Citigroup Center

The Citigroup Center's angled roof is seen behind The Lipstick Building, which was designed by John Burgee Architects with Philip Johnson.

The Citigroup Center's angled roof is seen behind The Lipstick Building, which was designed by John Burgee Architects with Philip Johnson.

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

The Citigroup Center (originally referred to as Citicorp Center but now known as 601 Lexington Avenue) is one of New York City’s many skyscrapers. Its angled top gives it an iconic appearance that helps it stand out from other buildings in that part of the Manhattan skyline, but its unusual base and invisible engineering are other characteristics that distinguish it from other buildings.

[edit] The church issue

What is not visible about this building is a series of engineering errors that could have been one of the biggest disasters in modern architectural history - all because of a church.

In 1970, architect Hugh Stubbins came up with plans for the 59-story glass and metal clad tower for First National City Bank (later known as Citigroup). There was one problem with the site that had been selected - an existing church had to be accommodated in the plans in order for the purchase of the site to be approved. The decision was made to demolish the old church and rebuild it in the same location in a manner that would comply with the wishes of the congregation.

This view shows the entrance to the Lexington Avenue subway complex in East Midtown Manhattan. St Peter's Lutheran Church is the angle topped structure pictured in the left of the image.

The structural engineer William LeMessurier created a solution - four stilt-like columns that would support the massive structure at the centre of each side rather than at its corners. A fifth supporting column at the central core of the building was located at the elevator shaft.

Meanwhile, the newly built, freestanding St Peter's Lutheran Church would remain in its original location but tucked under the cantilevered corner of the new skyscraper that would be built above and around it. At no point would columns or supports for the skyscraper be permitted to go through the church.

[edit] The stilt solution

At roughly nine stories high, the 'stilts' created a possible issue with stability for the high rise building. To address this problem, LeMessurier designed a chevron shaped exoskeleton system of giant braces that would redistribute the building’s weight securely down to the stilts.

While the braces helped to redistribute the weight, they would also make the building too light for its height, thus it would sway during extreme weather conditions accompanied by high winds. This is not an unusual occurrence for New York City, which can experience hurricanes in the autumn and nor'easters in the winter.

To correct this issue, an electrically operated tuned mass damper (weighing 350 metric tonnes) was installed at the top of the building. This would act as a counterbalance against strong winds and keep the building from swaying.

[edit] Potential for disaster

The building was completed in 1976 and opened in 1977, but in 1978, a new (but not really new) problem was uncovered.

A civil engineering student at Princeton University had studied the building for her undergraduate thesis and realised calculations for its wind load only took into account perpendicular winds (north, south, east, west) but not quartering winds (northeast, northwest, southeast, southwest). Both types of wind load considerations were mandatory according to New York City’s building codes, and recalculations were required.

This data revealed a major design flaw with the joints of the chevron bracing - they would struggle to support the building from a strong quartering wind. This problem was made even worse due to an issue with the joints. The builder had switched from welded joints to bolted joints as a cost cutting measure. The decision was approved by LeMessurier’s firm but without his direct knowledge.

The cost cutting measure meant that hurricane force quartering winds above 75 miles per hour could shear bolts and compromise joints that had not been welded. Under those conditions, the chevrons would struggle to hold the building up.

The situation would be further compromised by a power outage - something that often happens during hurricanes. A blackout would render the electrical mass damper inoperable and the building would sway dramatically. The inadequate bolts would be subject to even greater stress.

In one additional calculation error, LeMessurier discovered that New York City’s truss safety factor of 1:1 had been used by his firm instead of the 1:2 column safety factor. Based on this combination of errors, the decision was made to correct the situation immediately - but in secret.

[edit] Structural remediation

Only key personnel and first responders were made aware of the repairs. The undertaking was given the code name Project SERENE (short for Special Engineering Review of Events Nobody Envisioned).

For three months, the general public and those who worked in the building did not know about the remediation activities. Welders were brought in from across the country to fix steel plates over all of the bolted joints, but they could only work in the evenings. Meanwhile, weather experts kept a close watch on the upcoming hurricane season.

The story was kept quiet until 1995, when a magazine article uncovered how the public had been unaware of the dangerous situation. It also raised a serious issue over professional ethics and the practice of architecture.

[edit] Citigroup no more

In 2001, Citigroup moved out of the building and sold much of its remaining interest to Boston Properties. The building was then renamed 601 Lexington Avenue.

Additional structural remediation work was performed on the building in 2002 in response to the attacks of 9/11. Blast resistant shields and additional steel bracing were added to one of the columns as protection against possible terrorist activity.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- American architecture and construction.

- Empire State Building.

- Ethics and the engineer.

- Ethics in construction.

- Exoskeleton.

- Flatiron Building.

- Heroic architecture.

- High-rise building.

- Managing and Responding to Disaster.

- Skyscraper.

- Truss.

- Using springs in construction to prevent disaster.

[edit] External resources

- AIA Trust, LeMessurier Stands Tall: A Case Study in Professional Ethics by Michael J Vardaro, Esq.

- National Academy of Engineering, William LeMessurier-The Fifty-Nine-Story Crisis: A Lesson in Professional Behavior (video of LeMessurier lecture from 1995).

- New Yorker, The Fifty-Nine-Story Crisis by Joseph Morgenstern.

Featured articles and news

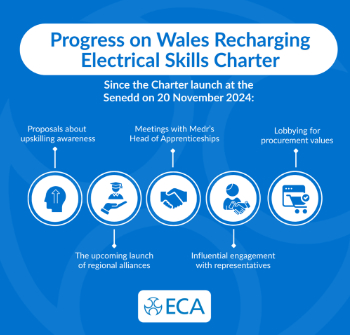

ECA progress on Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter

Working hard to make progress on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.

Many resources for visitors aswell as new features for members.

Using technology to empower communities

The Community data platform; capturing the DNA of a place and fostering participation, for better design.

Heat pump and wind turbine sound calculations for PDRs

MCS publish updated sound calculation standards for permitted development installations.

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.