Definition of collateral warranty

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Construction projects, by their very nature and also by their method of procurement, create complex legal relationships between the many parties involved. The finished product has, or should have, a life expectancy calculated not in years but in tens of years giving rise to a class of future owners who had no involvement in, or control over, the original contract works but who may have substantial liabilities if things go wrong.

It is because of these characteristics that tort was a useful remedy permitting a much wider forensic examination of liability and a greater potential for remedy and indeed disputes. Tort also permitted a more flexible apportionment of blame amongst the parties involved in the actual construction process. However, the use of tort as a remedy in construction cases has been substantially eroded, and in its place there is now widespread use of a contractual remedy in the form of collateral warranties.

In contract, the role of the court is restrictive, unlike tort, where its role is creative. In contract, subject to statutory exceptions, the basic role of the court is to police a set of rules to ensure that all the component parts of a binding contract have been satisfied. The nature and substance of the bargain between the parties is a matter of private agreement provided of course that the bargain is not illegal or contrary to public policy. In tort the duty and standard of care is created by the courts and is not a matter of private bargain.

A basic rule of contract is the doctrine of privity of contract. This doctrine states, as a general rule, that only a party to a contract can take the benefits of that contract or is subject to its burdens or obligations. For example, if A promises to B to pay a sum of money to C, as a general rule, C cannot enforce that obligation against A. However, this rule has been fundamentally changed by the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999.

A collateral warranty has been, and probably remains, notwithstanding the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act, one of the ways of overcoming the restriction on remedies created by the doctrine of privity. In law, the term collateral warranty has several meanings.

It may mean a warranty or representation which is collateral to the main transaction. For example, in the case of De Lassalle v. Guildford, L had agreed the terms of a lease with G. However, L refused to complete the transaction unless and until he had been given an assurance by G that the drains of the property were in good order. G gave an appropriate verbal assurance and L completed the lease document. After going into possession of the property, L found that the drains were defective. He was not able to bring an action under the terms of the lease however he claimed damages against G on the basis of a collateral warranty created by G's verbal assurances. L's action succeeded.

A collateral warranty which is collateral to the main transaction will give an additional cause of action to one of the parties to that transaction but does not introduce a third party.

However, the term collateral warranty has a further meaning, namely a binding contract entered into between B and C which is collateral to a contract already in existence between A and B, whereby B promises to C that he will perform his obligations to A. If B is in breach of those obligations to A then C will have a right of action against B. This collateral warranty or collateral contract may be imputed, that is to say arising implied as a matter of fact from the circumstances of a particular case, or by the parties entering into a specific, usually written contract.

A further species of collateral warranty is a unilateral undertaking entered into by one party in favour of another, the document being under seal.

In Shanklin Pier Ltd v. Detel Products, S who were owners of a pier entered into a contract with G.M. Carter (Erectors) Ltd for the repair and repainting of the pier, the repainting to be carried out with two coats of bitumastic or bituminous paint. Under the terms of their contract with Carter, S reserved the right to vary the specification. D were paint manufacturers who produced a product known as DMU which they represented to S as being suitable for the repainting of the pier in that its surface was impervious to dampness and could prevent corrosion and creeping of rust with a life of 7-10 years.

In consideration of this representation S specified to Carter that Carter should use D's paint. The paint proved to be a failure and S sued, not Carter as main contractor, but D as supplier of the paint. D argued that they had not given any such representation or warranty and even if they had it did not give rise to a cause of action because they were not parties to the contract for repainting the pier.

The court rejected this argument and held that on the facts there was a warranty and that the consideration for the warranty was that S should cause C to enter into a contract with D for the supply of their paint for repainting the pier. The representations given by D to S were contractually binding in the form of a collateral contract which arose by imputation. In the Shanklin case, D was aware that their product was to have a specific use by a third party.

This was not the situation in Wells (Merstham) Ltd v. Buckland Sand and Silica Co Ltd. B were sand merchants and they warranted to W who were chrysanthemum growers that their sand conformed to a certain analysis that would be suitable for the propagation of chrysanthemum cuttings.

W ordered a load of sand direct from B and a further two loads via a third party who were builders merchants and not horticultural suppliers, that is to say they supplied sand for various purposes. The third party purchased two loads of sand from B for onward sale and delivery to W and gave no indication to B that the sand was required for W or for horticultural purposes. The sand did not conform with the analysis and as a result W suffered a loss in the propagation of their young chrysanthemums.

The court held that B was liable on the basis of a collateral contract and that it was irrelevant that the purchase of the sand had been made through a third party; as between a potential seller and a potential buyer only two ingredients were required to bring about a collateral contract:

(1) a promise or assertion by the seller as to the nature, quality or quantity of the goods which the buyer might regard as being made with a contractual intention; and

(2) the acquisition by the buyer of the goods in reliance on that promise or assertion.

In contrast to the decisions in Shanklin and Wells, the court in Drury v. Victor Buckland Limited rejected the plaintiffs claims against the defendant. In this case D was approached by an agent of V in order to persuade D to purchase an ice cream maker. D had doubts as to whether she could afford the equipment; however she was persuaded to pay a 10 guinea deposit to V and to discharge the balance of the purchase price by way of installments to a finance company.

The full terms of the transaction were set out on an invoice sent to D by V; however, the deal was put through by V selling the machine to a finance company who in turn entered into a hire purchase agreement with D. The machine proved unsatisfactory and D brought proceedings against V on the basis that V was in breach of the implied warranties or conditions as to quality imposed by the Sale of Goods Act 1893. The court held that there was no contractual relationship between D and V.

