Adversarial behaviour in the UK construction industry

|

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

The construction industry is often described as being ‘adversarial’, that is, it frequently involves conflict, opposition, confrontation, dispute and even hostility. Indeed, in her autobiography 'Open Secret', published in 2002, Stella Rimmington, the former Director General of MI5, wrote; '...the Thames House Refurbishment was fraught with difficulties. It was clear that dealing with the building industry was just as tricky as dealing with the KGB.'

The evidence of nearly 100 years of reports about the construction industry would seem to support this characterisation:

- Alfred Bossom’s book ‘Building to the Skies: The Romance of the Skyscraper’, published in 1934, was one of the first major criticisms of the performance of the UK construction industry. Bossom described an adversarial and wasteful industry in which construction took too long, was too expensive and was not satisfactory for its clients.

- The 1964 Banwell Report ‘The placing and management of contracts for building and civil engineering works’ recommended that the industry should develop less adversarial relationships.

- In his In 1994 report 'Constructing the Team' Sir Michael Latham notoriously described the construction industry, as; ‘ineffective’, ‘adversarial’, ‘fragmented’ and ‘incapable of delivering for its customers’.

- ‘Modernising Construction: Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General’, published by the National Audit Office in 2001 pointed to a ‘…tendency for an adversarial relationship to exist between construction firms, consultants and their clients and between contractors, sub-contractors and suppliers’.

[edit] How adversarial relationships have developed

There are a number of reasons for the adversarial nature of the industry:

- Construction projects tend to be one-offs. The project team may not have worked together before, they may not have worked on this sort of project before, and may not have time to build trust.

- Construction projects involve conflicting requirements and the co-ordination and integration of a great deal of complex information, procedures and systems.

- The industry is divided into a large number of professional ‘silos’ with little cross-discipline integration or collaboration.

- The traditional procurement route separates the client, designers, contractors and suppliers, with only legally-defined, bilateral contractual relationships between them.

- The supply chain has become more complicated and extended, leading to a greater number of contracts and so a greater chance of conflict.

- There is a tendency to use the UK legal system (which is inherently adversarial) to resolve disputes, rather than informal collaborative methods.

- Some traditional forms of contract are written in a way that is adversarial in nature, and they may only be referred to when problems arise.

- Lowest-cost bidding results in very small margins throughout the supply chain, and the successful bidders may then try to improve their financial position by making claims.

- There can be an inappropriate or unfair allocation of risk between the parties to contracts.

- The adoption of fast track construction techniques has left little margin for error and this can lead to disputes when problems arise.

- Inertia is prevalent in the industry and embedded cultural behaviours are difficult to change.

[edit] Possible solutions

A number of collaborative practices have been developed, providing mechanisms that encourage the project team to work together, rather than against one another, sharing risk and knowledge, facilitating collective learning and building trust:

[edit] Partnering

The Latham Report, recommended greater ‘partnering’ to combat the adversarial nature of the industry. Partnering is a broad term used to describe a collaborative management approach that encourages openness and trust. The parties to a contract become dependent on one another for success and this requires changes in culture, attitude and procedures throughout the supply chain.

Partnering is most commonly used on large, long-term or high-risk contracts. However, it can become a paper exercise unless there is proper buy-in throughout the supply chain, and ‘cosy’, inefficient relationships can develop. There is also some criticism that large partnering contracts can exclude smaller companies and so may hamper innovation.

For more information see: Partnering.

[edit] NEC

NEC was first published in 1993 as the New Engineering Contract. It is a suite of construction contracts intended to promote partnering and collaboration between the contractor and client and was developed as a reaction to other more adversarial, traditional forms of construction.

For more information see: NEC.

[edit] Alternative dispute resolution.

Rather than moving straight to litigation when conflicts arise, many construction contracts now provide for alternative dispute resolution procedures such as mediation, adjudication and arbitration.

Construction is also subject to statutory schemes which impose adjudication procedures in the absence of an appropriate contractual agreement, such as the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 and the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009.

For more information see: Alternative dispute resolution.

