Causation in construction contracts

In order to claim damages for breach of contract, there must be a causal link between the breach and the damage suffered by the innocent party.

In Quinn v Burch Brothers (Builders) Ltd, Q was a sub-contractor to B in respect of certain building works. There was an implied term of the sub-contract that B would supply, within a reasonable time, any plant or equipment reasonably necessary for carrying out the sub-contract works. B was in breach of that term in failing to supply a stepladder requested by Q. To prevent any delay, Q used a trestle, which he knew to be unsuitable unless it was footed by another workman. The trestle was not footed and it moved causing injury to Q.

It was held that B's breach of contract provided the occasion for Q to injure himself but was not the cause of his injury; the injury was caused by his own voluntary act in using the trestle. Accordingly B was not liable to pay damages for Q's injury, for his damage was not a natural and probable consequence of the breach of contract even if, as was in fact doubtful, it was a foreseeable consequence of that breach.

Damages for breach of contract may only be awarded for the breach itself and not for any loss caused by the manner of the breach (see Malik v Bank of Credit & Commerce International). Further, the breach of contract must be the effective or dominant cause of the loss (see Leyland Shipping v Norwich Union). But it need not be the sole cause (see Galoo v Bright Grahame Murray).

The causal link may be broken by the intervening acts of the plaintiff, as in Quinn's case, or by the intervening acts of a third party. It must be noted however that the courts are wary of laying down any general principles and many cases turn upon their own particular facts.

For example, in the case of Weld-Blundell v Stephens, S negligently and in breach of contract permitted a libellous letter written by W to fall into the hands of a third party who communicated the contents of the letter to the person who had been libelled. That person sued W, who in turn sued S. The court held that the acts of the third party broke the causal link between S's initial breach and W's damage.

A more recent example arose out of the conflict between Iran and Iraq in the 1980s in the case of Bank of Nova Scotia v Hellenic Mutual War Risks Association (Bermuda) Ltd (The Good Luck).

The claimant bank had financed the purchase by a Greek shipping group (called Good Faith) of various vessels including the Good Luck. The finance had been secured by mortgages, which required the taking out of contracts for marine insurance which extended to war risk cover. The insurance was placed with the defendants and was conditional upon the insurers' right to specify 'additional premium areas' and 'prohibited zones'. At the time, the Persian Gulf was designated both an additional premium area and, at the northern end of the Gulf, a prohibited zone. The bank took out mortgagee interest insurance with the defendant who, by letter of undertaking, agreed to advise the bank promptly if they ceased to insure.

The shipowners chartered their vessels, including the Good Luck, to Iranian charterers. The defendants were aware that the shipowners were deliberately allowing their ships to be sent to both additional premium areas and prohibited zones in the Persian Gulf and that their vessels were uninsured as a consequence. The defendants took no steps to inform the bank. In April 1982, the shipowners commenced negotiations with the bank for a rescheduling of their loan by way of an increased facility. On 6 June 1982, the Good Luck was hit by Iraqi missiles whilst proceeding up the Khor Musa Channel to Bandar Khomeini, both an additional premium area and a prohibited zone. She was badly damaged and ultimately declared a constructive total loss. The shipowners made a fraudulent claim on the defendants in respect of this loss. The bank at this time was still in the process of completing the negotiations with the shipowners for the refinancing and although the bank was aware of the loss of the Good Luck, did no more than cursorily investigate with the managing agents of the defendants, the circumstances of the loss.

The bank's refinancing was capped at 67% of the security value of the shipowners' vessels, a value of US$50,225,000 (including the insurance value of the Good Luck of US$4,800,000), i.e. US$33,650,750. The refinancing was completed in July 1982 when the shipowners drew down the total loan of US$33,650,750, of which US$30,971,630 was used to pay off the existing loans, discharging the existing mortgages and the mortgage interest insurance. The balance of US$2,679,120 was used by the shipowners as additional working capital. On 4 August 1982, the defendants rejected the shipowners' insurance claim for the loss of the Good Luck. The bank called in the loans and as a consequence of inadequate security suffered a loss.

The case was a rich tapestry indeed for arguments as to causation; there was the fraudulent claim by the shipowners, the ineptitude of the bank, and the loss of the mortgagee interest insurance caused by the bank accepting a repayment of the original loans to the shipowner.

