The building as climate modifier

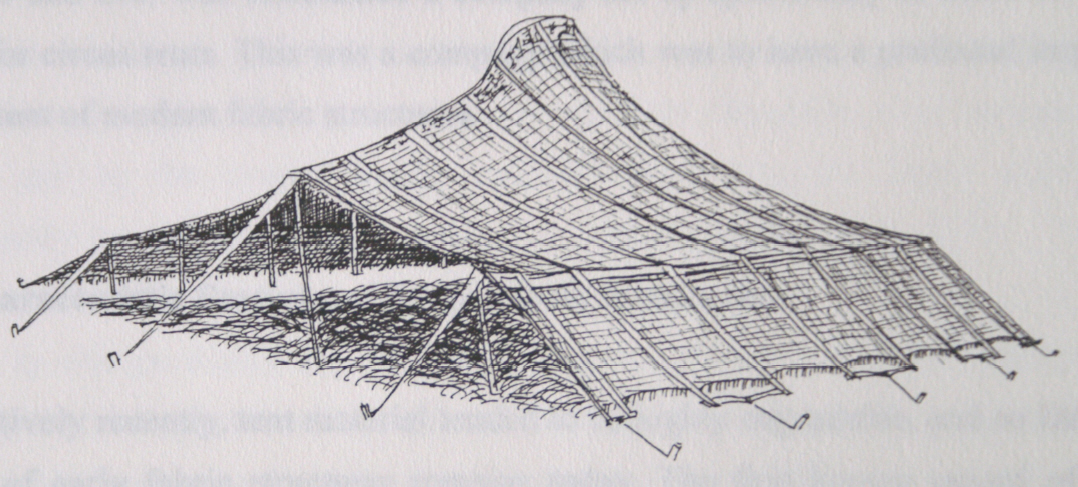

Remains have been found of simple structures constructed from animal skins draped between sticks dating back over 40,000 years, and it is likely these were the first type of shelter constructed by humans.

Simple tents suited a nomadic lifestyle. Lightweight and easy to carry, they could be moved from place to place in harsh environments where it was necessary to keep on the move to stay alive. Where resources were more plentiful, it was possible to settle down and build permanent shelters in the form of huts. In intermediate environments, a whole range of composite structures developed, part tent, part hut, most notably the Yurt, a demountable hut, still in use in places such as Mongolia today.

This combination of a fundamental requirement for shelter, moderated by practicality and resource availability, still drives the design of our buildings today, and can be seen in as varied typologies as the Troglodytic architecture of sculptured hillside landscapes in Morocco, to the Eskimos’ igloos, to Malaysian tree-dwelling, African courtyard houses, and the English thatched cottage.

In each case, the building fabric acts as a climatic modifier, controlling the extent to which conditions are able to transmit between the outside and the inside. This extent of modification depends on a wide range of factors, including; the materials used, their thickness and form, the way the elements fit together and interact, surface conditions, openings and so on.

In cold climates, buildings offer protection against the wind, rain, the cold, snow, and so on. Curved igloo shapes present the minimum surface area for the largest volume.

In hot and dry climates, there is more of a need for heavy mass buildings and shading. Shaded courtyards are common, and openings allow cross-ventilation. Thick adobe walls can be used to retain heat during the day and release it to the interior as temperatures cool at night. See Thermal mass for more information.

More complex features, such as trombe walls, use a combination of thermal mass and glazing to collect and store solar radiation so that it can be used to heat the interior.

The more effective the fabric of a building as a climatic modifier, the less energy will be required to make conditions within the building comfortable. See Passive building design for more information.

Very broadly, the environmental conditions that the fabric of a building might be required to modify include:

- Air temperature.

- Air movement.

- Humidity.

- Air quality.

- Noise.

- Solar radiation.

- Long wave infra red radiation.

- Visible light.

- Moisture.

However, there can be a conflict between the need for a building to act as a climatic modifier, and other performance requirements, such as privacy, security, access, views, and so on.

Requirements will also change with time of day. For example a building might be required to absorb heat during the day and then purge built up heat during the night. See night-time purging for more information. Similarly, conditions may be very different in the winter and the summer.

Additionally, the environmental conditions experienced by buildings are generally modified versions of the local climate. These microclimates can be affected by:

- Adjacent structures.

- Landscaping, such as trees.

- Topography.

- Local activities such as traffic or industrial processes.

This is a dynamic relationship that is also affected by other parts of the building itself, such as roof overhangs, tall elements, openings, and so on. For example, a roof overhang can be used to moderate the amount of rain that will fall on the wall below. Tall buildings can create wind tunnel effects at ground level, enclosing buildings can stifle air movement, buildings generally can contribute to the urban heat island effect, and so on.

