Surveying vernacular roofs

A roof survey should assess its condition, point to explanations for deteriorations and failures, and be alert to any special features or techniques the slater has adopted.

Code of practice for roof slating (CP142) was prepared by the Council for Codes of Practice and published by the BSI in 1942. (Tiling was added in 1951.) It was clear from the start that the members of the drafting committee were aware that it would be impractical for the code’s recommendations to encompass many of the traditional techniques used on existing slate or stone-slate roofs, those we would today class as vernacular. The 1951 edition stated that ‘the code does not deal with stone slating or techniques peculiar to certain parts of the country’.

This difficulty persisted in drafting the next four editions of CP142, its successor BS5534 1978–2018, and BS8000-6 Workmanship on Building Sites: Code of practice for slating and tiling of roofs and claddings 1990–2023. Nonetheless, the committee members tried to include aspects of the more widespread vernacular slating systems. But with innovations in roof design and construction and their consequences, vernacular techniques and materials gradually disappeared from the standards.

Examples of the changes in the standard included: batten sizes increased from 38 x 19mm to 50 x 25mm for all slating, to prevent batten bounce on modern truss roofs, which made it difficult to drive slate nails and resulted in slates breaking; ventilation to cope with insulation at rafter level; and an aversion to the use of mortar and especially lime mortars, resulting in recommendations for mechanical fixing of ridge tiles and, in part, the adoption of plastic dry-verge systems.

Many of these changes are unnecessary for vernacular slating which has been successful in resisting wind and rain over hundreds of years, and they may be incompatible with their details. Unfortunately, the repair or renewal of vernacular roofs often fails to recognise this, and specifications often simply include standard BS clauses or a cut-and-paste from a national building specification. BS5534s scope has recently been revised to draw attention to this. But who reads a standard’s scope? Probably not many.

The code states: ‘This British Standard gives recommendations primarily intended for the design, performance and installation of newbuild pitched roofs, including vertical cladding, and for normal re-roofing work… The recommendations contained in this British Standard might not be appropriate for the re-slating or re-tiling of some old roofs, particularly where traditional and/or reclaimed materials are used. Users intending to adopt any of these recommendations for old roofs, and especially for historically or architecturally important buildings, are advised to consult with the local planning authority or an appropriate conservation organization to check their suitability.’

The gradual changes in the standards reflected technological changes in the slate quarries: the evolution from small and shallow to large, deep quarries. In the former, production was so small that they had to sell a mixture of sizes (random slates sold by weight) mainly to a local market. The large quarries were able to segregate their slates and sell them as single sizes (tally slates sold by count) and, with the development of transport systems, to a wider market. Ultimately, tally slates came to dominate the market as vernacular, random slates gradually fell out of production and the small quarries closed. The consequence for roofs is that vernacular slating is now mainly seen in remote areas and to a large extent on neglected buildings. Happily, the situation for stone-slating was not so bad, and many small delves are still producing, albeit often with long lead times.

To aggravate an unhelpful specification and tendering process, appointed slaters are often unfamiliar with the specific vernacular techniques involved. And all too often the existing roof is stripped without investigating the details of the slating. Consequently, the wrong detailing is adopted for the repair, either by mistake or on the mistaken assumption that the existing detail is unsuitable or defective, and may only need repair for an unrelated reason, such as nails rusting. The consequence is many historic roofs are spoiled or lost every year.

For example, a vernacular valley on a building of high conservation importance could not be installed because the wrong slates had been specified. They were the standard modern production, much larger than the original vernacular slates and too wide to fit to a curved valley. On another roof the wrong valley was installed because the wrong name was used in the specification, despite the slater pointing this out. The Pevsner now describes the valley as beautiful. It may be, but it is wrong, and it should not be where it is.

Look at the roof before pulling it to pieces. Think about what is evident before reslating, and especially before making any changes. It will be money well spent if serious errors are avoided. The objectives of a roof survey are to describe what is there, assess its condition, and point to explanations for deteriorations and failures. It should also be alert to any special features or techniques the slater has adopted.

