Development of the law of negligence 1932 to 1988

[edit] Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Heller & Partners Ltd

It took from the case of Donoghue v Stevenson in 1932 until 1964 to extend the principle of the Donoghue decision to statements that were given negligently.

Advertising agents, Hedley Byrne, needed a reference from a banker as to the creditworthiness of a potential customer. They approached their bankers who sought the advice of merchant bankers who in turn reported to Hedley Byrne. The report was headed 'without responsibility' and said that the potential customer was good for ordinary business arrangements. Hedley Byrne proceeded with their contract and by reason of the customer not being good for ordinary business arrangements, lost a considerable sum of money. They sued the merchant bankers.

The House of Lords held that a person is liable for statements made negligently in circumstances where they know that those statements are going to be acted on and they were acted on. However, in this case, the merchant banker escaped liability by reason of having expressed their report to be without responsibility. This case may have assumed new importance since the decision in Murphy v Brentwood District Council.

See Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Heller & Partners Ltd for more information.

[edit] Dutton v Bognor Regis UDC and Another

The first major extension of the test of Lord Atkin in Donoghue v Stevenson in a building case was in 1972 in Dutton v Bognor Regis UDC and Another (now overruled by Murphy v Brentwood District Council).

A house was built on a rubbish tip and Mrs Dutton was the second owner of the house. The walls and the ceiling cracked, the staircase slipped and the doors and windows would not close; the damage was caused by inadequate foundations. Mrs Dutton sued the builder (with whom she settled before the hearing) and the local authority.

The Court of Appeal held that the local authority, through their building inspector, owed a duty of care to Mrs Dutton to ensure that the inspection of the foundations of the house was properly carried out and that the foundations were adequate, and that the local authority were liable to Mrs Dutton for the damage caused by the breach of duty of their building inspector in failing to carry out a proper inspection of the foundations.

Lord Denning MR said, applying Lord Atkins test:

‘I should have thought that the inspector ought to have had subsequent purchasers in mind when he was inspecting the foundations - he ought to have realised that, if he was negligent, they might suffer damage.’

The Dutton case was followed on this point in many subsequent and important cases: Sparham-Souter v Town & Country Developments (Essex) Ltd; Sutherland & Sutherland v C. R. Maton & Sons Ltd; Anns v Merton London Borough Council; Batty and Another v. Metropolitan Property Realisations Ltd and Others. However, as is often the case with changes in orthodoxy in the law, the seeds of destruction of this widening of the law of negligence were sown by a dissenting judgment, that of Stamp LJ in the Dutton case in 1972, but it was to take many more years before change came:

‘I may be liable to one who purchases in the market a bottle of ginger beer which I have carelessly manufactured and which is dangerous and causes injury to personal property; but it is not the law that I am liable to him for the loss he suffers because what is found inside the bottle and for which he has paid money is not ginger beer but water, I do not warrant, except to an immediate purchaser, and then by contract and not in tort, that the thing I manufacture is reasonably fit for its purpose. The submission is, I think, a formidable one and in my view raises the most difficult point for decision in this case. Nor can I see any valid distinction between the cases of a builder who carelessly builds a house which, although not a source of danger to personal property, nevertheless, owing to a concealed defect in its foundations, starts to settle and crack and becomes valueless, and the case of a manufacturer who carelessly manufactures an article which, though not a source of danger to a subsequent owner or to his other property, nevertheless owing to hidden defect quickly disintegrates. To hold that either the builder or the manufacturer was liable except in contract would be to open up a new field of liability the extent of which could not, I think, be logically controlled and since it is not in my judgment necessary to do so for the purposes of this case, I do not more particularly because of the absence of the builder, express an opinion, whether the builder has a higher or lower duty than the manufacturer.’

In 1978, the position altered again with Anns v Merton London Borough Council.

[edit] Anns v Merton London Borough Council

Lessees of flats claimed against a local authority in negligence in relation to the local authority's powers of inspection under the by-laws in that, it was said, they had allowed the contractors to build foundations in breach of the by-laws, with resulting damage to the flats.

In a passage in his speech, which later became the excuse for a far-reaching and dramatic expansion of the circumstances in which a duty of care might be held to exist, Lord Wilberforce said in the House of Lords:

'Through the trilogy of cases in this House, Donoghue v Stevenson, Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Heller & Partners Ltd and Home Office v Dorset Yacht Co Ltd, the position has now been reached that in order to establish that a duty of care arises in a particular situation it is not necessary to bring the facts of that situation within those of previous situations in which a duty of care has been held to exist. Rather the question has to be approached in two stages. First one has to ask whether as between the alleged wrongdoer and the person who has suffered the damage there is a sufficient relationship of proximity or neighbourhood such that, in the reasonable contemplation of the former, carelessness on his part may be likely to cause damage to the latter in which case a prima facie duty of care arises. Secondly, if the first question is answered affirmatively, it is necessary to consider whether there are any considerations which ought to negative, or to reduce or limit the scope of the duty or class of person to whom it is owed, or the damage to which a breach of it may give rise.’

