British Architectural Sculpture 1851-1951

|

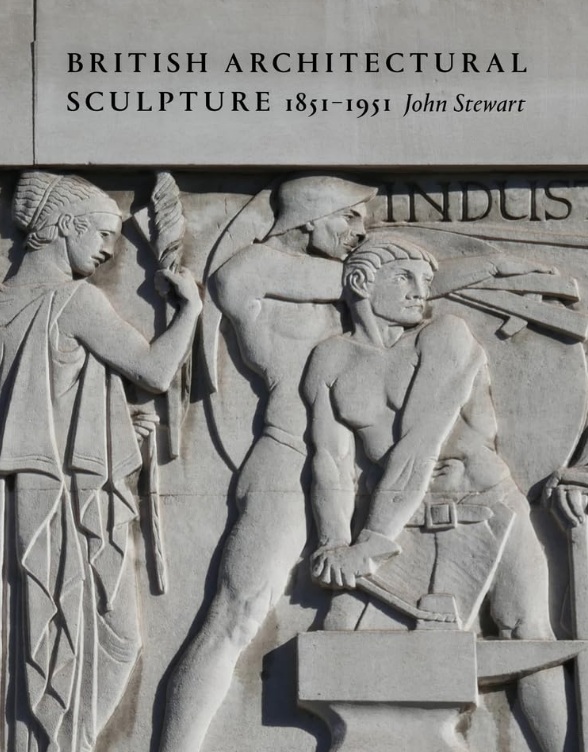

| British Architectural Sculpture 1851–1951, John Stewart, Lund Humphries, 2024, 208 pages, 151 colour and black-and-white illustrations, hardback. |

The subject of this well-produced and beautifully illustrated survey is the rich heritage of decorative and figurative sculpture adorning British architecture. Some of the works described have been covered in pioneering books about 19th-century sculpture by Susan Beattie and Benedict Read, and tangentially in books about architecture; but this is the first to focus purely on architectural sculpture for its own sake. Although Stewart has not written a catalogue or gazetteer (probably an impossible task given the sheer amount of sculpture on British buildings), simply by amassing in one book so many important examples, he has saved us a lot of shoe leather.

Stewart begins in 1851, but this is not an especially important date for architectural sculpture. For the real beginning of his story, he has to go back to the 1840s with the new Palace of Westminster and its vast amount of architectural ornament – capitals, bosses, gargoyles, heraldic achievements and statues – proliferating all over the building, setting the pattern for secular buildings of the gothic revival (churches are all but absent from the book). In the following chapters Stewart describes a succession of major civic and commercial buildings, and the sculptures that adorn them.

Up to the late 1870s and early 80s there was little collaboration between architects and fine art sculptors, whose principal output was freestanding pieces such as statues, busts and ‘ideal’ subjects (mythology, allegory and history). Architectural sculpture was produced by firms of masons such as Farmer and Brindley, or Thomas Earp. Stewart also draws attention to the work of less familiar firms, such as Richard Lockwood Boulton and Sons of Birmingham, J and G Mossman of Glasgow, and Robert Mawer of Leeds; of particular interest in today’s art-historical climate is Mawer’s wife, Catherine, a skilled stone carver, whose work can be seen at Leeds Town Hall.

Another welcome feature of the book is the technical material about the processes of making. Stewart explains, for example, that architects such as Barry or Burges provided sketches from which skilled craftsmen made clay models; plaster casts were then made and given to the stone carvers to copy. It is not clear how much freedom was given to the carvers, but they had to work within an idiom closely defined by the architects. This changed completely in the late Victorian period with the coincidence of two movements: first, the New Sculpture, when a new generation of fine-art sculptors turned away from the rigid constraints of neoclassicism, and adopted richer and more realistic styles; and, second, the arts-and-crafts movement, which promoted the unity of the arts, seeking to bring together practitioners of the different art forms as equals.

Stewart instances the formation of the Art Workers Guild (1884) as a key moment: its members included painters, architects, designers, sculptors and craftsmen. The new tone was set by the Institute of Chartered Accountants Hall, a baroque design by John Belcher, who gave artistic freedom to his sculptors, including Hamo Thornycroft and Harry Bates. Architects of the late Victorian and Edwardian baroque, and of the beaux-arts buildings that followed, collaborated with talented sculptors such as FW Pomeroy, William Goscombe John, Alfred Drury and George Frampton, who produced works of great power and expression, working in bronze as well as stone. In the inter-war period, architectural detail of all kinds was simplified and sculpture on buildings became less common, although major figures such as Jacob Epstein and Eric Gill produced important (and often controversial) works for buildings such as the London Underground Headquarters and Broadcasting House.

Just as the book begins with the Great Exhibition of 1851, it closes with the 1951 Festival of Britain. But the story extends beyond 1951, and in an epilogue, Stewart instances William Mitchell’s textured panels of precast concrete and Alexander Stoddart’s neoclassical reliefs as continuing the tradition.

We learn much about the training of sculptors and the varied nature of their collaborations with architects. Stewart also gives us a fair amount of purely architectural history, perhaps more than is strictly necessary, as much of it will be known to readers. He describes some buildings in excessive detail, and throughout the book there are passages of historical background which could also have been abbreviated: they are too general to relate directly to the very particular phenomenon of architectural sculpture. Nevertheless, this book is an enjoyable read for anyone who loves sculpture or architecture of the period.

This article originally appeared as ‘A continuing tradition’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 181, published in September 2024. It was written by Julian Treuherz, art historian and curator.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Conservation.

- Bas-relief.

- Conservation.

- Controversial statues.

- Heritage.

- Historic environment.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Life and death at Highgate Cemetery.

- Scagliola.

- Sculpture and architecture in a building.

- The Burrell Collection.

- The effigy of Blanche Mortimer.

- Trompe l'oeil murals.

- Worcester sculptor William Forsyth.

IHBC NewsBlog

IHBC Context 183 Wellbeing and Heritage published

The issue explores issues at the intersection of heritage and wellbeing.

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.

National Audit Office (NAO) says Government building maintenance backlog is at least £49 billion

The public spending watchdog will need to consider the best way to manage its assets to bring property condition to a satisfactory level.