The genealogy of classicism

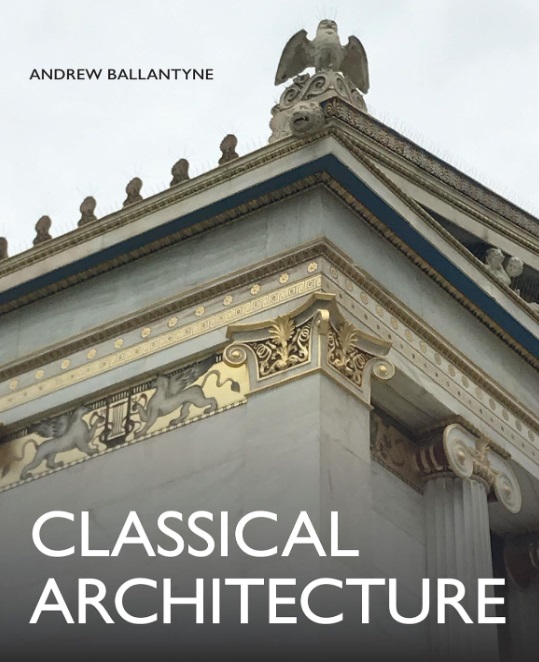

Classical Architecture, Andrew Ballantyne, Crowood Press, 2023, 160 pages, colour and black-and-white illustrations, hardback.

The late Umberto Eco demonstrated in his book Dire quasi la stessa cosa (‘Saying almost the same thing’) how meanings and connotations can get lost in translation, and that words and terms rarely cover the same ground in different languages. His observations could easily be applied to the word ‘classical’ and even more so to the term ‘classical architecture’.

On the European continent, for example, especially in predominantly Roman Catholic countries and regions and in their native languages, this term tends to be associated either with ancient Greek and Roman architecture, or with its learned reincarnations (classicism or neoclassicism), but not normally with both, and to an even lesser degree with the various manifestations of baroque architecture. The great Borromini would not be deemed classico in Italy, neither would the brothers Johann Baptist and Dominikus Zimmermann be considered klassisch in German-speaking countries.

But Andrew Ballantyne’s new book has been written for an English-speaking readership more prevalent in the protestant parts of the globe and with less exposure to the architecture of the counter-reformation. Britain and America have always had a soft spot for Palladio, and an appreciation of the seemingly unbroken line of his architectural predecessors and successors from antiquity to modernity. In Britain, certainly, ‘classical’ architecture is not dead.

Covering two-and-a-half millennia, the author and former chairman of the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain uses a holistic approach to examine the origins of classical architecture and to illustrate its evolution up to the present day. He dedicates eight chapters to ‘Ancient Greece’, ‘Ancient Rome’, ‘Byzantium’, ‘Romanesque’, ‘Renaissance’, ‘Baroque and Rococo’, ‘Neoclassicism’ and ‘Eclectic Classicism’ respectively. Starting with the classical orders (Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and Composite), he illustrates how these omnipresent features have been invented and reinvented, modified and standardised, adapted and integrated, interpreted and misinterpreted, and how the ancient DNA of Greek and Roman architecture can still be traced in modern and postmodern designs. This inclusive genealogy of classicism pays equal tribute to every period that is related, however remotely, to the architecture of antiquity.

Ballantyne’s own research interests in ethics, metaphysics and aesthetics become apparent in the weight he attaches to the fertile ground of ideas behind classical design. The focus on architectural theory is particularly rewarding in his chapter on neoclassicism, which includes sections on post-baroque classicism (Abbé Laugier), romantic fundamentalism (Rousseau) and Ledoux. The book’s final chapter, on eclectic classicism, detects the influence of Winckelmann, Viollet-le-Duc, Semper, Ruskin and Heidegger in the inexhaustible diversity of the modern age, while revisiting the work of modern and contemporary architects such as Mies van der Rohe and Chipperfield, alongside their antipodes Moore and Outram. It contains a poignant section on ‘The timeless beauty of ancient classical architecture’, in which the author exposes its universalism as an illusion.

This book serves as introduction rather than scholarly investigation. 2,500 years have been accommodated in just under 150 pages of text (including 112 illustrations) with no bibliography and no footnotes, although a useful glossary has been supplied. But just as about half of all the photographs have been taken by the author himself, so is the text a personal statement promoting what connects these different styles from different ages and therefore justifies a macro-historic synopsis. The language is delightfully accessible and to the point, and the monograph so fluently and compellingly written that one can easily absorb the whole volume in one go. Familiar and less-familiar examples are presented and illustrated as visual meat on the backbone of universal truths.

Take the beginning of chapter two (‘Ancient Rome’): ‘If I try to build by myself, I don’t get very far. My energy and my money are soon used up. For great monuments to exist there have to be concentrations of power’. That may not sound awfully academic, but as a starting point to explain Rome’s increasingly colossal architecture and impact it works rather well.

This article originally appeared as ‘On the genealogy of classicism’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 178, published in December 2023. It was written by Michael Asselmeyer, historian and architect.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Classical architecture.

- Classical orders in architecture.

- Classical Revival style.

- Conservation.

- Elements of classical columns.

- Heritage.

- Historic environment.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Italian Renaissance Revival style.

- Neoclassical architecture.

- Nineteenth century building types.

- Origins of Classical Architecture.

- Palladian architecture.

- Roman Classical orders in architecture.

IHBC NewsBlog

IHBC Context 183 Wellbeing and Heritage published

The issue explores issues at the intersection of heritage and wellbeing.

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.

National Audit Office (NAO) says Government building maintenance backlog is at least £49 billion

The public spending watchdog will need to consider the best way to manage its assets to bring property condition to a satisfactory level.