Reversibility in conservation ethics

Although conservation works are evaluated with the force of law, future generations will judge our work not on the grounds of legality, but on whether it was the right thing to do.

By necessity, many of us working in building conservation are generalists. We are confronted every day with buildings of vastly different dates, construction methods, and social, urban and rural contexts. We have to master disparate subjects from geology to historic farming techniques, architectural theory to the compatibility of materials. Once acquired, this knowledge needs to be turned into workable advice and communicated. Interdisciplinarity is fundamental. Yet building conservation appears to have missed, or at least neglected, an important lesson from a close relative of our discipline: the conservation of paintings.

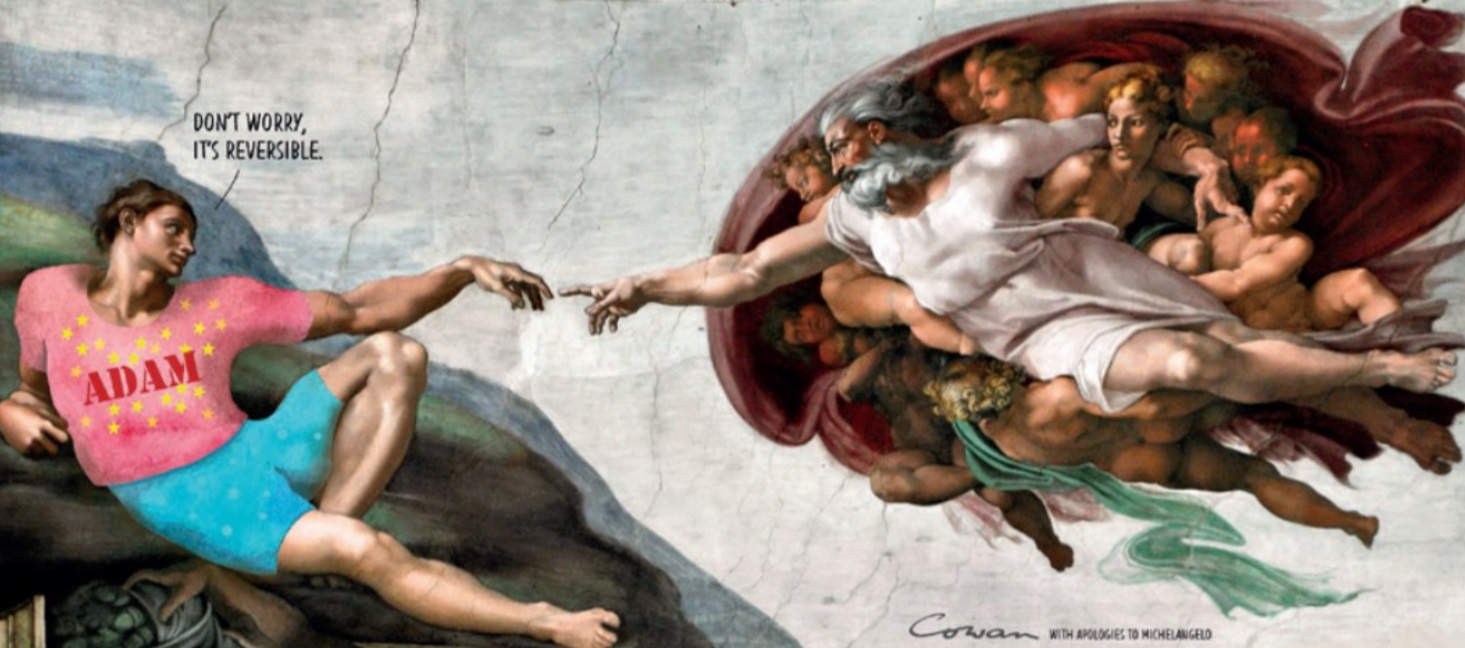

Conservators of easel and wall paintings alike are intimately familiar with the concept of reversibility. It is one of the most important elements of their conservation ethics. Some actions can be undone, while others cannot, and the ability to undo something when it comes to irreplaceable objects is obviously desirable. This is not chiefly because paintings conservators do not trust themselves not to make blunders. Rather, paintings conservators know that conservation practice has changed radically over the course of its short history, and will continue to.

What conservators did with zeal in the past, for example, stripping frescoes from walls and attaching them to canvases today seems like recklessness.[1] The process removes a work from its intended setting. In extreme cases, the original location of a work and its provenance can be totally lost as a result.[2] Moreover, the difficult procedure can easily be botched, partly or wholly destroying the paintings. What routine processes might be considered dangerous and unnecessary in the future? Moreover, what technologies might enable the same work to be done with less harm to the original object? Questions like these show the importance of reversibility. If an intervention can be undone, none of these considerations matter: a conservator can strip away the interventions they disagree with and the artefact keeps its integrity.

Reversible interventions are generally additive, rather than subtractive. Modern paintings conservators tend to use isolating layers of varnish to separate their retouching from the original work beneath. The layers can simply be dissolved in future, leaving the original work intact—no more, no less. For a similar reason, restorers almost never use oil paint when retouching an oil painting.[3] Otherwise, their work would bind to the existing paint film irrevocably: oil paint polymerises slowly to the point that it can no longer be easily dissolved. At this point, removing the conservator’s efforts with a powerful solvent would also obliterate the original work. Instead, conservators use paints which are compatible in solvents that are different to those of the original artefact. On oil paintings, synthetic polymers are often used which are soluble in polar (oil-repelling) solvents.

