Interpersonal Relationships in Auditing

Contents |

Abstract

Auditor training programmes provide solid information around the mechanics of undertaking audits. Generally, they concentrate on the protocols that are to be followed to meet the relevant National and International Standards. Some mention is made of behaviours, but only cursorily.

The psychology of interpersonal transactions underpins the behaviours of both auditors and auditees. This article provides an analysis of transactions that are dependent on the ego-states of the communicators as well as the need to recognise that the paradigm in which the auditor is operating may not be framed in any recognisable way. By understanding this, the auditor is able to conduct the audit in a business-like manner without upsetting the auditee. The auditee will also be able to understand what the auditor is trying to achieve and work towards achieving an amicable outcome.

Introduction

The “OK Auditor”

There has always been a debate, Nature versus Nurture; were you born with a behaviour trait or is it the result of upbringing? It is not the place of this article to solve this argument. The result will leave each person with a distinct set of experiences that can be recalled without thinking as a reaction to a set of circumstances. Harris [2] suggests that neurologically the emotional state at any one time can be stated as being OK or NOT OK. It is natural for a person to consider others to be OK, whilst believing that they are NOT OK. The initial stages of an audit meeting or interview will almost certainly raise feelings of insecurity in the auditee: the auditor may feel the same until the audit is underway.

Part of the skill of the auditor is to assess the emotional status of the auditee and then to allay fears, such that there is an “I’m OK; You’re OK” situation in play. Construction workers, as those in the emergency services and health services, feel that it is not permitted to show weakness. This means that it can require greater skill and emotional insight to audit a Black Hat than a member of office staff.

Transactions in Auditing

Classic Approach

Classically, auditors are told in training courses that there are three forms of behaviour that are common during an audit:

Aggressive: either the auditor or the auditee uses force of character even to the extent of anger to control the other person.

Passive: This is a weak behaviour where one person accepts all suggestions from the other. For example, the auditee may concede a non-conformance where there isn’t one.

Assertive: The auditor presents a business-like approach that respects the auditee. In theory, this makes a great deal of sense until practice shows its weakness. Assertive to a Black Hat is very different to assertive to a junior member of office staff. Until the auditor is experienced, the definition is not easy to comprehend. Explaining just what is meant by the term “assertive” is never easy: this article attempts to provide a useful discourse.

The Transactional Approach

Harris [2] also suggests that there is within each person a Parent, an Adult and a Child. Dependent on the circumstances, the person will exhibit one of these. Gather two together and there will be transactions between them. You only have to stand outside the school gate to hear people talking about one of their kind as though they were a parent. Equally, a bunch of people in a pub having a giggle will be acting as children. Of course, almost all business conversations should be adult to adult transactions.

The human mind subjected to this form of transactional analysis can be shown diagrammatically thus [3]:

This is fine until such time as one person comes in contact with another at which point transaction occurs. The auditor should try as hard as possible to create an adult-to-adult transaction. Issues occur when one or the other changes ego state. This may be the auditor adopting an adult-child approach towards the auditee, for example. This can result in a “crossed-transaction” that will break the transaction or may result in the auditee adopting the child ego state and acquiescing to issues that do not exist. The reader will recognise that there are several other possible transactional scenarios that can be very undesirable for the successful outcome of the audit. The possibilities as shown below [3].

Entering a New Paradigm

The Cultural Web

Scholes and Johnson [4] suggested that any organisation consists of a cultural web composed of a series of elements that together form the paradigm for the way in which it works. The cultural web is shown below:

This paradigm provides the framework in which staff operate on a day-to-day basis. Of course, a member of staff going home or for recreation will enter a different paradigm and will function under a different framework: all of us do this.

Bernstein [1] defines the framework as the “message system” within an organisation, that is how work is organised, sequenced and structured. Whilst his discussion was based on schools and educational systems, his approach can be paralleled in other organisations. For the purposes of this article, the frame of an organisation is based around the formal and informal management system, with which, of course, the auditor should be familiarised as part of preparation. The more difficult aspect to ascertain is the strength of the boundaries within the organisation, especially the informal ones. This is seen in the strictness of adherence to various rules, for example, clocking on and off times may be rigidly enforced in some organisation, whereas a more relaxed approach taken in others. The auditor should look into the more informal management techniques, including the strength of personality and influence held by those in charge.

