The Commons: City of London

• Animation showing City of London predicted skyline by 2030, with the 11 new office blocks expected to be built: 1) 2-3 Finsbury Avenue; 2) 6-8 Bishopsgate; 3) 1 Leadenhall Street; 4) 1 Undershaft; 5) 100 Leadenhall Street; 6) 40 Leadenhall Street; 7) 70 Gracechurch Street; 8) 55 Gracechurch Street; 9) 50 Fenchurch Street; 10) 85 Gracechurch Street; 11) 55 Bishopsgate. Photographs: City of London/GMJ - Animation by Norman Fellows

- "Although the city office block may be a product of greed and stupidity, its causation is ignorance—far more serious."

- Cedric Price, ECHOES, 1969.

Contents |

[edit] FOREWORD

This article is the last item in a series of articles by Norman Fellows created in response to the challenge posed by the increasing dominance of the office building in major urban areas throughout the world. Its purpose is to prompt a serious questioning of the office building's medium and long-term usefulness.

[edit] INTRODUCTIONTo introduce this article the lead images from the preceding articles are pictured right in chronological order:—

Thus this article asks the following questions:— (1) "What is the relation between 'The Commons' and the 'City of London'?". (2) "How are the 'City of London' and design linked?" (3) "What is the conclusion?" |

|

• Introductory table with links to earlier articles in this series.

[edit] (1) "What is the relation between 'The Commons' and the 'City of London'?"

The first point about this article is the title — 'The Commons: City of London'. It assumes:—

- ... that there is some relation between 'The Commons' and the 'City of London'.

Wikipedia contains various definitions of each term in the following articles:—

- 'Commons'; [1]

- 'City of London'. [2]

Thus this article indicates:—

- .... that the relation between 'The Commons' and the 'City of London' is a power relation.

However, Michel Foucault has introduced the concept of governmentality which may be defined as the "art of government" - see Note [3] for a fuller definition by Foucault and an examination of it. According to Wikipedia:—

- "The concept of "governmentality" develops a new understanding of power."

- Wikipedia (2023) 'Governmentality'. [3]

BC 300,000 plus BC 300,000 plus

|

"In the beginning, the commons was everywhere. Humans roamed through it, hunting and gathering to meet their needs. Like other species, we had territories but these were communal to the tribe, not private to the person." Peter Barnes (2014) [4] |

• Around 100,000 years ago, we began migrating across the globe. | |

BC 55,000 BC 55,000

|

• Our population remained low — probably less than 1 million people. |

• With the advent of farming, growth picked up |

• By AD 1, world population reached approximately 170 million people |

• Table 1: Thumbnails of selected frames from 'Human Population Through Time'. Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History. [5]

Further to the text referenced in Note [3]:—

- "Governmentality" applies to a variety of historical periods and to different specific power regimes."

- (ib.)

For example, governmentality applies to the following periods of power regimes in the City of London:—

- Roman - c.43-410;

- Medieval - c.1154-1485;

- Stuart - 1603-1714.

The effect of these periods is indicated chronologically from left to right in Table 2.

|

AD 200-500 • 'Londinium' |

AD c.1300 • 'Medieval era' |

Central London in 1666, with the burnt area shown in pink and outlined in dashes (Pudding Lane origin marked with a green line). |

Sir Christopher Wren's rejected plan for the rebuilding of London. • 'Rebuilding' |

• Table 2: Selected plans of the enclosure of the City of London from Roman to Stuart times.

