Contractor’s basis for rating valuation

Contents |

[edit] Use

This method should be used only in the absence of rental evidence and where it is possible to estimate the cost of rebuilding of the hereditament. It is sometimes also used as a method of last resort where the profits method should be used but no reliable accounts are available.

It may be used on such properties as oil refineries, chemical works and cement works, all of which are rarely let, and for which the profits method is inapplicable. It may also be used on many properties occupied by local authorities that are not comparable with other property, and are not let, being owned by the authorities, and therefore cannot be valued by the rental method. Most of these occupations are unprofitable, so that the profits test cannot be applied.

This principle was upheld in Eastbourne BC v Allen (VO) 2001 and Wealden DC v Allen (VO) (2001), in which two local authority leisure centres were under consideration. The ratepayers wanted a profits test to be applied. However, receipts from customers were insufficient for the leisure centres to operate commercially, and the local authorities subsidised them both. The Lands Tribunal held that the profits method could not be applied. In this scenario the total income for the leisure centre would always be equal to the total outgoings, so that the local authority could ensure that the centre continued operating. The profits method, which is based on income, would therefore give a false picture. The Lands Tribunal instead applied the contractor’s test.

Such properties as town halls, sewage works, public conveniences, public libraries and swimming baths must therefore be valued on the contractor’s basis.

[edit] Principles

The contractor’s method relies on the theory that the hypothetical tenant might consider erecting a suitable alternative building for their own purposes if there is none to rent, or if they feel the landlord is asking an excessive rent for their present premises. It is assumed that the tenant would charge themselves a ‘rent’ based upon a percentage of the cost (including land and rateable plant) of the property. The valuer is required to find what has been termed the ‘effective capital value’ of a suitable alternative site and equivalent buildings.

In Eastbourne BC and Wealden DC v Allen (VO) (2001), the Lands Tribunal explained the concept of the contractor’s test:

‘Rateable value is established through the assumption of a hypothetical tenancy; and the contractor’s basis is founded on a further hypothetical assumption - that the tenant has an alternative to leasing the hereditament because they can build similar premises; so that in the hypothetical transaction they would not pay more in rent, and might well pay somewhat less, than the interest charged or foregone on the capital sum employed in providing the “tenant’s alternative”.’

For the purposes of a rating valuation using the contractor’s basis, it is assumed that the hypothetical tenant has contracted for the hereditament to be ready for occupation, complete and fitted out with all rateable plant installed as at the AVD. Costs and values are therefore to be calculated at the AVD.

[edit] Determination of effective capital value (ECV)

To determine the ECV of the site it is necessary to estimate the current cost of providing a bare site suitable for the erection of the building in question, assuming that no other use of that site can be contemplated. The ECV of a site may also be reduced if old buildings are on site so that the full potential may not be realised. The percentage may be related to that used on the buildings.

The ECV of the building is based on either the cost either of reconstruction or of constructing a ‘simple substitute’ building (sometimes called a ‘modern substitute’). In the case of a new building erected to the occupier’s requirements, the ECV is likely to be the actual cost of construction. In the case of an old building, the cost of reconstruction must be reduced to take account of the difference in value between a newly constructed building and the actual building.

Where it is difficult or impossible to envisage the reconstruction of the existing building in its present form, the cost of providing a simple modern building, capable of performing the functions of the actual building, is taken. This figure will be reduced to take account of the difference between the substitute building and the actual building. In Hoare (VO) v National Trust (1998), reiterated in the Wealden and Eastbourne v Allen (2001) cases, it was held that, when valuing a hereditament, it is necessary ‘to adhere to reality subject only to giving full effect to the statutory hypothesis’.

The actual cost of the simple substitute hereditament, less the depreciation for obsolescence of the actual premises, produces the ‘effective capital value’. This may be thought of as the price which the hypothetical tenant would be prepared to pay for the hereditament if they were buying instead of renting it.

[edit] Rate percent on effective capital value

In the past, the choice of an appropriate decapitalisation rate was the source of much litigation. The general principle which evolved from the courts was that the appropriate rate should be related to the rate at which the occupier (or occupiers of a similar type) could borrow capital to finance their outlay.

However, the problem of choosing a decapitalisation rate has been solved. The rate was prescribed by the Non-Domestic Rating (Miscellaneous Provisions) (No 2) Regulations 1989 para.2 for the 1990 rating list. Amendment Regulations in 1994 and 1999 fixed the rates for the 1995 and 2000 rating lists.

The rate is related to the use made of the hereditament, irrespective of the type of occupier. The prescribed rates (all to rateable value) are:

| 1990 list | 1995 and 2000 lists | 2005 list | |

| Educational hereditaments and hospitals (including maternity homes) | 4% | 3.67% | 3.33% |

| All other hereditaments | 6% | 5.5% | 5.0% |

(Note that the decapitalisation rate is a simple application of the percentage, not an application of a yield figure which would be used in a capital valuation. As for all rating methods of valuation, you are looking for a rental value.)

These rates apply also to the valuation by the contractor’s method of rateable plant and machinery within such hereditaments - the Regulations refer to ‘a hereditament the RV of which is being ascertained by reference to the notional cost of constructing or providing it or any part of it'.

