Mashrabiya

Shanashil (mashrabiya) are highly decorative enclosed balconies that share a unique relationship with Iraqi society, representing its cultural heritage and the harmony between its artistic and architectural philosophy. They are a part of the Arab culture that stretches all the way back through the history of Islamic architecture.

The name Al-Shanashil has its roots in a non-Arabic word borrowed from the Persian language. The word consists of two parts, Shah meaning king and Shen meaning throne. In some Arab countries, this architectural feature is also called Mashrabiya, however, to maintain the Baghdadi link to these unique features, this article will use the Iraqi term Shanashil.

A distinctive feature of Baghdad’s earliest houses, Shanashil Baghdadiya are among the most well-known of the city’s landmarks and as such they represent one of the most important aspects of the development of Baghdadi civilisation.

Where windows were once used, the development of building techniques - especially in the Al-Abbasi era, when Baghdad was at the height of its civilisation - led to the emergence of the Shanashil (Mashrabiya). At that time, the use of this feature was restricted to palaces and public buildings, however, it was used extensively in the Ottoman era, when it embodied harmony between functionality and beauty, providing a comfortable internal environment in spite of harsh climatic conditions. As Shanashil (Mashrabiya) spread, they appeared in different forms depending on the type of wood and construction techniques used.

Shanashil (Mashrabiya) are usually found on the first floor of a building or above, extending over the street or the inner courtyard of a house. The structure of the Mashrabiya is formed of a series of cylindrical wooden pieces (bars) ranging from 10 cm to 1 m depending on the scale and level of detail of the Mashrabiya.

These bars are spaced at regular and specific distances, with larger pieces - cylindrical or cubic - as points of interconnection between the horizontal bars, together producing precise decorative geometric shapes. The bars are connected to these points using mortise and tenon joints to create a lattice without the need for tools or fasteners such as nails.

Bars are also placed within the framework to distribute loads throughout the lattice, improve stability and prevent the structure from collapsing. Shanashil are usually comprised of two parts: the upper part consists of a tight lattice with delicate narrow bars and the lower part is made up of a more open grid with broad cylindrical wooden bars.

The complex designs of the Shanashil (Mashrabiya) were created by architectural designers and craftsmen who carved wood and inscriptions to produce magnificent decorations and geometric patterns. They also inserted stained glass to add a further aesthetic element to the Shanashil of the old Baghdadi houses.

Given the dry desert climate of the Middle East, high temperatures outside cause high temperatures within the interior spaces of houses, so an architect or artisan designing a Shanashil must consider its orientation and location in relation to the sun’s path. In Iraq in particular, where temperatures reach 55-60°C, the importance of Shanashil lies in their ability to manipulate the interior climate in specific ways.

Firstly, Shanashil help to adjust the temperature inside a house and maintain airflow. The small openings in the Shanashil help a continuous stream of air to flow through the rooms. In the past, the residents of these houses would put earthenware pottery filled with water at the front of the Shanashil so that when hot air entered, the water would evaporate and cooler air would enter the room. Furthermore, Shanashil increase the humidity of the air passing through into the house due to the nature of the material used to manufacture them - a porous material made of organic fibre which absorbs water and maintains the environment.

The second advantage of Shanashil is that they help to control the passage of light. When designing a Mashrabiya, the distances between, and the size of the bars, should be considered. In the upper part, the space between the bars should be narrower to increase light refraction and reduce the intensity of the sunlight passing through, and in the lower part, the distances between the bars should be increased to compensate for the lack of lighting in the lower part.

A further benefit of the Shanashil is that they provide privacy for the residents whilst allowing them to look out over their surroundings. The lower section ensures privacy while the decorative upper part allows air to flow.

Architecturally, Shanashil work to increase the footprint of the rooms on the upper floors, aligning with the ground floor at the right angles to achieve rooms with parallel and perpendicular sides. Shanashil have certainly contributed to the aesthetic of the streets of Baghdad, adding a delicate and picturesque element to the attractive carved wood and decorated façades.

In a more modern context, following urban development, especially in the twentieth century, Shanashil were no longer used in Baghdadi houses and designers created façades of a simpler nature, without ornamentations or decorations.

Given the beauty, practicality and versatility of Shanashil, we will doubtless continue to see new variations of this ancient technique long into the future.

This article was originally published by CIAT in AT issue 122. It was written by Dr Omar Faeq, ACIAT.

--CIAT

[edit] Find out more

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

Art of Building CIOB photographic competition public vote

The last week to vote for a winner until 10 January 2025.

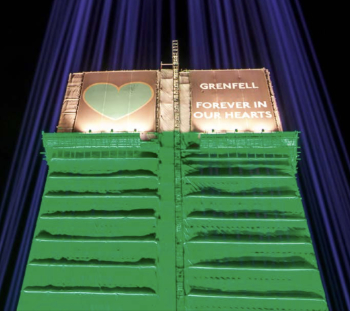

The future of the Grenfell Tower site

Principles, promises, recommendations and a decision expected in February 2025.

20 years of the Chartered Environmentalist

If not now, when?

Journeys in Industrious England

Thomas Baskerville’s expeditions in the 1600s.

Top 25 Building Safety Wiki articles of 2024

Take a look what most people have been reading about.

Life and death at Highgate Cemetery

Balancing burials and tourism.

The 25 most read articles on DB for 2024

Design portion to procurement route and all between.

The act of preservation may sometimes be futile.

Twas the site before Christmas...

A rhyme for the industry and a thankyou to our supporters.

Plumbing and heating systems in schools

New apprentice pay rates coming into effect in the new year

Addressing the impact of recent national minimum wage changes.

EBSSA support for the new industry competence structure

The Engineering and Building Services Skills Authority, in working group 2.

Notes from BSRIA Sustainable Futures briefing

From carbon down to the all important customer: Redefining Retrofit for Net Zero Living.

Principal Designer: A New Opportunity for Architects

ACA launches a Principal Designer Register for architects.

Comments

I have read that the holes in the latticework tend to be larger near the top & smaller near the bottom; the larger holes at the top encourage a draft of the warmer air to quickly escape overhead & cause a slight drop in air pressure, inducing convection air movement indoors. This pressure difference forces air from the street (which is traditionally already cooled by the shape & design of the surrounding buildings & water features) to draw through the smaller holes near the bottom of the latticework, further cooling it through a principle of thermodynamics similar to the Joule-Thomson effect.

Especially in rural areas, people still enhance this effect by placing jars of drinking water near by for passive evaporative cooling which serves a dual purpose of cooling both the air & the water without electricity, and it is speculated that this design was originally inspired from a designated shelf by the window used to hold & cool water using the same principles. I, however, cannot validate any of the above information as I am neither of Middle Eastern origin nor influence.

Thank you for this thought provoking article.