to resonate with Hongkongers.

[Taipingshan and the firstgeneration shophouses in the 1870s (Photo: copyrightfree image courtesy of the National Archives, UK)]

The Hong Kong shophouse, known locally as tong lau (literally Chinese building), is a variation of the generic urban architectural type found in predominantly Chinese cities in southern China and south-east Asia. As its name implies, it usually combines the functions of shop (on the ground floor) and house (on the upper floors).

Until the 1950s, shophouses were the main form of housing for the vast majority of the Chinese in British Hong Kong. For a variety reasons, including ethnic restrictions, available housing was disproportionate to the number of Chinese immigrants. As a result, shophouses became severely overcrowded and were referred to as tenements by the British.

The problem was compounded with the establishment of Communist China in 1949. Unprecedented numbers of immigrants arrived, worsening the tenement situation. Relief came with the launch of a mass public housing programme in the mid-1950s, followed by a more substantial 10-year public housing programme introduced by Governor Sir Murray MacLehose in 1972.

From the mid-1980s, with a property boom spurred by the successful conclusion of the Sino-British Joint Declaration that determined the fate of Hong Kong at the end of its colonial rule in 1997, shophouses in Hong Kong were demolished en masse to make way for larger-scaled and higher-valued development.

In the 19th century, as foreign powers aggressively pried open China for trade and other economic gains through treaty ports, shophouses provided a politically stable and economically vibrant environment to thousands of Chinese desperately seeking a way out of poverty and lack of opportunity. Those from Guangdong province were especially drawn to the nearby colony of Hong Kong, and the British authorities welcomed the immigrants as they provided needed services and skills as well as business resources.

By 1843, just two years after the British hoisted the Union Jack on Hong Kong Island, emigrant Chinese began to settle in an area to the west of the business district of Central and the military cantonment of Admiralty. By the early 1880s this Chinese settlement area would become known as the Taipingshan district. It occupied an area of about three square kilometres and housed an estimated population of 210,000 people (Pryor 1975: 65). Its rudimentary shophouses lacked adequate daylight, ventilation and drainage. To compound matters, there was no effective separation between the kitchen and the toilet. Given these conditions, it is not surprising that, in May 1894, an overpopulated Taipingshan became the epicentre of an outbreak of bubonic plague. The plague cost the lives of thousands, and triggered a fundamental shift in the design of Hong Kong’s shophouses.

[No 120 Wellington Street, an example of Hong Kong’s firstgeneration shophouses (Photo: Ho-Yin Lee)]

The need for a shift was understood as early as 1881, if not before. It was in this year that Osbert Chadwick (1844–1913), a former Royal Engineer, was commissioned by the Colonial Office to investigate sanitary conditions in Hong Kong, especially those in Taipingshan. The investigation was in response to complaints from the commander of the local military garrison, who blamed the poor sanitation in Taipingshan for the high mortality rate among soldiers. The result of the investigation was published in the 1882 Mr Chadwick’s Report on the Sanitation Condition of Hong Kong (more commonly known as Chadwick’s Report). The section entitled ‘Chinese Houses’ would become the basis for Hong Kong’s first comprehensive set of building regulations (Public Health and Buildings Ordinance 1903) more than 20 years later.

Unfortunately, the recommendations made in the 1882 report were resisted by both the European and Chinese business communities due to the extra cost involved in building shophouses with better living spaces and improved sanitation facilities. Chadwick’s recommendations would not receive appropriate attention until 1894, with the deadly bubonic plague outbreak in Taipingshan. Even then, matters dragged on. In a particularly cruel twist of fate, Chadwick was commissioned to write a second report, Preliminary Report on the Sanitary Condition of Hong Kong. The report, which reiterated much of the 1882 report, was presented to the Legislative Council in April 1902, eight years after the deadly outbreak.

Resistance to Chadwick’s earlier 1882 report is clear, as the opinion of another British specialist, WJ Simpson, professor of hygiene at King’s College and lecturer in tropical hygiene at the London School of Tropical Medicine, was sought after the 1894 outbreak. Simpson prepared a memorandum to the Sanitary Board, dated March 1902, which highlighted the unsanitary conditions found in Taipingshan shophouses, reinforcing what Chadwick had said years before. With the combined recommendations made by Chadwick and Simpson, the aforementioned Public Health and Buildings Ordinance of 1903 was drafted. It was this ordinance that established standards for the design of shophouses. The new regulations followed Chadwick’s 1882 recommendations closely, stipulating the following:

- Provision of open space and a scavenging lane of at least six feet wide (about 1.8m) behind buildings (Clause 179). This regulation ensured that the backs of shophouses could have windows for light and air, and that the collection of rubbish, night soil and pig swill could be done from the back.

- Building height limited to the width of the fronting street, and not more than four storeys, or higher than 76ft (about 23m) (Clause 188). This regulation controlled the height of shophouses so that fronting streets could receive adequate sunlight and fresh air.

- Building depth limited to 40ft (about 12m) (Clause 151). This regulation helped to curb the number of subdivided tenement cubicles in long narrow shophouses.

