Sinkholes

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

The term 'sinkhole' is usually used to describe a surface depression, hollow or collapse feature occurring above a cavity in the ground formed by the solution of rock by the passage of water over time. There are six main types of sinkhole as classified by Waltham et al. (2005):

- Dissolution sinkhole.

- Collapse sinkhole.

- Dropout sinkhole.

- Buried sinkhole.

- Caprock sinkhole.

- Suffosion sinkhole.

Sinkholes can also form above cavities that occur as a result of other processes such as the emptying of liquid lava inside a lava flow (a Thurston Tube), ice wedging in cold climates, or large-scale movement of rock leaving chasms, known as ‘guls’.

In the UK, there has been a long history of mining and water abstraction, which in some areas has left a legacy of man-made cavities. The term sinkhole in the UK is often extended to cover the collapse of ground into such man-made features.

Suffosion and dropout sinkholes form entirely within the soil profile above the cavity with infiltrating water washing soil down into open discontinuities in the rockhead. Dissolution, collapse and caprock sinkholes are all dependent on solution and rock mechanics processes that generally occur over geological timescales related to the solubility and other properties of the country rockmass.

[edit] What causes a sinkhole?

The collapse of ground above cavities and the formation of sinkholes is almost always the result of concentrated flow of water. This might arise as a result of rainfall runoff, the construction of a soakaway, or as a result of fractured water or waste pipes or changes in natural drainage such as drawing down of the water table for major civil or mining works. Tony Waltham, went so far as to title his recent Geological Society Glossop Medal presentation, ‘Control the Drainage: The Gospel According to Sinkholes’.

On rare occasions, cavities have collapsed as a result of the failure of man-made caps, with disastrous consequences. In such cases, it has been found that the cap was simply made by placing railway sleepers over a narrow shaft entrance, and these have rotted with time, or masonry which has been buried, forgotten and not maintained.

[edit] What can civil engineers do to prevent/avoid sinkholes?

Sinkholes most commonly occur within naturally occurring karst landscape that is characterised by the formation of underground drainage and cavities from the dissolution of soluble rocks such as limestone or gypsum. Civil engineers are best served by seeking advice from geological engineering colleagues familiar with karst geohazards. Clues to the presence of sinkholes may also be found in historical records of mining and old maps.

The first step in high-risk areas is normally to consult the national database of natural and man-made cavities to establish whether known features exist close to a particular site. The general level of the hazard posed by natural features can be established using published methodologies, applying topographic and geological data. Sinkholes and Subsidence: Karst and Cavernous Rocks in Engineering and Construction, by Waltham, Bell and Culshaw, 2005, is an important resource.

In areas of higher risk it is usual to ensure that utilities can tolerate distortion without rupture and to avoid building soakaways or other features that could lead to concentrated water infiltration. Changes in the ground surface, such as depressions, circular cracks or ponding water should be reported to local authorities. In very high risk areas, special ground investigation techniques can be used to refine risk assessments, and if necessary cavities can be located and filled to prevent future collapse.

Boring tunnels into unknown features or cavities poses a significant risk to both the construction teams and to property overhead. Tunnelling into water filled cavities or where water bodies can flow catastrophically into an excavation are particularly hazardous. Tunnelling works in high-risk areas or where abandoned wells or mine shafts might be expected require particular attention during investigation phases, with techniques selected according to the conditions at any given site.

Probabilistic models for predicting sinkhole development have been proposed to inform the management of the risk from this geohazard to major infrastructure projects. Caution is recommended in the application and reliance on these methods and attention given to the importance of experience and fully understanding the geological and civil engineering factors that have caused the formation of the sinkholes and related features.

[edit] What can civil engineers do to repair sinkholes?

Generally, when a triggering action that has caused the development of a sinkhole (such as flow of water) is removed, the immediate risk to the surrounding area is substantially reduced. It is normal practice to fill smaller holes (those that commonly occur in the UK are typically less than 1000 m3 in volume) using weak concrete pumped into the hole from a safe distance. Depending on the circumstances, the sink hole is usually stabilised by concrete or other engineered infill.

Minor settlements occur for several months afterwards as the weight of the concrete settles in. New sinkholes are nearly always formed by inflow of water and are therefore largely avoided by attention to good civil engineering practices, particularly appropriate surface drainage and avoidance of large-scale changes to the water table.

It is essential to investigate the cause of the sinkhole if it is unknown, to understand the lateral and vertical extent of the related cavities, to check the stability of remaining cavities were necessary and to monitor changes that are ongoing. The potential complexity of ground conditions that can lead to sinkhole formation must be recognised and specialist advice is required.

This article originally appeared as What are sinkholes – and what can civil engineers do about them?, published by the Institution of Civil Engineers on 25 November 2015. It was written by Tony Bracegirdle (Geotechnical Consulting Group) and Matthew Free (Arup).

--The Institution of Civil Engineers

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Cracking and building movement.

- Defects in brickwork.

- Defects in construction.

- Ground conditions.

- Ground investigation.

- Ground heave.

- Groundwater control in urban areas.

- Grouting in civil engineering.

- Gully.

- Inflow.

- Institution of Civil Engineers.

- Pumps and dewatering equipment.

- Remedial works.

- Soil survey.

- Spalling.

- Subsidence.

- Sump pump.

- Underpinning.

- Why do buildings crack? (DG 361).

Featured articles and news

A five minute introduction.

50th Golden anniversary ECA Edmundson apprentice award

Showcasing the very best electrotechnical and engineering services for half a century.

Welsh government consults on HRBs and reg changes

Seeking feedback on a new regulatory regime and a broad range of issues.

CIOB Client Guide (2nd edition) March 2025

Free download covering statutory dutyholder roles under the Building Safety Act and much more.

AI and automation in 3D modelling and spatial design

Can almost half of design development tasks be automated?

Minister quizzed, as responsibility transfers to MHCLG and BSR publishes new building control guidance.

UK environmental regulations reform 2025

Amid wider new approaches to ensure regulators and regulation support growth.

The maintenance challenge of tenements.

BSRIA Statutory Compliance Inspection Checklist

BG80/2025 now significantly updated to include requirements related to important changes in legislation.

Shortlist for the 2025 Roofscape Design Awards

Talent and innovation showcase announcement from the trussed rafter industry.

OpenUSD possibilities: Look before you leap

Being ready for the OpenUSD solutions set to transform architecture and design.

Global Asbestos Awareness Week 2025

Highlighting the continuing threat to trades persons.

Retrofit of Buildings, a CIOB Technical Publication

Now available in Arabic and Chinese aswell as English.

The context, schemes, standards, roles and relevance of the Building Safety Act.

Retrofit 25 – What's Stopping Us?

Exhibition Opens at The Building Centre.

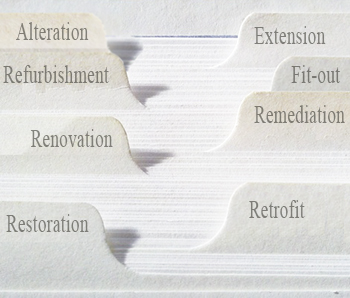

Types of work to existing buildings

A simple circular economy wiki breakdown with further links.

A threat to the creativity that makes London special.