The Blower Foundation

The construction drawings by which most buildings of the last 200 years have been built are at risk of being lost if they are not catalogued, recorded and safely stored.

|

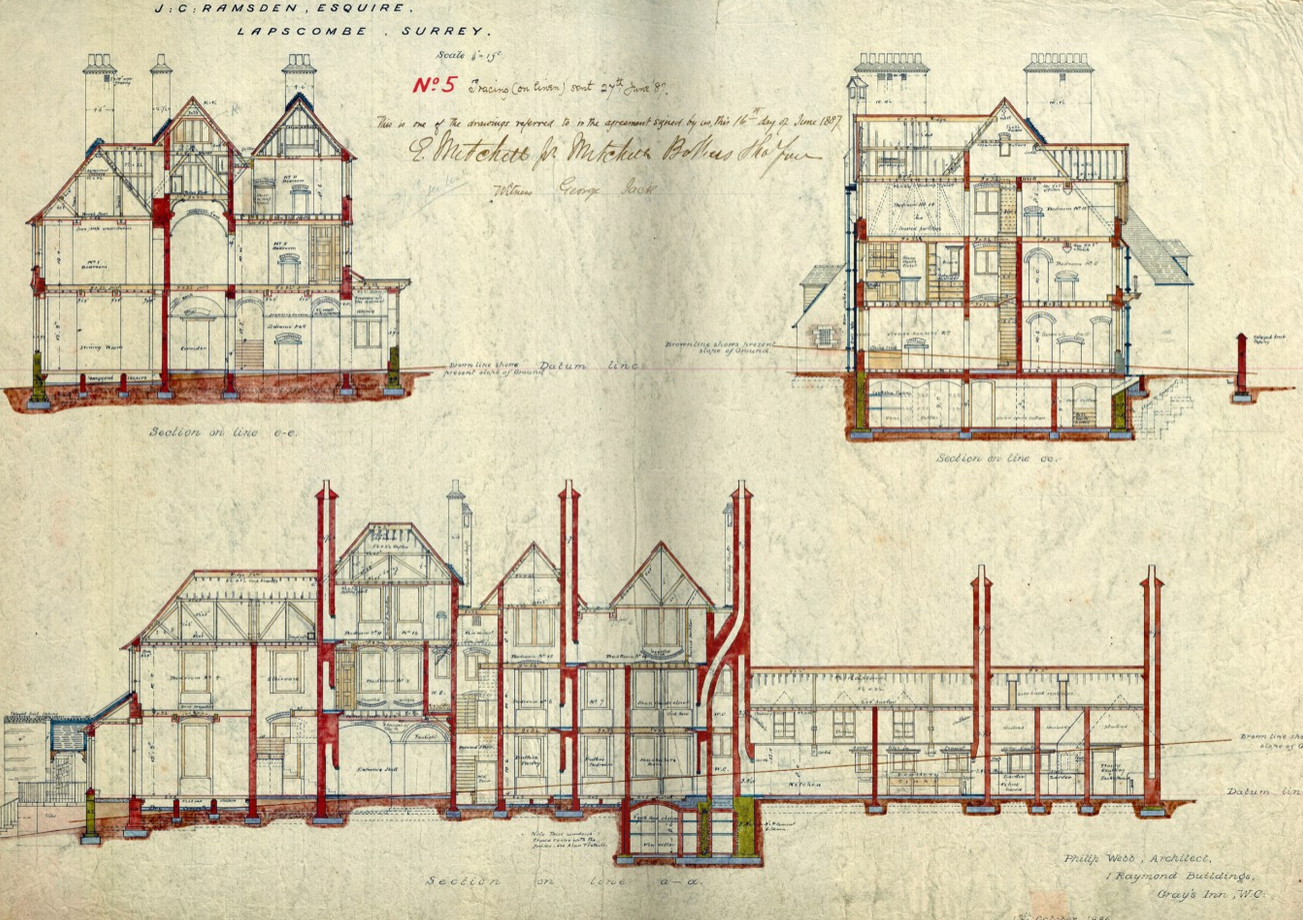

| Sections of a design for a house at Shamley Green, Surrey, drawn in 1886 by Philip Webb (1831–1915). |

We have consigned the drawing board and the set square to history, but in attics and storerooms all around the country lie rolls and boxes of drawings, sketches and blueprints equally beyond a useful life, unloved and gathering dust. Entire careers rest in these dark corners.

Over a handful of generations before us and in the not-so-distant past, the nation’s built fabric was largely remade, design skills professionalised and new ways of building evolved, including the wholesale use of technical drawing to guide the construction process. The post-18th-century British Isles we see today were largely first imagined and drawn on those drawing boards. Their records tell a story beyond the fabric of the building but once these archives of a career are gone, like any heritage asset, they are gone forever.