The table below illustrates the aspirations of the City of London Corporation for 2036.

|

• Blackfriars. |

• Pool of London. |

• Aldgate & Tower |

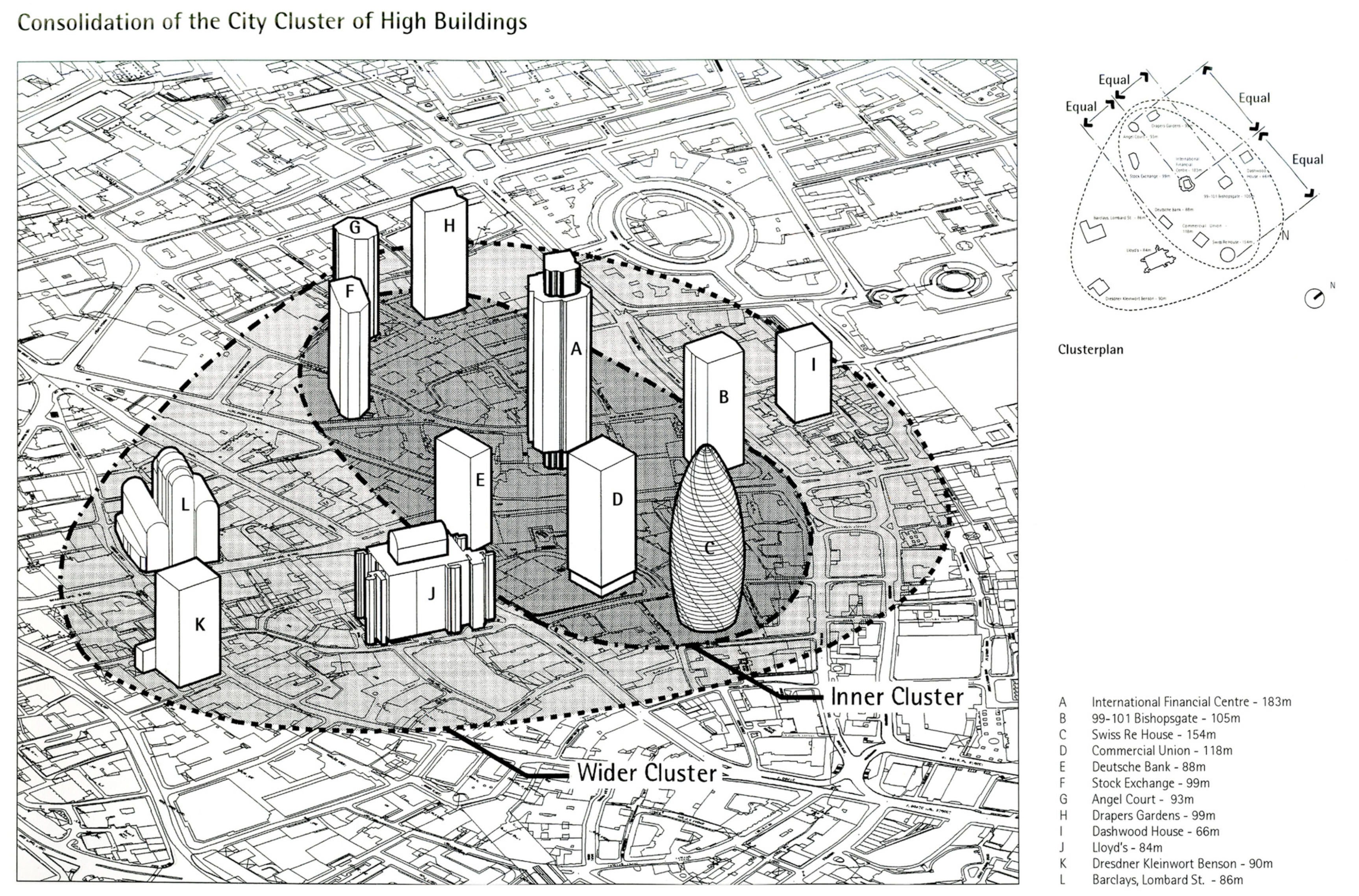

• City Cluster |

|

• Fleet Street |

• Smithfield & Barbican |

• Liverpool Street |

• Key Diagram |

• Table 3: Key Areas for Change in the City of London Plan 2036 - Learn More

Thus this article makes a categorical proposition, namely:—

- ... that the various aspirations of successive power regimes have generated the City of London at the expense of The Commons.

[edit] (2) "How are the 'City of London' and design linked?"

The second point about this article is the categorical proposition:—

- ... that the City of London and design are linked.