In Hong Kong the traditional approach of categorising shophouses based on style is problematic, as early shophouses are generally devoid of stylistic markers and later shophouses can exhibit an exotic stylistic cocktail. However, having documented a representative number of extant shophouses, the authors have been able to group shophouses by construction periods, noting, in particular, materials and techniques. They have chosen to refer to the different periods as different generations, each distinctive, but genetically related.

First-generation shophouses, 1840s–1890s

Not surprisingly, the first generation of Hong Kong shophouses replicated traditional southern Chinese shophouses, which were constructed of Chinese grey brick (walls), timber (beams and floorboards) and clay tiles (roofing). The absence of ornamentation reflected clearly the economic state and preferences of the local Chinese community. The only known extant example of the first generation shophouse is No 120 Wellington Street, completed in 1884.

Second-generation shophouses, 1900s–1920s

The second generation of Hong Kong shophouses reflected the requirements of the first set of building regulations (introduced in 1903), and the availability of new building materials and advanced construction technology. The local production of Portland cement, which began in 1890, encouraged the use of reinforced-concrete construction. However, as an emerging technology, it was used sparingly, and mainly for the construction of cantilevered balconies. A notable example is the Blue House at Nos 72–74A Stone Nullah Lane, completed in 1922. By the late 1920s the maturing of the technology saw the application of reinforced concrete for floor slabs as well.

[The popularly named Blue House at No 72–74a Stone Nullah Lane, an example of Hong Kong’s second-generation shophouses (All photos: Ho-Yin Lee)]

Third-generation shophouses, 1930s–1940s

By the 1930s, reinforced concrete was the preferred means of construction, not only for balconies but also for floors, walls and roofs. Stylistically, shophouses built in the early part of the 1930s exhibit a combination of classical and art-deco elements, reflecting the international transition from a more traditional language to one more modern. One example is Lui Seng Chun at No 119 Lai Chi Kok Road, completed in 1931. Shophouses built towards the end of the 1930s tend to be more art deco in aesthetic character.

[No 119 Lai Chi Kok Road, a third-generation shophouse]

Fourth-generation shophouses, 1950s

Property development in Hong Kong came to a standstill during the war years (1941 to 1945). However, as the economy recovered throughout the 1950s, the fourth generation of Hong Kong shophouses reflected the fuller potential of reinforced-concrete construction. Shophouses were typically six storeys high (two storeys more than the pre-war limit) and of austere appearance due to the state of the economy and the influence of modernism. Examples of this generation can be found throughout Hong Kong, such as the shophouse at No 31 Wing Fung Street, completed in 1957.

[No 31 Wing Fung Street, a fourth-generation shophouse]

The end of an era

The development of the Hong Kong shophouse lasted some 110 years, from the 1840s to the 1950s. The demise of the shophouse type was directly related to post-war population growth, and its associated housing and commercial needs. Simply put, the traditional shophouse, in all its guises, became an obsolete form of real-estate development. By the early 1960s it was completely superseded by mixed-use composite buildings and ultimately, high-rise buildings. Left behind is a legacy of distinctive buildings that continue to resonate with generations of Hongkongers.

References

- Chadwick, Osbert (1882) Mr Chadwick’s Report on the Sanitary Condition of Hong Kong, Colonial Office, London

- Chadwick, Osbert (1902) Preliminary Report on the Sanitary Condition of Hong Kong, Public Works Office, Hong Kong,

- Emrys Evans, Dafydd (1970) ‘Chinatown in Hong Kong: the beginnings of Taipingshan’, Journal of the Hong Kong Branch Royal Asiatic Society, Vol 10

- Lee, Ho-Yin (2003) ‘The Singapore Shophouse: an Anglo-Chinese urban vernacular’, in Asia’s Old Dwellings: tradition, resilience, and change, edited by Ronald G Knapp (115– 134), Oxford University Press, New York

- Lee, Ho-Yin and DiStefano, Lynne (2015) Tong Lau: A Hong Kong Shophouse Typology, a resource paper for the Antiquities and Monuments Office,

- Architectural Services Department, Buildings Department, Commissioner for Heritage’s Office and Urban Renewal Authority

- Pryor, Edward George (1975) ‘The Great Plague of Hong Kong’, Journal of the Hong Kong Branch Royal Asiatic Society, Vol 15

This article originally appeared in Context 145, published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in July 2016. It was written by Ho-Yin Lee and Lynne D Distefano, associate professor and the head of division of architectural conservation programmes at the University of Hong Kong. Lynne DiStefano is adjunct professor and academic advisor in the same division.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Architectural styles.

- Beijing National Stadium.

- Britain-China trade and investment.

- China-UK research deal for sustainable cities.

- Chinese renaissance architecture in China and Hong Kong.

- Conservation.

- Conservation area.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation

- Listed building.

- Liveable Yangon: for whom?

- Restoring Singapore shophouses.

- Tallest buildings in the world.

- The changing form of building worldwide 1984.

- The Chinese construction industry.

- Traditional dwellings of Dajun.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

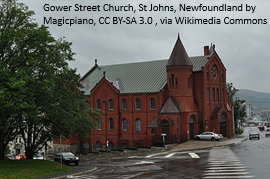

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?