Hobhouse J gave judgment for the bank for the amount of the additional sum that the bank had allowed the shipowners to borrow on the basis that the insured value of the Good Luck was included within the calculation of the security value. The judge found that if the bank had been notified in writing that the ship was in a particular zone and therefore not covered by war risks, then the bank would have adopted a different approach to the refinancing - the insured value of the Good Luck would have been excluded from the calculation of security value reducing it to US$30,434,750.

As a consequence, the existing mortgage on the Good Luck would not have been discharged and the position under the mortgagee interest would have been preserved. The judge further found that the strong probability was that the whole matter of the Good Luck and any value to be attached to its hull or its insurances, would have been put on one side until the situation had been clarified and that would have meant that no draw-down in respect of working capital would have been permitted in July and August 1982.

In so finding, Hobhouse J rejected the defendant's submissions that the bank's own negligence was the sole cause of its loss. The judge apportioned blameworthiness in the proportion of two-thirds to the defendants and one-third to the bank. However, as the claim was in contract independent of negligence, he held that the bank's claim should not be reduced on the basis of contributory negligence. The Court of Appeal, reversing the decision on liability for breach, but not on the judge's findings as to causation, expressed agreement with Hobhouse J that if the defendant was in breach of the letter of undertaking, such breach would have been at least a cause of the bank's loss.

The Court of Appeal further stated that it would be clearly wrong in all the circumstances to hold that the bank's action amounted to a novus actus interveniens, breaking the chain of causation between the defendant's breach and the bank's loss. Finally, the Court of Appeal agreed with the judge's finding on the issue of contributory negligence.

The House of Lords, whilst reversing the Court of Appeal's decision on liability, concurred with both the judge's and the Court of Appeal's findings in the issues as to causation. Lord Goff stated:

‘The club sought to draw a distinction between the cause of the advance being made to the bank to Good Faith and the cause of the bank’s inability to recover the additional loan when it eventually sought to realise its securities. The latter, it was submitted, was the true proximate cause of any loss. With this submission I am unable to agree. On the findings made by the judge, the failure of the club to comply with its obligations left to the bank making an advance which was inadequately secured and which it would not otherwise have made, and the bank's loss was accordingly caused by the breach of the club's letter of undertaking. The club further submitted that what caused the advance was the bank's improvident decision to grant the further advance to Good Faith and/or the false assurances given by Good Faith to the bank, each of which was a novus actus interveniens. Again I do not agree with this submission, which is inconsistent with the concurrent findings of the judge and the Court of Appeal - findings with which I find myself to be in complete agreement.'

In Brown v KMR Services Ltd, Mr Brown, an underwriting name at Lloyds, brought claims against his member's agent for the agent's failure, on breach of contract and negligently, to warn Mr Brown of the dangers of excess of loss reinsurance, or advise on a proper spread of risk. The Court of Appeal considered the question of causation in relation to the giving of professional advice. The court held that where a member's agent was in breach of its duty to provide appropriate information and advice to a Lloyd's name, the question of causation was to be approached by identifying first what specific advice the name ought to have received and then what the name could prove, on the balance of probabilities, would have been the consequences of their receipt of such information and advice.

Where there are intervening events, as distinct from intervening acts, of the claimant or a third party, such events will not break the causal link between breach and damage if they were foreseeable. In Monarch Steamship Co Ltd v Karlshamms Hjesabrikes (A/B), the defendant ship owners chartered a ship to the plaintiffs for the carriage of a cargo from Manchuria to Sweden on terms that the voyage would be completed by July 1939.

In breach of the charter party the ship was unseaworthy, resulting in a delay to the voyage, and in September 1939, on the outbreak of World War II, the British Admiralty diverted the ship to Glasgow resulting in transhipment of the cargo to Sweden on neutral vessels involving additional cost. The court held that in July 1939 the parties to the charter party should have had in mind the possibility of the outbreak of war and should have foreseen the events that subsequently happened. Accordingly, the defendant was entitled to recover damages for breach of contract.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

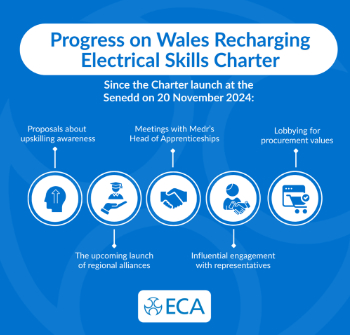

ECA progress on Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter

Working hard to make progress on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.

Many resources for visitors aswell as new features for members.

Using technology to empower communities

The Community data platform; capturing the DNA of a place and fostering participation, for better design.

Heat pump and wind turbine sound calculations for PDRs

MCS publish updated sound calculation standards for permitted development installations.

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.