The Auditor’s Approach

The auditor frequently enters an organisation for the first time. The organisation may be one with which he or she has some familiarity, for example, one scaffolding company will operate to a greater or lesser extent in the same manner as another, at least in terms of conforming to the relevant regulations. Whilst experience of scaffolding companies may be of benefit, each will work to its own paradigm. The auditor must not expect it to work like any other. Of course, moving between disciplines introduces further surprises. The company making isinglass from the swim bladders of fish in India for clarifying beer will operate entirely differently to a microprocessor manufacturer in California. Even within the construction industry many different disciplines exist, especially as more and more technology is incorporated into our projects.

In Conclusion

Auditing is an adventure: the auditor never knows what to expect when entering an organisation. The aim is to examine its operation and report back the findings in an objective manner. To do this, the auditor must take time in research before the audit to learn the paradigm of the organisation – and then not to be rigid about any expectations. Meeting the auditee should be on an adult-to-adult basis with the auditor carefully watching for any potential for crossed-transactions to develop. The assertive approach is defined now as an adult-to-adult transaction that thereby respects both individuals.

So how is the auditor to cope with all this. Above all, and despite any provocation, the auditor must remain calm and business-like. On many occasions, allowing the auditee to express their concerns will defuse the situation. The auditor must be able to recognise the signs where potential conflict may arise. It is important to have concrete evidence that has been agreed and accepted at the place where the evidence was found – but also to carefully assess any further evidence that might arise later, for example, senior management demonstrating without contradiction that the evidence found during the audit was inaccurate.

The auditor should be able to read body language well. It is not the place of this article to go into depth, as many books have been written on the subject. Berne [3] was probably one of the originators of this analysis. However, the body reacts almost without the auditee being aware, which can provide a considerable degree of non-verbal communication. And, of course, the auditor must always be aware of his or her non-verbal communication! The auditor should remember that the first impression that is gained in the first few seconds of a transition will affect the rest of the audit – rumours abound in any organisation, especially when the auditor is there.

It is also important for the auditor to remain wholly independent of the organisation being audited. This can be less easy when auditing one’s own organisation. Independence is shown by not becoming “matey” with the auditee, but without being stiff. Perhaps a family doctor or bank manager provides a useful example. Needless to say, the auditor must never display even a hint of discrimination of any kind.

So, what is there in this for the auditee? The auditee can now understand the approach that the auditor ought to be taking and can prepare carefully for the audit. Hopefully, this will reduce the level of anxiety that is quite normal when a new person enters the organisation. By working with the auditor, the auditee may note improvements that can be made to the paradigm. Whilst the auditor is not empowered to provide consultancy, any issues raised can provide useful direction.

References

[1] Bernstein, Basil, "On the Classification and Framing of Educational Knowledge,"

[2] Thomas Anthony Harris: “I'm OK – You're OK”

[3] Eric Berne: “Games People Play: The Psychology of Human Relationships”

[4] Gerry Johnson and Kevan Scholes: “The Cultural Web”

The original article was written by Keith Hamlyn & reviewed by Kevin Rogers on behalf of the Construction Special Interest (ConSIG) Competency Working Group (CWG). Article peer-reviewed by the CWG and accepted for publication by the ConSIG Steering Committee on 26/1/2022.

--ConSIG CWG 22:09, 29 Jul 2022 (BST)

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Access audit

- Accreditation.

- Audit opinion.

- Certification.

- Design audit

- Energy audit

- Facilities management audit

- First-party audit.

- Internal audit

- Marketing audit

- Pre-demolition audit

- Safety audit

- Self certification.

- Successful Audits - Techniques for Everyone.

- Third party accreditation.

- Third party certification.

Featured articles and news

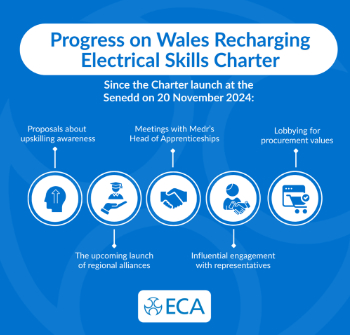

ECA progress on Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter

Working hard to make progress on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.

Many resources for visitors aswell as new features for members.

Using technology to empower communities

The Community data platform; capturing the DNA of a place and fostering participation, for better design.

Heat pump and wind turbine sound calculations for PDRs

MCS publish updated sound calculation standards for permitted development installations.

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.