[edit] Junior Books Ltd v Veitchi Co Ltd

The development and extension of the law of tort probably reached its climax in the House of Lords in Junior Books Ltd v Veitchi Co Ltd in 1983. That case was on appeal to the House of Lords from Scotland.

Specialist flooring sub-contractors had laid a floor at the employer's factory and it was said by the employers that the floor was defective. The employers, who were not in contract with the sub-contractor, brought an action in delict (which is substantially the same cause of action in Scotland as negligence is in England). Despite the absence of any allegation by the employer that there was a present or imminent danger to the occupier (an essential ingredient of the Anns v Merton London Borough Council decision), the employers succeeded in their argument that the sub-contractor owed them a duty of care in negligence and that the sub-contractor was in breach of that duty.

It was said that there was a close commercial relationship between the employers and the sub-contractors. It is that justification for the decision which had led to enormous difficulties in the minds of those closely involved with the construction industry - after all, what is unusual about an employer engaging a contractor who in turn engages sub-contractors.

[edit] Muirhead v Industrial Tank Specialists Ltd

Notwithstanding these difficulties, Goff LJ in Muirhead v Industrial Tank Specialists Ltd felt able to say of the Junior Books decision:

'Faced with these difficulties it is, I think safest for this court to treat Junior Books as a case in which, on its particular facts, there was considered to be such a very close relationship between the parties that the defenders could, if the facts as pleaded were approved, be held liable to the pursuers.’

By 1983 architects, engineers, contractors and sub-contractors were at risk as to claims in negligence from a fairly wide range of potential plaintiffs. These included not only the people with whom they were also in contract such as the developer, but also subsequent owners and occupiers, including tenants and sub-tenants. The criticism of this state of the law began to mount, particularly from the construction professions.

[edit] Governors of the Peabody Donation Fund v Sir Lindsay Parkinson & Co Ltd

The first steps on the road to retrenchment in the law of tort came with Governors of the Peabody Donation Fund v Sir Lindsay Parkinson & Co Ltd in 1985. It was alleged in the case that the local authority owed a duty to Peabody in relation to drains, which had to be reconstructed after they were found to be unsatisfactory.

Lord Keith said:

'The true question in each case is whether the particular defendant owed the particular plaintiff a duty of care having the scope which is contended for, and whether he was in breach of that duty with consequent loss to the plaintiffs. A relationship of proximity in Lord Atkin's sense must exist before any duty of care can arise, but the scope of the duty must depend on all the circumstances of the case.'

In relation to Lord Wilberforce's two-stage test in Anns v Merton London Borough Council, Lord Keith also said:

'There has been a tendency in some recent cases to treat these passages as being themselves of definitive character. This is a temptation which should be resisted.’

[edit] Leigh & Sillivan Ltd v Aliakmon Shipping Co Ltd

Of the same passage in Anns v Merton London Borough Council, Lord Brandon continued the retreat in Leigh & Sillivan Ltd v Aliakmon Shipping Co Ltd in 1986:

'The first observation which I would make is that the passage does not provide, and cannot in my view have been intended by Lord Wilberforce to provide, a universally applicable test of the existence and scope of a duty of care in the law of negligence.’

[edit] Curran and Another v Northern Ireland Co Ownership Housing Association Ltd and Another

The retreat from Anns v Merton London Borough Council continued in Curran and Another v Northern Ireland Co Ownership Housing Association Ltd and Another in 1987 where the court refused to hold that the Northern Ireland Housing Executive owed a duty of care to future owners of a house to see that an extension had been properly constructed.

The three cases, Peabody, Aliakmon, and Curran have been referred to as the 'retreat from Anns' but in Yuen Kun Yeu v Attorney General of Hong Kong in 1987, the two-stage test of Lord Wilberforce in Anns was probably put to rest by Lord Keith. Further, in Simaan General Contracting Co v Pilkington Glass in 1988, the Court of Appeal held that a supplier of glass units for a new building, who had no contractual relationship with the main contractor and had not assumed responsibility to that contractor, was not liable in tort for foreseeable economic loss caused by defects in the units where there was no physical damage to the units, and the contractor had no proprietary or possessory interest in the property.

It follows from all this that the extensive duties in tort that had been developed in the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s were in some disarray by 1988. The whole basis of the decision in Anns had received widespread criticism and it was inevitable that sooner or later a challenge was mounted in the House of Lords to their previous decision in Anns. The first opportunity was in D&F Estates Limited and Others v Church Commissioners for England and others in 1988.

See D&F Estates Limited and Others v Church Commissioners for England and others.

[edit] Find out more

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

British Architectural Sculpture 1851-1951

A rich heritage of decorative and figurative sculpture. Book review.

A programme to tackle the lack of diversity.

Independent Building Control review panel

Five members of the newly established, Grenfell Tower Inquiry recommended, panel appointed.

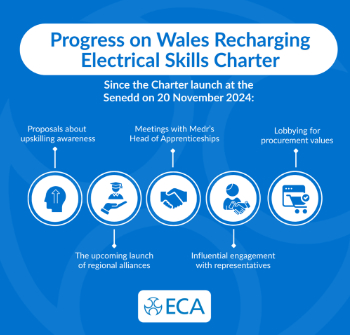

Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter progresses

ECA progressing on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.