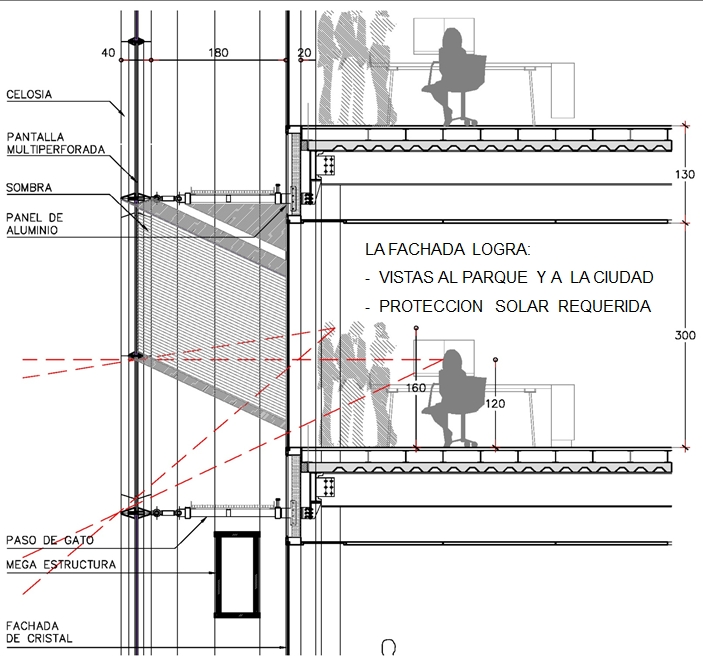

The design of buildings in order to satisfy all these requirements and to minimise the consumption of energy, has lead to increasingly complex dynamic façade designs which can include rainscreens, shading, glazing, thermal mass, insulation, cavities, vapour barriers and so on. This not only requires careful design, but also a high standard of workmanship during construction, in particular to ensure air tightness.

However, there is increasing evidence that buildings do not perform in practice as they were expected to when they were designed. This is for a number of reasons, including; over optimistic calculations, inaccurate modelling, poor detailing, incorrect specification, poor workmanship and a lack of understanding by occupants and operators. For more information see Performance Gap.

A range of standards have been developed to attempt to certify the standard of environmental performance of buildings, such as BREEAM and Passivhaus. Passivhaus suggest that, 'A Passivhaus is a building, for which thermal comfort can be achieved solely by post-heating or post-cooling of the fresh air mass, which is required to achieve sufficient indoor air quality conditions – without the need for additional recirculation of air.’

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Airtight.

- Building.

- Building fabric.

- Cooling systems for buildings.

- Dynamic façade.

- Façade.

- Heating.

- Passivhaus.

- Principles of enclosure.

- The history of fabric structures.

- The thermal behaviour of spaces enclosed by fabric membranes

- Thermal comfort.

- Thermal pleasure in the built environment.

- Trombe wall.

- Ventilation.

- Weathertight.

Featured articles and news

National Apprenticeship Week 2026, 9-15 Feb

Shining a light on the positive impacts for businesses their apprentices and the wider economy alike.

Applications and benefits of acoustic flooring

From commercial to retail.

From solid to sprung and ribbed to raised.

Strengthening industry collaboration in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Institute of Construction and The Chartered Institute of Building sign Memorandum of Understanding.

A detailed description fron the experts at Cornish Lime.

IHBC planning for growth with corporate plan development

Grow with the Institute by volunteering and CP25 consultation.

Connecting ambition and action for designers and specifiers.

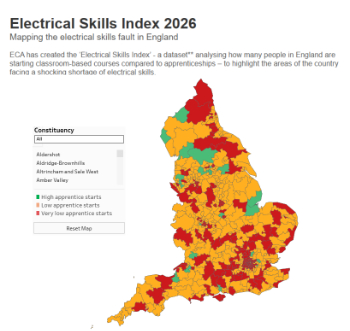

Electrical skills gap deepens as apprenticeship starts fall despite surging demand says ECA.

Built environment bodies deepen joint action on EDI

B.E.Inclusive initiative agree next phase of joint equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) action plan.

Recognising culture as key to sustainable economic growth

Creative UK Provocation paper: Culture as Growth Infrastructure.

Futurebuild and UK Construction Week London Unite

Creating the UK’s Built Environment Super Event and over 25 other key partnerships.

Welsh and Scottish 2026 elections

Manifestos for the built environment for upcoming same May day elections.

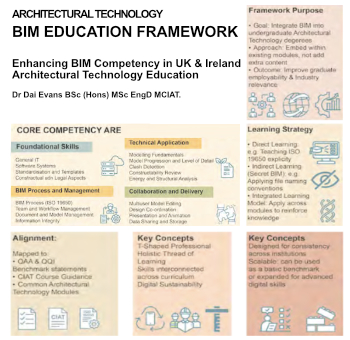

Advancing BIM education with a competency framework

“We don’t need people who can just draw in 3D. We need people who can think in data.”

Guidance notes to prepare for April ERA changes

From the Electrical Contractors' Association Employee Relations team.

Significant changes to be seen from the new ERA in 2026 and 2027, starting on 6 April 2026.

First aid in the modern workplace with St John Ambulance.

Solar panels, pitched roofs and risk of fire spread

60% increase in solar panel fires prompts tests and installation warnings.

Modernising heat networks with Heat interface unit

Why HIUs hold the key to efficiency upgrades.