[edit] Selection criteria.

Suppliers can be selected based on criteria other than just the lowest cost. Alternative procedures include the Most Economically Advantageous Tender (MEAT), best value tendering and so on.

For more information see: Selection criteria.

[edit] Integrated supply teams.

The term ‘integrated supply team’ refers to the integration of the complete supply chain involved in the delivery of a project, including the main contractor, designers, sub-contractors, suppliers and so on. Providing services as one entity, rather than a plethora of disparate suppliers, creates a single point of responsibility for the delivery of a project, and binds the suppliers together to achieve a common objective.

For more information see: Integrated project team.

[edit] Fair payment practices

The Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 includes provisions to ensure that payments are made promptly throughout the supply chain.

Other fair payment practices include; publication of payment practices, project bank accounts, transparency regarding payment procedures throughout the supply chain, fair payment charters, proper release of retention, prevention of ‘pay when paid’ practices and so on.

For more information see: Fair payment practices.

[edit] Other collaborative practices.

Other working practices that can encourage collaboration include:

- Clear lines of communication and authority.

- Clear contract documents.

- Careful record keeping.

- Strict change control procedures.

- Early contractor involvement.

- Early engagement with suppliers.

- Co-location of team members and regular social activities.

- Regular workshops and team meetings.

- Problem resolution procedures based on solutions not blame.

- Early warning procedures.

- Collaborative design tools such as building Information modelling.

- Clash avoidance.

- Allocation of risks to those best able to control them.

- Open book accounting.

- Effective stakeholder management.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki,

- Alternative dispute resolution.

- BS11000 Collaborative business relationships

- Building Information modelling.

- Change control procedures.

- Claims.

- Clash avoidance.

- Collaborative practices.

- Collaboration: a quality management perspective.

- Conflict avoidance.

- Disputes.

- Early contractor involvement.

- Early warning.

- Fair payment practices.

- Fragmentation.

- Integrated project team.

- Integrated supply team.

- Latham Report.

- NEC.

- Open book accounting.

- Partnering.

- Partnering charter.

- Pressing pause to avoid errors.

- Selection criteria.

Featured articles and news

Scottish parents prioritise construction and apprenticeships

CIOB data released for Scottish Apprenticeship Week shows construction as top potential career path.

From a Green to a White Paper and the proposal of a General Safety Requirement for construction products.

Creativity, conservation and craft at Barley Studio. Book review.

The challenge as PFI agreements come to an end

How construction deals with inherited assets built under long-term contracts.

Skills plan for engineering and building services

Comprehensive industry report highlights persistent skills challenges across the sector.

Choosing the right design team for a D&B Contract

An architect explains the nature and needs of working within this common procurement route.

Statement from the Interim Chief Construction Advisor

Thouria Istephan; Architect and inquiry panel member outlines ongoing work, priorities and next steps.

The 2025 draft NPPF in brief with indicative responses

Local verses National and suitable verses sustainable: Consultation open for just over one week.

Increased vigilance on VAT Domestic Reverse Charge

HMRC bearing down with increasing force on construction consultant says.

Call for greater recognition of professional standards

Chartered bodies representing more than 1.5 million individuals have written to the UK Government.

Cutting carbon, cost and risk in estate management

Lessons from Cardiff Met’s “Halve the Half” initiative.

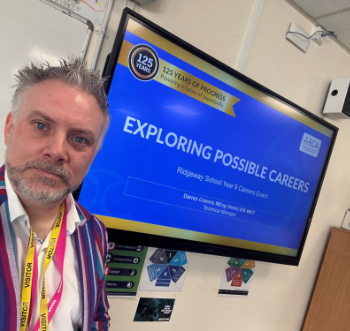

Inspiring the next generation to fulfil an electrified future

Technical Manager at ECA on the importance of engagement between industry and education.

Repairing historic stone and slate roofs

The need for a code of practice and technical advice note.

Environmental compliance; a checklist for 2026

Legislative changes, policy shifts, phased rollouts, and compliance updates to be aware of.