From the case report, it does not appear that D tried to argue that there was a collateral contract. There was evidence before the court that 'in the course of one or other of the interviews in answer to her question "suppose it goes wrong?" he (the defendant's agent) said that if it did she was to ring them up and that she had no need to worry about it as they would service it for 18 months free'. At the very least it would appear arguable that those words could have constituted a collateral warranty giving rise to an obligation between D and V.

A helpful description of the nature of a collateral contract was given by Lord Moulton in the case of Heilbut Symons & Co v. Bucklekm when he stated:

‘...it is evident, both on principle and on authority, that there may be a contract the consideration for which is the making of some other contract. If you will make such and such a contract I will give you £100 is in every sense of the word a complete legal contract. It is collateral to the main contract but each has an independent existence and they do not differ in respect of their possessing to the full the character and status of a contract.’

Lord Moulton places an emphasis on the word ‘contract’. In the cases of Shanklin and Wells the courts found that collateral contracts arose by implication from the facts of each case. In the construction industry collateral contracts will invariably arise by the acts of the parties entering into a specific agreement. Regardless of whether the contract arises by implication or by specific agreement, a basic understanding of the rules as to the formation and construction of a contract is an essential prerequisite to understanding the problems arising from collateral warranties.

In the case of Inntrepeneur Pub Company Ltd v. East Crown Ltd the court held that an entire agreement clause did not merely render evidence of the giving of the collateral warranty inadmissible but it also deprived what would otherwise have been a valid collateral warranty of its legal effect. The entire agreement clause was worded as follows:

'Any variation of this agreement which are [sic] agreed in correspondence between the parties shall be incorporated in this agreement where that correspondence makes express reference to this clause and the parties acknowledge that this agreement (with the incorporation of any such variations) constitutes the entire agreement between the parties.’

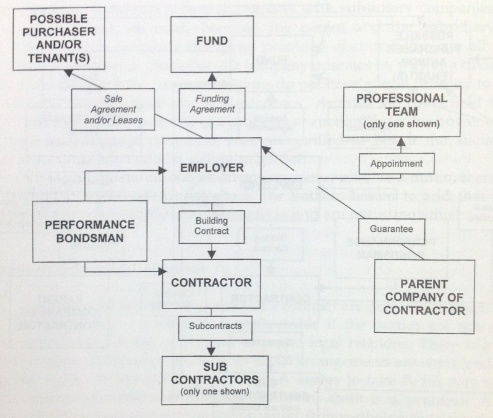

The provision of a contractual network of collateral warranties for a typical building project creates a network of considerable complexity. Figure 1.1 sets out in diagrammatic form the contractual arrangements arising from an unmodified JCT 98 Standard Form of Building Contract (without contractor's design).

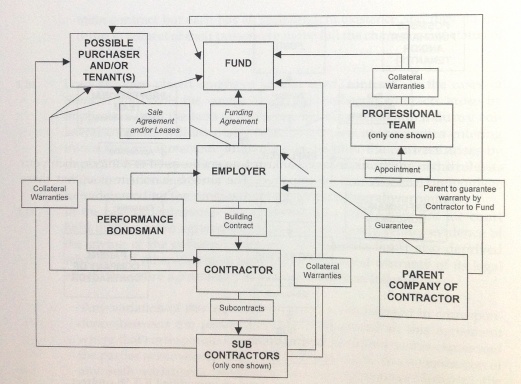

By comparison, Fig. 1.2 sets out a typical arrangement after the parties have entered into the collateral warranties that are now commonly sought in respect of a building development.

Figure 1.1: Unmodified JCT 98 Standard Form of Building Contract (without contractor's design)

Fig. 1.2: Typical arrangement in respect of a building development.

[edit] Parkwood Leisure Limited v Laing

In the case of Parkwood Leisure Limited v Laing O’Rourke Wales and West Limited in 2013, the judge found that Parkwood’s collateral warranty was a construction contract as the definitions were widely construed and The Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act applies to all contracts related to the carrying out of construction operations.

The court’s decision is an unexpected one for practitioners who assumed the Act did not apply to warranties.

Collateral warranties will now be subject to greater scrutiny in the light of this case. We may now see a resistance among contractors and consultants to grant warranties and a desire to perhaps restrict the number and scope of warranties so that their application is limited to be retrospective only. That inevitably means further complications for the negotiation and drafting of warranties resulting in protracted and costly negotiations.

The decision also raises speculation as to the application of the Act’s Scheme for Construction Contracts and payment provisions to warranties considered to be construction contracts.

The upshot of this could now see the rise of third party rights as circumventing the issues arising from this case. Could this spell the end of the widespread use of warranties which may finally be falling out of favour?

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Appointing consultants.

- Collateral.

- Collateral warranties.

- Consultant switch.

- Contracts.

- D&F Estates Limited and Others v Church Commissioners for England and others.

- Defects.

- Design and build.

- Design liability.

- Designers.

- Difference between collateral warranties and third party rights.

- Murphy v Brentwood District Council.

- Novation.

- Parkwood Leisure Limited v Laing.

- Performance bond.

- Practical considerations of collateral warranties.

- Professional indemnity insurance.

- Sub contractors.

- The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act.

[edit] External references

Featured articles and news

Independent Building Control review panel

Five members of the newly established, Grenfell Tower Inquiry recommended, panel appointed.

ECA progress on Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter

Working hard to make progress on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.

Many resources for visitors aswell as new features for members.

Using technology to empower communities

The Community data platform; capturing the DNA of a place and fostering participation, for better design.

Heat pump and wind turbine sound calculations for PDRs

MCS publish updated sound calculation standards for permitted development installations.

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.

Comments

To start a discussion about this article, click 'Add a comment' above and add your thoughts to this discussion page.