Chinese renaissance architecture in China and Hong Kong

This article originally appeared in Context 145, published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in July 2016. It was written by Ho-Yin Lee and Lynne D Distefano.

In the 1920s western-trained Chinese architects offered an architectural identity for the new China, but after the 1949 revolution the style had to find its place beyond the mainland.

[The Shanghai Municipal Government Building, designed by Doon Dayu, completed in 1933 (Photo from Doon’s 1936 article)]

Chinese renaissance architecture is an aesthetic created by a group of primarily American-trained, first-generation Chinese architects who formed a movement for the rejuvenation of Chinese architecture in modern China. The architectural movement is set within the framework of renewed national pride and consciousness in a newly established Republican China (officially, the Republic of China, which lasted from 1911 to 1949) after over half a century of humiliation by western imperialism.

The movement was initiated in the 1920s and vigorously developed throughout the 1930s before it was dampened by the Japanese invasion and occupation of China (1937–1945). Doon Dayu (1899–1975), a 1927 graduate of Columbia University, wrote in a 1936 article in the English-language T’ien Hsia Monthly (published from 1935 to 1941): ‘A group of young students went to America and Europe to study the fundamentals of architecture. They came back to China filled with ambition to create something new and worthwhile. They initiated a great movement, a movement to bring back a dead architecture to life: in other words, to do away with poor imitations of western architecture and to make Chinese architecture truly national’ (Doon, 1936).

The story of this architectural development starts in the late 1920s, when the first architects from the Chinese Republic returned home after graduating from the architectural schools of elite American universities such as Cornell, Illinois, Michigan, MIT and Pennsylvania. Motivated by intense nationalism, the young architects aimed to modernise a Chinese society that was mired in its imperial past. The means to do so was through western rationalism and scientific methods embedded in the study of architecture at western universities. However, these vanguard students would soon discover the contradiction of being modern and Chinese at the same time. Tony Atkin (2011) writes: ‘Although their coursework and studios involved the rigorous study of western accomplishments in architecture, most of them struggled with the idea of how to be modern (usually equated with western ideas) and still be Chinese.’

The famous Chinese reformist and educator Liang Chi-chao (1874–1929) believed that the contradiction could be reconciled ‘through a deep understanding of ancient Chinese history and Confucian philosophy, and their reintegration into modern life, much in the way that the Italian renaissance was built on the restoration of ancient Greek and Roman culture, art, and humanism.’ Liang happened to be the father of one of these first-generation American-trained Chinese architects – Liang Ssu-cheng (1901–1972), a 1928 graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and arguably the most renowned member of China’s first-generation architects and architectural educators. As a leading academic, the younger Liang contributed significantly to the movement through his rediscovery of classical Chinese architectural rules, especially those relating to proportions and aesthetics, and through his promotion of the use of these rules with modern (western) architectural construction.

This deep understanding of classical Chinese architecture, combined with an understanding of modern construction technology, especially reinforced concrete, allowed the first-generation of western-trained architects to create a distinctive Chinese aesthetic that would come to be known as Chinese renaissance architecture.

