Cross ventilation

Ventilation is necessary in buildings to remove ‘stale’ air and replace it with ‘fresh’ air:

- Helping to moderate internal temperatures.

- Reducing the accumulation of moisture, odours and other gases that can build up during occupied periods.

- Creating air movement which improves the comfort of occupants.

Very broadly, ventilation in buildings can be classified as ‘natural’ or ‘mechanical’.

- Mechanical (or ‘forced’) ventilation tends to be driven by fans.

- Natural ventilation is driven by ‘natural’ pressure differences from one part of the building to another.

Natural ventilation can be wind-driven (or wind-induced), or it can be buoyancy-driven ‘stack’ ventilation. For more information about buoyancy-driven ‘stack’ ventilation, see Stack effect.

Approved Document O: Overheating, published by HM Government in 2021, defines cross-ventilation as: ‘The ability to ventilate using openings on opposite façades of a dwelling. Having openings on façades that are not opposite is not allowing cross-ventilation, e.g. in a corner flat.’

Cross ventilation occurs where there are pressure differences between one side of a building and the other. Typically, this is a wind-driven effect in which air is drawn into the building on the high pressure windward side and is drawn out of the building on the low pressure leeward side. Wind can also drive single-sided ventilation and vertical ventilation.

Whereas cross ventilation is generally more straight-forward to provide than stack ventilation, it has the disadvantage that it tends to be least effective on hot, still days, when it is needed most. In addition, it is generally only suitable for narrow buildings.

If there are windows on both sides, then cross ventilation might be suitable for buildings where the width is up to five times the floor-to-ceiling height. Where there are only openings on one side, wind-driven ventilation might be suitable for buildings where the width is up to 2.5 times the floor to ceiling height.

Beyond this, providing sufficient fresh air creates draughts close to openings, and additional design elements such as internal courtyards are necessary, or the inclusion of elements such as atrium that combine cross ventilation and stack effects, or mechanically assisted ventilation.

Cross ventilation is most suited for buildings that are:

- Narrow.

- On exposed sites.

- Perpendicular to the prevailing wind.

- Free from internal barriers to air flow.

- Provided with a regular distribution of openings.

It is less suitable where:

- The building is too deep to ventilate from the perimeter.

- Local air quality is poor; for example, if a building is next to a busy road.

- Local noise levels mean that windows cannot be opened.

- The local urban structure is very dense and shelters the building from the wind.

- Privacy or security requirements prevent windows being opened.

- Internal partitions block air paths.

Some of these issues can be avoided or mitigated by careful siting and design of buildings. For example, louvres can be used where ventilation is required, but a window is not, and ducts or openings can be provided in internal partitions, although these will only be effective if there is sufficient open area, and there may be problems with acoustic separation.

Cross ventilation can be problematic during the winter when windows may be closed, particularly in modern buildings which tend to be highly sealed. Trickle ventilation, or crack settings on windows can be provided to ensure there is adequate background ventilation. Trickle ventilators can be self-balancing, with the size of the open area depending on the air pressure difference across it.

In straight-forward buildings, cross ventilation can often be designed by following rules of thumb for the openable area required for a given floor area, depending on the nature of the space and occupancy. The situation becomes more complicated when cross ventilation is combined with the stack effect or mechanical systems, and thermal mass and solar gain are taken into consideration. Modelling this behaviour can become extremely complicated, sometimes requiring the use of local weather data, software such as computational fluid dynamics (CFD) programs and even wind tunnel testing.

Ventilation in buildings is regulated by Part F of the building regulations and soon to be Part O.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Air infiltration testing.

- Approved Document F.

- Approved Document O.

- BREEAM Potential for natural ventilation.

- Building services.

- Computational fluid dynamics.

- Condensation.

- Humidity.

- Interstitial condensation.

- Mechanical ventilation.

- Natural ventilation.

- Passive building design.

- Dew point.

- Single-sided ventilation.

- Solar chimney.

- Stack effect.

- Thermal comfort.

- Types of ventilation.

- UV disinfection of building air to remove harmful bacteria and viruses.

- Ventilation.

Featured articles and news

A five minute introduction.

50th Golden anniversary ECA Edmundson apprentice award

Showcasing the very best electrotechnical and engineering services for half a century.

Welsh government consults on HRBs and reg changes

Seeking feedback on a new regulatory regime and a broad range of issues.

CIOB Client Guide (2nd edition) March 2025

Free download covering statutory dutyholder roles under the Building Safety Act and much more.

AI and automation in 3D modelling and spatial design

Can almost half of design development tasks be automated?

Minister quizzed, as responsibility transfers to MHCLG and BSR publishes new building control guidance.

UK environmental regulations reform 2025

Amid wider new approaches to ensure regulators and regulation support growth.

The maintenance challenge of tenements.

BSRIA Statutory Compliance Inspection Checklist

BG80/2025 now significantly updated to include requirements related to important changes in legislation.

Shortlist for the 2025 Roofscape Design Awards

Talent and innovation showcase announcement from the trussed rafter industry.

OpenUSD possibilities: Look before you leap

Being ready for the OpenUSD solutions set to transform architecture and design.

Global Asbestos Awareness Week 2025

Highlighting the continuing threat to trades persons.

Retrofit of Buildings, a CIOB Technical Publication

Now available in Arabic and Chinese aswell as English.

The context, schemes, standards, roles and relevance of the Building Safety Act.

Retrofit 25 – What's Stopping Us?

Exhibition Opens at The Building Centre.

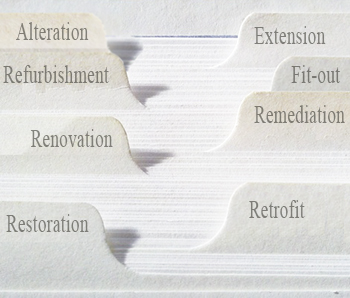

Types of work to existing buildings

A simple circular economy wiki breakdown with further links.

A threat to the creativity that makes London special.