Bronze

|

These late Bronze Age tools date from approximately 1000 to 800 BCE. They were found at Adabroc, Isle of Lewis in Scotland. |

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Alloys are impure substances (admixtures) comprising a mixture of metals - or a metal to which small additions of other metals and non-metals - have been added to give it specific desired properties. The result is a compound that is likely to be superior in performance to the pure metal and may be more economical in use.

Creating an alloy may produce enhanced tensile strength, ductility, malleability, corrosion resistance and so on. The resulting alloy may retain many of the properties of the original metal, such as electrical conductivity, in addition to the new properties.

[edit] The composition of bronze

Bronze is an alloy made from a mixture of copper and tin. It is one of the best known and oldest copper alloys.

Modifications to the proportions of copper and tin can result in types of bronze with different characteristics. In some instances, lead, zinc, manganese, aluminium, nickel and other materials may be added to enhance the hardness and flexibility of bronze alloys.

Unlike brass, which is a copper alloy that always contains some form of zinc, bronze only sometimes contains zinc.

[edit] History

The discovery of bronze dates to the Bronze Age - a period of history where humans moved away from working solely with stone to produce objects such as weapons and tools. While the precise dates of the Bronze Age vary in different parts of the world, evidence in the UK indicates the start as roughly 2500 BCE. This corresponds to dates associated with the introduction of metalworking as a skill.

The use of metals was not entirely unknown prior to the Bronze Age, but metal objects from earlier periods were usually made from a single type of metal. These objects were not particularly well suited for tasks that required durability.

During the Bronze Age, the discovery of the smelting process allowed humans to combine copper and tin to produce bronze - a much harder metal alloy. The durability of the substance has been reflected in the numerous bronze artefacts of the period that have survived.

It was during the Bronze Age that burial mounds or ‘round barrows’ became more common. These personal graves sometimes included objects made of bronze.

The mining of copper and the acquisition of tin resulted in the development of noteworthy bronze metalworking skills that produced fine tools and other durable implements. Where these skills progressed, farming based cultures increasingly began to rely on hunting based activities to supplement their food supplies. This resulted in the increased production of a wide range of weapons and tools such as axes, knives, spears and daggers, as well as ornamental items such as rings, beads, pins and bracelets.

The Bronze Age is believed to have lasted in the UK until roughly 700 BCE, which marked the beginning of the Iron Age. While iron was considered a stronger material in most circumstances, bronze was still preferred in applications where corrosion resistance was a priority. This was particularly true in instances where moisture - such the combinations of salt water and maritime objects or rainwater and public statuary - would be an ongoing concern.

[edit] Bronze in the modern age

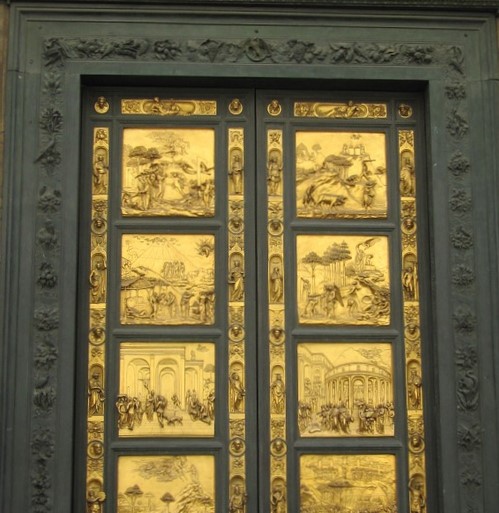

The popularity of bronze has continued through the centuries. It is regularly used to cast sculptures and is often incorporated into doorways, columns, commemorative plaques and other decorative components.

|

These gilded bronze doors in Florence were designed by the sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti for the north entrance of the Baptistery of San Giovanni in Florence. |

Its durability and corrosion resistant qualities also make bronze a common material in the production of hardware, springs, furniture trim, coins and so on. Bronze demonstrates high levels of thermal and electrical conductivity while being non-magnetic, which makes it suitable for use as tools (such as hammers, mallets, axes, and wrenches) in situations where the creation of sparks could be a safety issue.

[edit] Working with bronze

Bronze can be very hard to work by hand and is frequently used as a cast metal because its melting point is so low. When molten, bronze has great fluidity, so that even the most complicated details can be reproduced. Its contraction upon cooling is very slight, so there is little distortion.

When cold, the cutting edges of bronze can be tempered by hammering, which sharpens and strengthens it. It is often finished by hand. The value of antique bronze objects is often influenced by the quality of this type of hand work.

Bronze ages, acquiring a patina that can add shadows and textures. Skilled bronze workers can also achieve this effect deliberately through a process called patination.

When cleaning bronze, it is inadvisable to remove the patina unless absolutely necessary. Strong cleaners or excessively bright polishes should be avoided.

Despite its durability, bronze can corrode over time, particularly if it is exposed to high levels of air pollution. The patina eventually forms the familiar pale green copper carbonate which can partially prevent additional corrosion.

|

Bronze can also be damaged due to excessive human contact, flaws in the casting process or cracks caused by extreme weather or inhospitable climates.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

Featured articles and news

Building Safety recap January, 2026

What we missed at the end of last year, and at the start of this...

National Apprenticeship Week 2026, 9-15 Feb

Shining a light on the positive impacts for businesses, their apprentices and the wider economy alike.

Applications and benefits of acoustic flooring

From commercial to retail.

From solid to sprung and ribbed to raised.

Strengthening industry collaboration in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Institute of Construction and The Chartered Institute of Building sign Memorandum of Understanding.

A detailed description fron the experts at Cornish Lime.

IHBC planning for growth with corporate plan development

Grow with the Institute by volunteering and CP25 consultation.

Connecting ambition and action for designers and specifiers.

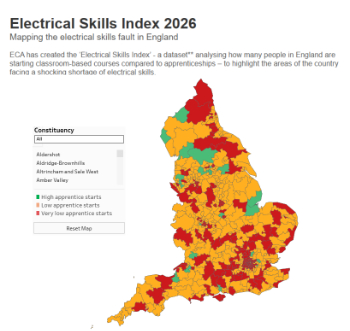

Electrical skills gap deepens as apprenticeship starts fall despite surging demand says ECA.

Built environment bodies deepen joint action on EDI

B.E.Inclusive initiative agree next phase of joint equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) action plan.

Recognising culture as key to sustainable economic growth

Creative UK Provocation paper: Culture as Growth Infrastructure.

Futurebuild and UK Construction Week London Unite

Creating the UK’s Built Environment Super Event and over 25 other key partnerships.

Welsh and Scottish 2026 elections

Manifestos for the built environment for upcoming same May day elections.

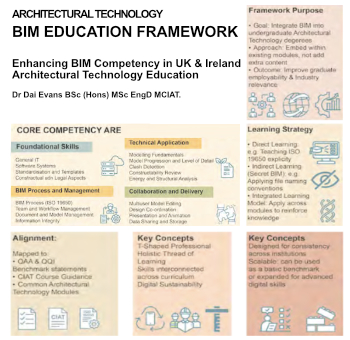

Advancing BIM education with a competency framework

“We don’t need people who can just draw in 3D. We need people who can think in data.”

Guidance notes to prepare for April ERA changes

From the Electrical Contractors' Association Employee Relations team.

Significant changes to be seen from the new ERA in 2026 and 2027, starting on 6 April 2026.

First aid in the modern workplace with St John Ambulance.

Solar panels, pitched roofs and risk of fire spread

60% increase in solar panel fires prompts tests and installation warnings.

Modernising heat networks with Heat interface unit

Why HIUs hold the key to efficiency upgrades.