According to Abramsom et al., in the introduction to 'Governing by Design: Architecture, Economy, and Politics in the Twentieth Century':—

- "(Arindam Dutta has shown) how design can be entangled within political economy, made to offer up culture in the service of capitalist urban redevelopment, and how such duties govern the professional identities of architects and engineers."

- Daniel Abramson, Arindam Dutta, Timothy Hyde and Jonathan Massey for Aggregate (2012), p.xiv. [6]

In the chapter entitled 'Marginality and Metaengineering', Arindam Dutta has claimed:—

- "... that one of the facets of the commercial extravagance of the recently deceased Gilded Age—the burst of financial speculation from the mid-1990s onward to the implosive doldrums of 2008—was the string of commissions meted out to a roster of “signature” architects with more or less one distinct mandate: to churn out iconic, formally arresting, often sinuous objects whose atypicality would create new points of visual focus for the urban environment. The icons were of a piece with dominant neoliberal ideology. In policy (or lack of thereof ) terms this iconicism relied on two major funding doctrines: the use of sovereign or federal moneys to privilege particular “primary” cities within each nation-state as privileged attractors of global investment; and for “secondary” cities, given the directed retreat of public money for infrastructure support, to use the “cultural” heft from these icons to raise real estate values (and revenue)."

- ib., p.237. [7]

More specifically, in 'Risk Design' (2013), also published by Aggregate, Jonathan Massey has explained the role of Foster + Partners and Arup in the links between the City of London and design. [8]

The article was also published by Archdaily in 2013 as a series entitled 'The Gherkin: How London's Famous Tower Leveraged Risk and Became an Icon' [9], and featured by Archinect in an article by Amelia Taylor-Hochberg entitled 'Investing in risk: How the Gherkin became a British icon' [10].

It is perhaps best summerised in this extract from an interactive illustration by Jonathan Massey & Andrew Weigand:—

- "Known as the Gherkin for its evocative shape, 30 St Mary Axe is the London headquarters designed by Foster + Partners and built in 2004 by reinsurance form Swiss Re. By changing how we imagine the risks of modernization, the building mediated transformations in the economy and governance of the City of London, the self-governing financil district at the heart of the British capital.

- For more than thirty years, the City prohibited skyscrapers in order to preserve its traditional scale, form, and architecture. To build a new tower, developers and architects convinced planning officers that the building would help the City manage threats to its economy and future posed by climate change, terrorism, and the global competition among cities for investment. They did so by designing a building that translated risk into opportunity."

- Aggregate website (2013). [11]

|

• An interactive illustration by Jonathan Massey & Andrew Weigand - click here. |

• Model highlighting the original schema in red, courtesy of Foster + Partners. • Analysis of existing cultural ecosystem, courtesy of City of London. • Frame from 'London Centre for Music' animation by The Mile-Long Opera. Courtesy of Diller Scofidio + Renfro. Diller Scofidio + Renfro's plans for the Centre for Music (CfM) were abandoned in February 2021 and a replacement is planned by the same architects - see below. |

• Table 4: Indicating the architect's role in making design offer up culture in the service of capitalist urban redevelopment.

Thus this article provides an explanation to the way in which the City of London and design are linked.

[edit] Conclusion

The argument fashioned in this article affirms its major premise, namely:—

- ... that the various aspirations of successive power regimes have generated the City of London at the expense of The Commons.

Its minor premise links the City of London and design.

Meanwhile, the dominance of the office building in the City of London continues. Cedric Price wrote:—

- "Defence, energy and commerce have in the past been sufficient generators of cities. This project assumes that education and the need to exchange information may have a similar generative force: cities can be made by learning."

- Cedric Price (1966) 'Potteries Thinkbelt'.

This series of articles concludes:—

- ... that cities can be made by ignorance.

[edit] Notes

[1] Unattributed (2024) 'Commons', Wikipedia.

[2] Unattributed (2024) 'City of London', Wikipedia.

[3] Unattributed (2023) 'Governmentality', Wikipedia.

[4] Barnes, P. (2014) 'A Brief History of How We Lost the Commons: And what we must do to get it back', On the Commons.