For paintings conservators, reversibility is important in retouching because retouching is a particularly visible and contentious topic. There are different approaches to retouching, such as the tratteggio or rigatini technique, where individual strokes of colour are broken up to highlight the difference between original and restoration. The thinking behind this will be familiar to buildings conservators, since it echoes ‘legibility’ and concern for the ‘authenticity’ of the original, a key tenet of the Venice Charter (itself under re-examination).[4] But ‘legible’ retouching is not always considered best practice. Other conservators will retouch paintings in a more mimetic way. There are a few different reasons one might favour concealed retouching. Some might consider their work to be minimal in extent: do we need to be ‘transparent’ about a pinhole of a background less than a millimetre in diameter being filled in? Others may view the visibility of their restoration to be a distraction, and that their primary aim is to make the subject matter readable again.

In important ways, the retouching of paintings is closely analogous to extending historic buildings (and to changes within the setting of a historic building). Both are additions to the original object. An extension adds to a building’s fabric, but it does not take away. It may increase its complexity, and change the way it is experienced. Yet because they are additive, extensions are reversible. This is just as important a distinction in buildings conservation as it is in the conservation of pictures. If a single six-panelled Georgian door is scrapped from a house, that house has lost some of its integrity forever. If an enormous, poorly designed extension is added to a house, the house has not lost its integrity. True, the latter intervention will be far more obvious, and perhaps more ‘harmful’ in building conservation parlance, but this is not the whole story. There is no walking back on one of these interventions, but there is hope for the other.

The distinction between reversible and irreversible change is fundamental, and cuts to the heart of conservation philosophy. It should also be a key practical consideration when evaluating change to historic buildings. Reversibility can help us assess what level of harm or enhancement is at play, and indeed what counts as harm in the first place. There will be a degree of subjectivity when thinking about the wisdom of adding a wing or porch to a building, but the loss of a wing or porch is a matter of fact. Reversibility is therefore conceptually distinct from the ‘amount’ of visual change at stake, and should be given due weight in conservation decision making.

Nowhere in primary legislation, or national planning policy, can ‘reversibility’ be found. For listed buildings, the legislation proscribes unauthorised ‘demolition, […] alteration or extension’ in the same clause without differentiation.[5] National planning policy also fails to recognise the concept of reversibility. Indeed, it explicitly equates development in the setting of a listed building (which is in principle reversible) with the outright demolition of a listed building. As paragraph 200 states, ‘any harm to, or loss of, the significance of a designated heritage asset (from its alteration or destruction, or from development within its setting), should require clear and convincing justification.’[6]

Equating demolition of a building with development in its setting, or additions to it, is not just philosophically troubling. A paintings conservator would probably be unsettled by the lack of distinction between reversible and irreversible interventions. But such a person would also be left without a vital yardstick for deciding what should and should not be done to a historic object. We are in this position, but we can change this by integrating discussions of reversibility into our work. An acknowledgement of different types of harm (irreversible, easily reversible, reversible in principle), as well as amounts of harm from policymakers and others would also be empowering and clarifying.

The suggestions and analogies made in this short article may seem bold, but if we do not think about our conservation ethics in an open and lively way, assumptions will go unchecked. The intense, sometimes downright fierce debates in the field of paintings conservation should be a salutary example: witness for example the sparring between Joyce Plesters and Ernest Gombrich about the ethics of varnish removal.[7] Gombrich’s position was that darkened varnishes, often considered a defect, were a deliberate feature of easel paintings (and that therefore should not be removed) due to some mentions of a dark ‘veil’ of varnish in some renaissance-era sources and in Pliny’s Natural History. Plesters, on the other hand, pointed out that the ‘dark’ varnish Pliny was referring to may have referred to its appearance in the bottle, and rattled off an impressive list of historical painting treatises in which deliberately dark varnishes fail to get a single mention. The controversy about whether varnish should be removed had at its heart a controversy about basic art historical facts and, in turn, which parts of a painting were valuable.

Arguments like these allow us to clarify our understanding of conservation, what we choose to preserve, and why. Paintings conservators are usually accountable only to the owners of paintings, or to museum boards of trustees. In the world of buildings conservation, we have a ‘higher power’ in the form of legislation and local authorities who evaluate conservation works with the force of law. But the presence of such legal bodies should not lead to complacency. Future generations will judge our work, not on the grounds of its legality, or whether it got permission, but if it was the right thing to do.

- [1] ICOMOS, ICOMOS Principles for the Preservation and Conservation/Restoration of Wall Paintings, www.icomos.org/en/what-we-do/focus/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/chartersand-standards/166-icomosprinciples-forthe-preservation-andconservationrestorationof-wall-paintings

- [2] Madden, B (2022) ‘Wall Paintings Transfer: a short history, and the experience as applied to ancient Egyptian paintings’, British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan, Issue 26

- [3] Stoner, JH and Rushfield, R (2020) The Conservation of Easel Paintings, 2nd edition, Routledge, London and New York

- [4] For example, see Matthew Hardy, ed. (2009) The Venice Charter Revisited: modernism, conservation and tradition in the 21st century

- [5] Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990, chapter 2, section 7

- [6] National Planning Policy Framework (2021)

- [7] Plesters, J (1962) ‘Dark varnishes: some further comments’, Burlington Magazine, November; Gombrich, EH (1963) ‘Controversial methods and methods of controversy’, Burlington Magazine, March

This article originally appeared in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 178, published in December 2023. It was written by Alfie Robinson, a heritage consultant based in Cornwall.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.

National Audit Office (NAO) says Government building maintenance backlog is at least £49 billion

The public spending watchdog will need to consider the best way to manage its assets to bring property condition to a satisfactory level.

IHBC Publishes C182 focused on Heating and Ventilation

The latest issue of Context explores sustainable heating for listed buildings and more.