Stedman Blower Architects, a family practice in the fifth generation, is one such archive, filling three shipping containers with models, documents and drawings, the earliest dating back to 1895, spanning 125 years of the built history of one corner of England, in and around Lutyens country in the Surrey hills. They are beautiful objects in their own right. Not only do they tell stories, but those they tell are relevant today. The archive is a both a legacy and a burden, one repeated across the country.

If we accept that these documents have value, whose loss would be irretrievable, how do we manage the cataloguing and recording of them? What is the value to be attached to such records, both individually and as a collective? These are questions that the Blower Foundation (https://blowerfoundation.org) has set out to answer.

Established in 2003, the foundation has been slowly digitising the documents from Stedman Blower’s containers and making them available online. As the years have gone by and word has spread locally, the trustees have received other archives, one from another local family of eminent architects spanning from 1920 to 1980, and even the odd roll of drawings by building owners for cataloguing into the collection.

The foundation’s focus is, broadly, on architecture of general practice between the 19th to the 21st centuries. While there are big names in there – Detmar Blow, Philip Webb and Sir Edwin Lutyens – many of the drawings are by relatively unknown architects. Without the archive, these careers would become lost. Yet their impact on the world today is impressive. There are not just plans for grand homes, but for pubs, shops, housing estates and bus shelters. They are works of art, but also documentary evidence of a working life rooted in a community.

There is a practical application to this ceaseless searching and earnest recording. As architects, being able to quickly search for a building’s history and how it may have looked in an earlier iteration is enormously useful. The drawings could be used when writing heritage statements and in support of planning applications, while also enabling a body of projects to be collated to better understand local character, helping to build resilience against increasingly homogenised and global architectural culture.

Some of the drawing records were by some talented architects, who may or may not have ever been particularly commercially successful but were instrumental in shaping local landscape. The online archive in the public domain seeks to capture the architectural spirit of a place over time. A digitised archive on the internet will remain there forever.

Historically, fashion has been the enemy of drawings like this. The collection of drawings of Tudorbethan houses from the interwar period is rich, but while they are at the moment terribly unfashionable, they are important illustrations of a significant period in British domestic architecture. The same is true of many of the drawings of post-war suburban Britain, not brutalism or the international style, but at least in part a product of those developments. Architects or architecture need not be ignored just because they are unfashionable in 2022.

There is a strong vernacular tradition in these collections, reflected not just in style, but in materials, form and scale. Political consensus has shifted towards asking that new buildings might be best to respond to these local traditions, not by copying them but by expressing some of the same language. A humble house or a bus stop has relevance in architectural heritage as the background to our lives.

Stedman Blower approached the RIBA some moons ago. The institute said that it had no interest in this marginally important architectural archive and pointed instead towards a suitable local archive. The local (Farnham) Museum simply does not have the resources for such a large collection, being barely able to look after the material that it already has. For example, it has some surviving documents (a fraction) from the eminent 20th-century revivalist architect Harold Falkner, retrieved from a builder’s skip in the 1960s by a passing neighbour. These, never catalogued in 60 years, sit on a shelf in an attic under a leaky roof, with no security to prevent their loss. The local county records offices, Surrey in this case, might be interested in such an archive, but the archive might well get lost in their vaults and never see the light of day, let alone be available for researchers.

The Blower Foundation’s online database is basic, built at modest cost and from charitable donations over the years. The archive is in the public domain and free to access. The records exist in the digital domain in perpetuity, so a facsimile is saved if the originals are lost.

The trustees have worked in the past with a publicly funded and professionally managed archive database for the visual arts generally, VADS (https://vads.ac.uk), but each image or artefact needs to be recorded with a considerable number of data fields filled in. It is unwieldy and not for the average user. There is a place for a much simpler database, probably not to the taste of an archivist, but with a rather more wiki-type approach. It may be better to get the material up and available simply and easily, rather than painstakingly catalogued. The RIBA Collections, being a globally important archive, rightly take the archivist approach, but there is room for a cut-down archive database in parallel.

This article originally appeared as ‘Where will the drawings go?’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 174, published in December 2022. It was written by Damien Blower, the principal of Stedman Blower Architects and founding trustee of the Blower Foundation, the UK’s only privately funded charitable trust dedicated to the protection of architectural archives and records.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.

National Audit Office (NAO) says Government building maintenance backlog is at least £49 billion

The public spending watchdog will need to consider the best way to manage its assets to bring property condition to a satisfactory level.

IHBC Publishes C182 focused on Heating and Ventilation

The latest issue of Context explores sustainable heating for listed buildings and more.

Comments

[edit] To make a comment about this article, click 'Add a comment' above. Separate your comments from any existing comments by inserting a horizontal line.