With the change to a rate appropriate to use rather than to occupier, it is interesting to note that a particular type of occupier may have different rates applied to different hereditaments. For example, a local authority’s schools are now taken at 3.33 percent, but its sewage works, town hall etc are taken at 5.0 percent.

The various stages to ascertain the rateable value using the contractor’s test can be illustrated by two important cases.

In Imperial College of Science and Technology v J H Ebdon (VO) and Westminster City Council (1984) LT, the situation at the time was that assessments for every university hereditament in England and Wales outside the old London County Council area had been accepted and agreed. All were on the basis of a 3½ percent decapitalisation rate to gross value.

The case was agreed by all parties as a suitable test case for the University of London’s properties, since the approach to the valuations had been different in London compared with the provinces, where the approach was without prejudice to any decapitalisation rate applied.

The two main points of contention were:

- the appropriate decapitalisation rate to be used;

- the scale of age and obsolescence allowance to be deducted from the estimated replacement cost of individual buildings.

In addition, two further points were in debate:

- the propriety of using a deduction to depreciate site value;

- the end allowance, if any, to be used for occupational disadvantages.

The Tribunal accepted the College’s approach in calculating the decapitalisation rate, and referred to the fact that other universities had been valued on a 3½ percent basis. (The rate would now, of course, be 3.67 percent to RV as prescribed by the 1994 Regulations.)

A rate of 11 percent was used for depreciation on both buildings and land. Normally land is not subject to depreciation allowance in the contractor’s method of valuation, but in this case an allowance was given, since obsolescence of buildings was deemed to give rise to a depreciation in land value. This followed rebus sic stantibus which prevents the assumption of the use of land for another purpose.

The Tribunal’s approach was to base its decision on the stages in Gilmore (VO) v Baker-Carr and Others (1983), but to add a further stage and consider the relative bargaining position of the parties in determining the rent. Moreover, ‘effective capital value’ was a long-established misnomer and should be replaced by the term ‘adjusted replacement cost’.

The five stages in the Gilmore case were as follows:

- Estimate construction cost, preferably the modern substitute cost.

- Make the necessary deductions for age and obsolescence etc to arrive at the Effective Capital Value.

- Estimate the cost of the land, rebus sic stantibus.

- Apply the market rate for decapitalisation (now fixed by Regulations).

- Consider any remaining items in valuing the land and buildings such as poor site access and the inflexibility of a district heating scheme (Imperial College Case) - ie those items which would affect rental value rather than capital value.

The Imperial College Case also considered a sixth stage:

- Examine the relative bargaining strength of the hypothetical landlord and tenant and determine the effect on the result of the fifth stage.

The City of Westminster appealed against the decision (1986) but was unsuccessful.

The Eastbourne and Wealden v Allen (VO) cases also confirmed the five-stage method:

- Construction cost of a simple substitute building.

- Deduct an allowance for age and obsolescence, giving the effective capital value.

- Add the land value, for the use of the hereditament.

- Apply the statutory decapitalisation rate to reach the annual value.

- Adjust for factors which might be in the minds of the hypothetical landlord and hypothetical tenant, affecting the rental bid the hypothetical tenant might make, so that the rateable value in terms of the hypothesis is found.

[edit] Example 4

Value for the 2005 rating list the local civic hall. It stands on a site just off the main shopping street, with a frontage of 65m and a depth of 100m. The building has a total floor area of 4000m². At the rear of the building is a car-park for 40 cars. The building was erected in 1935. Although adequate for its purpose, it does not provide the facilities that would be expected in a new building.

Site values and building costs will be based on 2003 figures.

| £ | £ | |

| ECV of site and improvements: Say, net | 100,000 | 100,000* |

| ECV of buildings: 4000 m² at £215 per m² | 860,000 | |

|

Less age and obsolescence Say 27% |

232,200 |

627,800 727,800 |

| @ 5.0% (ie 727,800 × 0.050) | 36,390 | |

| RV | say | £36,400 |

Notes:

- Site value may need to be reduced to reflect less than full potential realised in view of age and obsolescence of actual development.

- Replacement costs of buildings would be based on 2003 prices.

- The figures in these examples have been chosen purely for illustration purposes.

This article was created by --University College of Estate Management (UCEM) 17:08, 6 December 2012 (UTC)

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

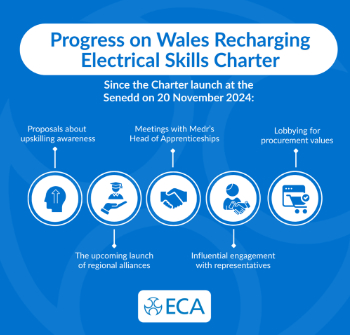

ECA progress on Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter

Working hard to make progress on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.

Many resources for visitors aswell as new features for members.

Using technology to empower communities

The Community data platform; capturing the DNA of a place and fostering participation, for better design.

Heat pump and wind turbine sound calculations for PDRs

MCS publish updated sound calculation standards for permitted development installations.

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.