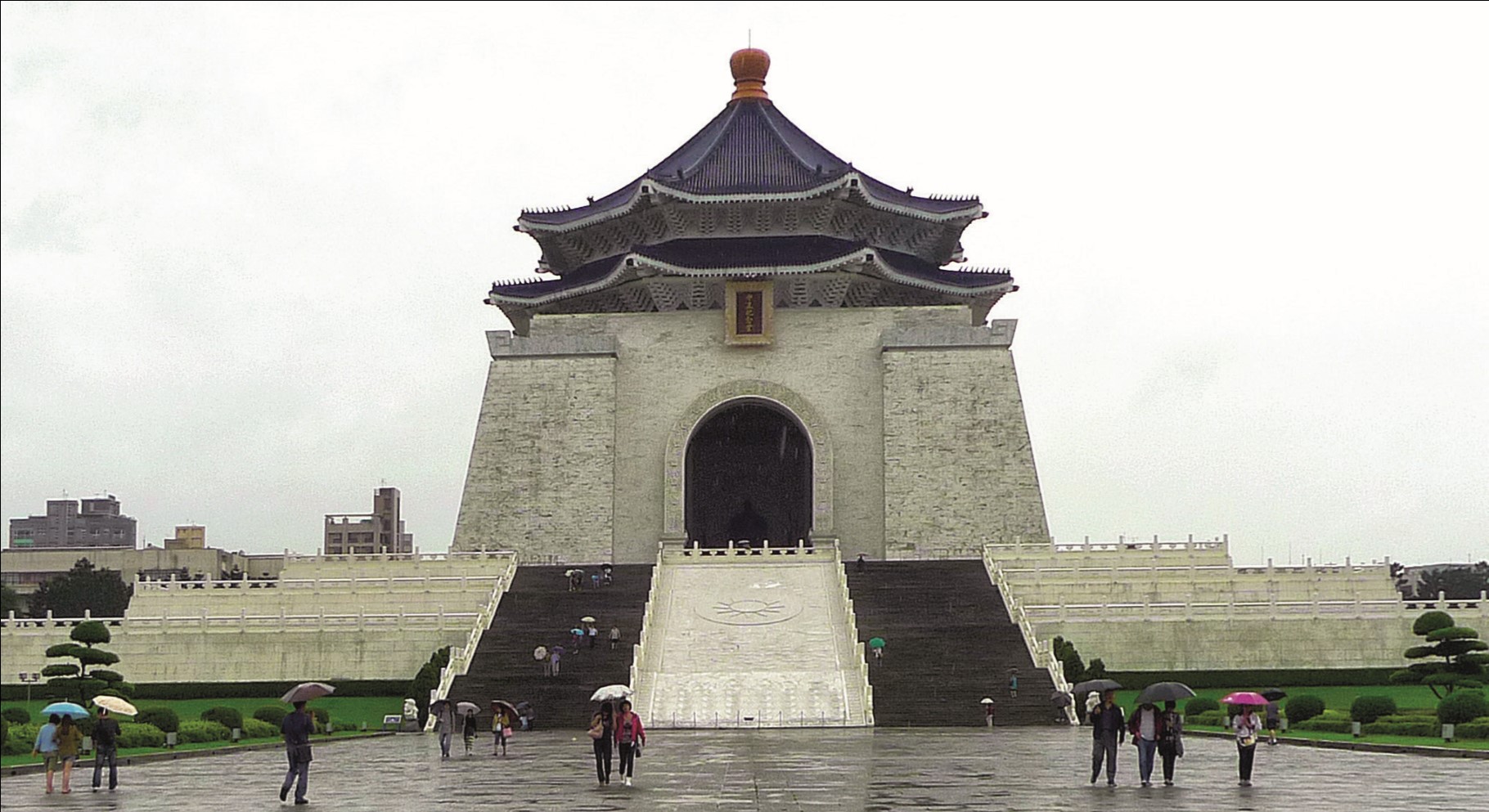

[The National Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall (1980) in Taipei (Photo: Ho-Yin Lee)]

[The National Theatre (1987) in Taipei (Photo: Ho-Yin Lee)]

Some of the more striking examples can be found in the former capital city of Nanjing, such as the Officer’s Club (1931) and the Ministry of Railways Building (1933), and in the pre-war cosmopolitan city of Shanghai, such as the Municipal Government Building (1933), Municipal Stadium (1934), Municipal Museum (1935) and Municipal Library (1936). Almost all of these examples were converted to other uses after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

Since Chinese renaissance architecture was an integral part of the national rejuvenation political ideology of the Kuomintang (the ruling nationalist party of Republican China), it is not surprising that the movement was purged by the communist regime after it assumed power in 1949. However, the distinctive architecture continued to be built on the island of Taiwan, where the defeated Kuomintang regime had retreated and remained in power.

A series of buildings important to the Kuomintang regime in Taiwan was built in the capital city of Taipei, using the language of Chinese renaissance architecture: the National Museum of History (1960), National Palace Museum (1965), Grand Hotel (1973), National Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall (1980), National Theatre (1987) and National Concert Hall (1987).

Architectural design in the British colony of Hong Kong was influenced by Chinese renaissance architecture during the 1930s, at the height of the movement. The aesthetic character of Chinese renaissance architecture, in particular, appealed to Christian institutions. Distinguished examples (all of which are graded historic buildings) include the Tao Fung Shan Christian Centre (1930), Holy Spirit Seminary (1931), Chinese Methodist Church (1932, demolished in 1994), Holy Trinity Church (1937, now Holy Trinity Cathedral) and St Mary’s Church (1937).

