Kerbs

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

As an element of roads and highways, kerbs (kerbstone, crib-stane (Scots) or sometimes curbs (US)) serve a number of purposes:

- Defining the limits of the carriageway.

- Containing the carriageway to prevent 'spreading' and loss of structural integrity.

- Creating a barrier between vehicles and pedestrians.

- Providing a physical 'check' to prevent vehicles leaving the carriageway.

- Allowing surface water to drain away by forming a channel.

Traditionally, natural stone was the most commonly used material for kerbs, but these have now largely been replaced by pre-cast concrete.

[edit] Kerb construction

For most purposes, the top of the kerb should be 100 mm above the road surface. If kerbs are placed too high it can induce ‘kerb shyness’ which is where the width of the carriageway is effectively reduced.

Kerbs are typically laid on a concrete bed of at least 100 mm thickness in such a way that they are joined with the pavement. The back of the kerbing should be haunched with concrete to a thickness of at least 150 mm to provide lateral support. Kerbs can then be tapped down to the correct level. The joints between kerbs are often not mortared but instead they are laid as tight to each other as possible without risking the units spalling.

The basic kerb profiles that are used for road construction are:

- Half-battered.

- Bull-nosed.

- Splayed.

- Square.

Traditionally, most straight kerbs are 915 mm in length but a range of shorter lengths are also manufactured. Radius kerbs are usually 780 mm in length.

Other than those with a square profile, kerbs have a ‘watermark’ or ‘waterline’ above which the surface level and surface water is not normally expected to extend. This generally coincides with a change in angle of the kerb face. It is usual for the surface level to be kept 25 mm or more below the watermark.

Bull-nosed or chamfered kerbs are used to lower the profile of the kerb for pedestrian crossings and driveway access. Linking kerbs between two different profiles are described as transition kerbs or ‘droppers’.

Concrete kerbs can also be cast insitu with an automatic kerbing machine.

A kerb line bend is known as a radius. Sometimes a radius is laid using straight kerbs, although there are specially manufactured kerbs available that can create accurate internal (concave) or external (convex) curves. A radius is described as being either ‘fast’ or ‘slow’, with the fast radius being shorter than the slow one.

[edit] Types of kerb

[edit] Extruded kerbs

Extruded kerb edging is commonly used on long, straight roads such as motorways, dual carriageways and the highways of America and Australia. Using a laying machine, the kerb is formed of concrete or asphalt bonded to the existing asphalt surface.

Extruded concrete kerbs can be laid by a slip-form paver machine that creates the kerb as it progresses along the road.

[edit] Natural stone

Granite is often the most popular choice, although gabbro, basalt and sandstone may also be used. Natural stone has high durability but can be expensive. Highways agencies may experience issues when trying to repair or replace natural stone kerbs that may be over 100 years old as they very often are of random sizes, whereas modern stone kerbs are formed to a standard profile and finish.

[edit] Pre-cast concrete

These are the most common choice for kerbing as they are strong, durable and relatively cheap. In addition, they can be manufactured to strict tolerances.

[edit] Quadrants and angles

Quadrant and angle kerbs are manufactured to complement straight and radius kerbs. They come in a various of different angles and sizes. Quadrant blocks, also known as a ‘cheese’, can be cut to create angles of less than 90°.

[edit] Special kerbs

[edit] Lightweight precast concrete kerbs

Lightweight kerbs are easier to handle, and so there use has been encouraged for health and safety reasons. Kerb lengths are usually 450 mm, and the profile has a frog (recess) which reduces the weight of each unit. Haunch concrete fills the frog so there is no loss of performance when laid.

[edit] High containment kerbs

Also known as trief or titan kerbs, these are bigger than normal kerbs, usually around 450 mm in height and can weigh nearly a quarter of a tonne. Their purpose is to prevent traffic leaving the carriageway and are used on dangerous curves, for pedestrian islands, and to protect footpaths or equipment.

[edit] Bus stop kerbs

These are specially designed kerbs used at bus stops to ease passenger access. They can include a tactile feature such as a rumble strip so that the bus driver is able to assess and minimise the gap between kerb and bus door without risk of making contact with the tyres against the kerb.

[edit] Kerb-drain systems

These are hollowed-out with gaping inlets on the face. Road surface water falls into the internal ‘chamber’ or ‘pipe’ and is directed to the storm water drainage system or a SUDS facility.

[edit] Aesthetic kerbs

These are kerbs that are designed for aesthetic and decorative purposes. For example, they can be textured or feature exposed aggregate.

[edit] Block paving kerbs

These ‘small unit’ kerbs are manufactured to conform with the scale and aesthetics of block paving schemes. As well as being popular on private driveways and courtyards, they are commonly found on cul-de-sacs and feeder roads on residential estates.

[edit] Dropper / dropped kerb

The second edition of The Dictionary of Urbanism by Rob Cowan, published in 2020, defines a dropped kerb/curb (UK/US): ‘A short stretch of kerb that has been lowered to allow vehicles to drive across the pavement and park in driveways which used to be front gardens; a section of kerb lowered to let people in wheelchairs or with buggies to cross the road.’

A dropper kerb/curb is: ‘The kerbstones required to create a dropped kerb.’

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Bituminous mixing and laying plant.

- Coal holes, pavement lights, kerbs and utilities and wood-block paving.

- Cul-de-sac.

- Frog.

- Glass block flooring.

- Ground conditions.

- Groundwater control in urban areas.

- Hazard warning surfaces.

- Highway drainage.

- Infrastructure.

- Landscape design.

- Overview of the road development process.

- Pavegen.

- Pavement.

- Road construction.

- Road joints.

- Section 184 agreement.

- Successful road kerb trial.

[edit] External references

Featured articles and news

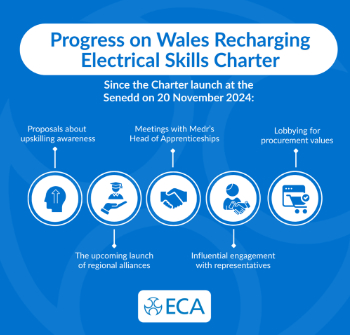

ECA progress on Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter

Working hard to make progress on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.

Many resources for visitors aswell as new features for members.

Using technology to empower communities

The Community data platform; capturing the DNA of a place and fostering participation, for better design.

Heat pump and wind turbine sound calculations for PDRs

MCS publish updated sound calculation standards for permitted development installations.

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.

Comments