The oldest slating did not use lead to weather vulnerable junctions or rely on underlay to carry away occasional leaks. Instead, the slater relied on experience and an understanding of how water moves across and between slates and how the flow direction can be influenced. The first level of defence is the lapping between slates, the second is tilt. These are the factors to describe: not simply what is seen now, because the slating may have moved or partially collapsed. Rather, the objective is to understand the original detailing and the slater’s intentions. Besides ensuring that the roof is weather resistant, these determine the roof’s appearance, and are essential for authentic repairs or reslating.

Water penetrates slating unless it is prevented by adequate head, side and shoulder laps. The way the roof has been set out (gauged) may be fundamental to some of the detailing. The slating should be measured to record the slate lengths, the lath or batten gauges, head laps, minimum side lap for each slate length and margins for as many courses as necessary.

There could be as many as 60 courses, so it is easy to get lost between them. The solution is to photograph every course with the slating raked back and including scales. Mistakes can then be checked later, and if the slating has slipped it can be Photoshopped back to its original position. Better still for the most complex details, such as some valleys, is to video the whole process so that the stripping can be viewed repeatedly.

Each part of the roof should be examined in turn. Do the eaves include a wall plate and tilting fillet to raise the slating, or do the rafters foot on to the wall head, with the eaves slating having two short under-eaves slates to make it level and provide tilt? How are verge and top course slates fixed? They may rely on mortar to make them secure, sometimes without pegs or nails. Abutments probably will not include lead soakers or flashing, but is the slating slightly tilted by packing up the laths, or over a raised rafter to direct water away from the vulnerable joint? Is the mortar flaunching protected with listings? How are hips and ridges detailed?

Most of all, any valleys need careful recording, understanding and accurate description. There are many types, some restricted to quite small geographical areas. Recent work in north Wales has revealed four valley types within a 30-mile radius: single cut, shale, Welsh open, and Welsh close-mitred. None relies on lead, and some were devised to cope with the very small and narrow, local slates.

Inevitably, the survey will throw up questions and options for repairs or renewal. Currently the building standards are the main source of guidance but, as explained, they are not ideal. More appropriate guidance is available from the national conservation bodies. Historic England’s Practical Building Conservation: Roofing[1] is excellent on roof detailing, and its Stone Slate Roofing Technical Advice Note[2] (English Heritage) is being revised to include metamorphic slates. A Code of Practice for Slate and Stone Roof Repair and Conservation is in draft. English Heritage’s research on stoneroofing is available as a free download[3]. More generally, The Pattern of Traditional Roofing[4] by Gerald Emerton describes the evolution of slating and tiling.

References

- [1] Historic England (2014) Practical Building Conservation: Roofing, Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, Oxon.

- [2] Historic England (2005) Stone Slate Roofing: Technical Advice Note.

- [3] English Heritage (2003) Stone Roofing.

- [4] Emerton, G. (2018) The Pattern of Traditional Roofing, Glebe House, Acton, Nantwich CW5 8LE

This article originally appeared in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 178, published in December 2023. It was written by Terry Hughes, chair of the Stone Roofing Association and a specialist consultant. He has been a member of the BSI slating and tiling committees since 1983, and was chair of the European slate committee from its inception in 1988 to 2004, and continues as a member.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Aspects of copper roofing.

- Conservation.

- English architectural stylistic periods.

- Heritage.

- Historic England.

- Historic environment.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Planning decision to allow photovoltaic panels on the roof of King's College Chapel.

- The Angel Roofs of East Anglia.

- The iron roof at the Albert Dock.

- The Pattern of Traditional Roofing.

- Vernacular.

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

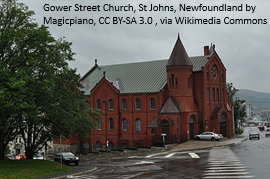

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.