[St Mary’s Church (1937) in Hong Kong, a Grade 1 historic building (Photo: Ho-Yin Lee)]

[The Chinese Methodist Church (1932) in Hong Kong, demolished in 1994 (Photo: Ho-Yin Lee)]

The nationalistic ideology of Chinese renaissance architecture appealed to the elite class of the local Chinese population, who saw the style as a means of asserting their ethnic identity in the British colony. The result is a small number of significant examples, including Ho Tung Gardens (1927, demolished in 2013), Haw Par Mansion (1935, a Grade 1 historic building), former residence of General Ting-Kai Tral (1936, now the Morrison Building, a declared monument) and King Yin Lei (1937, a declared monument).

However, Chinese renaissance architecture had a relatively low profile in Hong Kong. First, for public and institutional buildings there was a strong preference among government agencies and institutions for western styles. Second, for residential buildings the palatial aspect of Chinese renaissance architecture had limited appeal to the large majority of local Chinese.

After the second world war there was even less interest in Chinese renaissance architecture in a rapidly modernising Hong Kong. At the same time, some of the main proponents of the movement from mainland China moved to the British colony. In adjusting to the new political reality, they too abandoned Chinese renaissance architecture and adopted the language of modernism.

[The gateway of the Tang Chi Ngong School of Chinese at the University of Hong Kong (1931) (Photo: Lsoadrimak at Wikimedia Commons, used under attribute-share licensing)]

[The mansion King Yin Lei (1937) in Hong Kong, a declared monument (Photo: Ho-Yin Lee)]

Chinese renaissance architecture reflected the quest of China’s first-generation, western-trained architects for a fitting architectural identity for the new China. As Dayu Doon (1936) wrote: ‘The architect must express and country.’ Chinese renaissance architecture reflects himself in the language of his own times. Only thus will the zeitgeist of Republican China, but its nationalistic the architect be able to produce buildings that will truly ideology became its Achilles heel as mainland China reflect the hopes, the needs, and the aspirations of his age moved to a new political reality after 1949.

References and further reading:

- Atkin, Tony (2011) ‘Chinese architecture students at the University of Pennsylvania in the 1920s: tradition, exchange, and the search for modernity’ in Cody, Jeffery, et al, (eds) Chinese Architecture and the Beaux-

- Arts, University of Hawaii

- Press/Hong Kong University

- Press, Honolulu/Hong Kong

- Doon, Dayu (1936)

- ‘Architectural Chronicle’, T’ien Hsia Monthly, Vol 3, No 4, republished in the online China Heritage Quarterly, June 2010, China Heritage Project, Australian National University

- Fu, Chao-Ching (2011)

- ‘Beaux-Arts Practice and

- Education by Chinese

- Architects in Taiwan’ in Cody, Jeffery, et al, (eds) op cit

- Lee, Ho-Yin, DiStefano,

- Lynne and Tse, Curry

- (2011) ‘Architectural

- Appraisal of Ho Tung Gardens’, consultancy report commissioned by the HKSAR Antiquities and Monuments Office in preparation for the declaration of Ho Tung Gardens as a monument

- Su, Gin-djih (1964) Chinese Architecture: past and contemporary, Sin Poh Amalgamated (HK), Hong Kong Ltd

- Wang, Hao-Yu (2008)

- Mainland architects in Hong Kong after 1949: a parallel history of modern architecture in China, PhD thesis, University of Hong Kong.

Ho-Yin Lee is associate professor and the head of division of architectural conservation programmes at the University of Hong Kong. Lynne DiStefano is adjunct professor and academic advisor in the same division.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- 10 great buildings.

- Architectural styles.

- Beijing National Stadium.

- Britain-China trade and investment.

- Build operate transfer BOT.

- Chinese brutalism.

- China-UK research deal for sustainable cities.

- Chinese Wallpaper in Britain and Ireland.

- Conservation.

- Conservation area.

- Duplitecture.

- Feng shui.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Listed building.

- Restoring Singapore shophouses.

- Tallest buildings in the world.

- The changing form of building worldwide 1984.

- The Chinese construction industry.

- The Hong Kong shophouse.

- Traditional dwellings of Dajun.

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.