Howell Killick Partridge and Amis

This article originally appeared as ‘Vertebrate architecture’ in IHBC’s Context 152, published in November 2017. It was written by Peter de Figueiredo, heritage consultant.

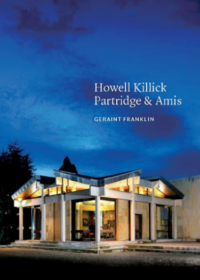

Howell Killick Partridge and Amis, Geraint Franklin, RIBA Publishing, 2017, 218 pages, numerous colour and black & white illustrations, paperback.

After a five-year hiatus, the enterprising series Twentieth Century Architects, produced by Historic England, the Twentieth Century Society and RIBA Publishing, has been revived. Howell Killick Partridge and Amis (HKPA) is the 12th architectural practice to be treated to a monograph, and not before time.

The four architects first worked together at London County Council, where they designed the celebrated Roehampton Lane (Alton West) estate (1955–60). Much influenced by Le Corbusier’s Unités, it was described at the time by the American critic George Kidder Smith as ‘probably the finest low-cost housing development in the world’. Unlike other high-rise schemes of the post-war period it has stood the test of time. On the strength of this project, Howell, Killick, Partridge and Amis left the LCC to set up their own practice, attracting attention for their second-placed entry in the Churchill College, Cambridge, competition, which many felt should have been the winner.

There followed a series of educational projects at Oxford and Cambridge during the 1960s, and at other universities and learning establishments. With these buildings they developed a distinctive style, based on expression of structure and vigorous modeling of surfaces. They pioneered the use of pre-cast concrete, often with exposed aggregate finishes, and exploited the raw texture of timber and other materials. Several of these buildings, including the monumental Hilda Besse Building at St Antony’s College, Oxford, the Acland Burghley School at Tufnell Park, London, and the Mathematics Research Centre Houses at the University of Warwick, are now listed, the latter at Grade II*.

Unlike other architects who could be classified as embracing brutalism, however, they had a sensitive understanding of context, and Geraint Franklin reveals the breadth of their historic sources. In a series of lectures in 1970, Howell explained their theories around ‘vertebrate buildings’ which could be read as a series of structured spaces, and which underpinned the organisation and structural expression of all their work. Howell found prototypes in Celtic beehive tombs, Gothic structural engineering, the Crystal Palace and Buckminster Fuller’s Domes.

After two introductory chapters, the book is divided into sections dealing with different building types. From Roehampton onwards, residential buildings were an abiding interest of the team members, and the sociological concerns of Jane Jacobs became an important influence. The performing arts were a specialist area in which they excelled, the Young Vic and Regent’s Park Theatres being pioneers of flexible planning and elemental design.

The political shift in the 1970s and 80s from spending on higher education to law and order led to HKPA taking commissions for courthouses, prisons and work for the defence sector. The scale of projects changed too, the massive Devonport Dockyard complex, housing nuclear submarines, and Belmarsh Prison being among their most notable achievements. Their most complex vertebrate structure was the Hall of Justice, Trinidad, a tough but elegant solution to the tortuous problems of planning criminal courts, which was completed in 1985.

When establishing the practice, the partners thought that they would all retire on the same day, but the early deaths of Killick in 1971 from multiple sclerosis, and Howell in a car accident in 1974, had a profound effect. Amis retired in 1989, and Partridge, who was never comfortable with the values of the Thatcher era, finally wound up the practice in 1995. The book is illustrated with archive photos, plans and striking new images by the Historic England photographer James O Davies, and comes with a set of post cards and a fold-out strip featuring eight staircases designed by HKPA. Franklin’s incisive and sympathetic analysis of one of the most important architectural practices of the 20th century has been worth waiting for.

This article originally appeared as ‘Vertebrate architecture’ in IHBC’s Context 152, published in November 2017. It was written by Peter de Figueiredo, heritage consultant.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Find out more

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

IHBC NewsBlog

IHBC Context 183 Wellbeing and Heritage published

The issue explores issues at the intersection of heritage and wellbeing.

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.

National Audit Office (NAO) says Government building maintenance backlog is at least £49 billion

The public spending watchdog will need to consider the best way to manage its assets to bring property condition to a satisfactory level.