[5] American Museum of Natural History' (2023) 'Human Population Through Time (Updated in 2023)', YouTube.

[6] Abramson et al. (2012) 'Governing by Design: Architecture, Economy, and Politics in the Twentieth Century', for Aggregate, available as a download at Academia.

[7] Dutta, A. (2012) 'Marginality and Metaengineering', Chapter 10 in 'Governing by Design: Architecture, Economy, and Politics in the Twentieth Century',

for Aggregate, available as a download at Academia.

[8] Massey, J. (2013) 'Risk Design', Aggregate.

[9] Massey, J. (2013) 'The Gherkin: How London's Famous Tower Leveraged Risk and Became an Icon', ArchDaily.

[10] Taylor-Hochberg, A. (2013) 'Investing in risk: How the Gherkin became a British icon', Archinect.

[11] Massey, J. and Weigand, A (2013) 'Risk Design', Aggregate.

[edit] References

Fellows, N. (2023) 'City Cluster, City of London', Designing Buildings.

Glasman, M. (2014) 'The City of London’s strange history', Financial Times.

Price, C. (1966) 'Potteries Thinkbelt', AD/10/66, p.484.

Price, C. (1969) 'ECHOES', AD/10/69, archived on Google Drive.

Unattributed (2024) 'History of local government in London', Wikipedia.

--Archiblog 10:40, 16 Feb 2024 (BST)

[edit] Further reading

Arup (2024) 'Tall buildings: rising to the net zero challenge', arup.com

Barlow, I. M. (1991) 'Metropolitan government', Internet Archive.

Bollier, D. (2011) 'Ugo Mattei on the Commons, Market and State', bollier.org, 29 July, 11.26 BST.

Bollier, D. (2024) 'David Bollier: news and perspectives on the commons', www.bollier.org

Brandy, K. (2022) 'london plans to demolish two historic buildings for project by diller scofidio + renfro', designboom.

Brown, M. (2014) 'Cultural hub' proposed for London's Square Mile', The Guardian, 26 March.

City of London (2022) 'The City's government', City of London Corporation.

City of London (2024) 'About the City of London Corporation', City of London Corporation.

City of London (2024) 'Research publications', City of London Corporation.

Harvey, D. (2012) 'Rebel cities : from the right to the city to the urban revolution', on the Internet Archive.

McDonnell, J. (2018) 'Big banks must never again be 'master of the economy', The Guardian, 15 September.

Monbiot, G. (2011) 'The medieval, unaccountable Corporation of London is ripe for protest', The Guardian, 31 October.

Monbiot, G. (2011) 'Wealth Destroyers', www.monbiot.com

Monbiot, G. (2015) 'The City’s stranglehold makes Britain look like an oh-so-civilised mafia state', The Guardian, 8 September.

Monbiot, G. (2019) 'Could this local experiment be the start of a national transformation?', The Guardian, 24 January.

Ostrom, E. (1990) 'Governing the Commons', on the Internet Archive.

Sanchez, J. (2021) 'Architecture for the Commons: Participatory Systems in the Age of Platforms', Routledge, London.

Unattributed (2024) 'David Bollier', Wikipedia.

Walljasper, J. (2010) 'All that we share : a field guide to the commons', on the Internet Archive.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

The Shed: Manhattan

Featured articles and news

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Many resources for visitors aswell as new features for members.

Using technology to empower communities

The Community data platform; capturing the DNA of a place and fostering participation, for better design.

Heat pump and wind turbine sound calculations for PDRs

MCS publish updated sound calculation standards for permitted development installations.

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.

Heritage staff wellbeing at work survey.

A five minute introduction.

50th Golden anniversary ECA Edmundson apprentice award

Showcasing the very best electrotechnical and engineering services for half a century.

Welsh government consults on HRBs and reg changes

Seeking feedback on a new regulatory regime and a broad range of issues.

CIOB Client Guide (2nd edition) March 2025

Free download covering statutory dutyholder roles under the Building Safety Act and much more.