Commonwealth Heritage Forum

In March 2020 the Commonwealth Heritage Forum was launched at Australia House in London to help countries and communities fighting to save Commonwealth heritage at risk.

|

|

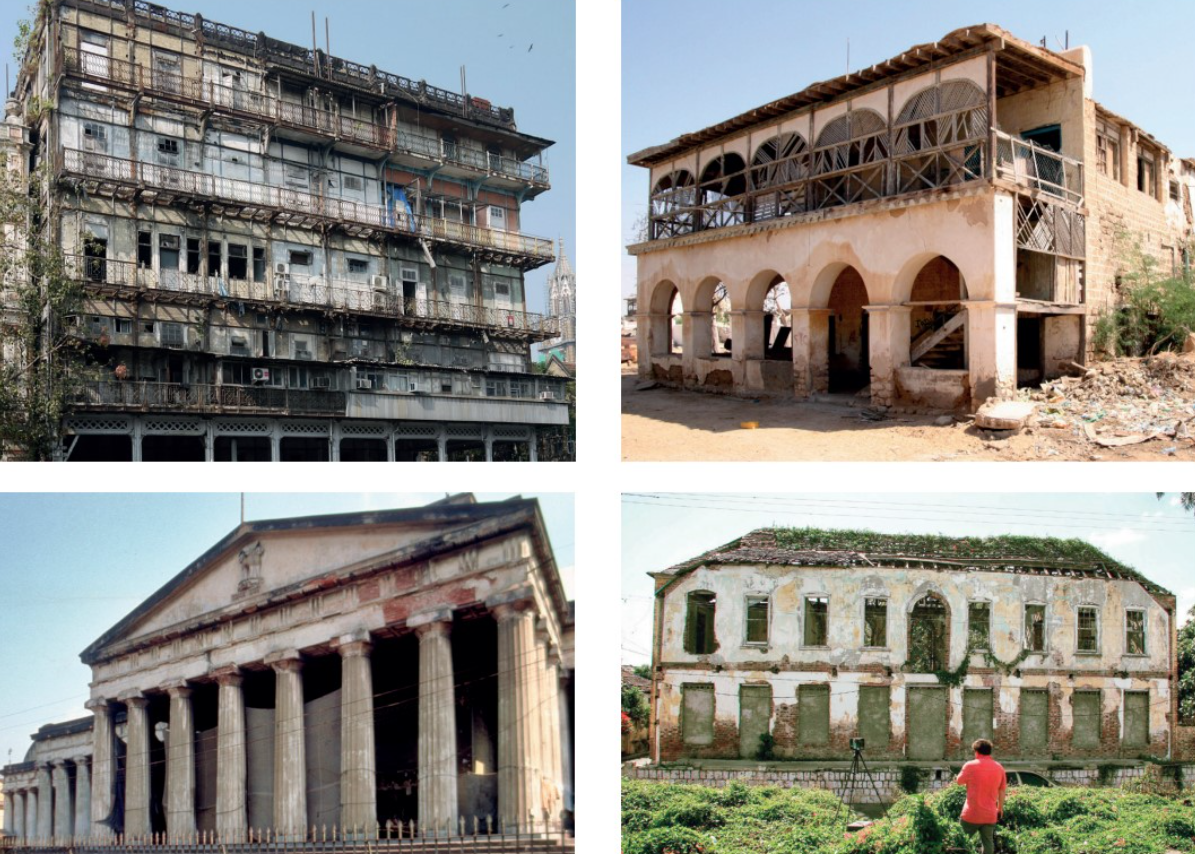

Watson’s Hotel, Mumbai, is the world’s first multistorey, habitable, iron-framed building. Designed by RM Ordish and completed in 1871, it lies severely neglected at the heart of a world heritage site. The former British Residency, Berbera, Somaliland. The Commonwealth Heritage Forum includes countries within the wider Anglosphere. The former British Residency was damaged by bombing in the civil war along with much of the town centre of this fine Red Sea trading port. Manchester House, Spanish Town, Jamaica. This outstanding late-18th-century example of Jamaican Georgian vernacular architecture, built in stone and red brick, is acutely at risk. In 2019 part of the facade collapsed into the street. The Old Silver Mint, Kolkata. One of the finest neoclassical buildings in India, designed by Major William Nairn Forbes in the 1820s and modelled on the Temple of Minerva in Athens, it has lain semi-derelict for decades. |

Contents |

Introduction

The Commonwealth embraces a third of mankind across 54 countries, with a unique shared history and built heritage. Until now there has been no focus for celebrating or promoting this, or for passing on an understanding of its remarkable shared legacy to future generations. Yet over 60 per cent of its peoples are under the age of 30.

All over the Commonwealth, and more widely, from Asia to Africa and from Australasia to the Americas, and even down into the Antarctic, lies some of the most important historic architecture and engineering of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries: public buildings, ports, warehouses, railway stations, bridges, churches, houses, offices, farms, industrial structures, burial grounds, botanic gardens, monuments and memorials – united only in its sheer diversity. These represent a unique global heritage of immense significance, yet it is little researched, little understood, and all too often disregarded.

Although designed by army engineers, local builders, surveyors and architects, they were translated into bricks and mortar by the skills of local people on the ground – not only free artisans, but also the indentured and the enslaved, who introduced their own motifs and artistic traditions. It is a shared heritage built by diverse local peoples across the world over many generations.

Cultural traditions

This rich intermingling of cultural traditions was an early phase of globalisation, but it was not at all one-way traffic. It was multi-lateral and hugely influential. India gave the world the bungalow, derived from the bangala, the original vernacular structures of Bengal. The Indo-Saracenic styles of Bombay (Mumbai) and Madras (Chennai) influenced the design of public buildings further east in Kuala Lumpur, for example. On the other side of the world, the plan form and design of residences in the Carolinas were derived from the early houses of Barbados. Masons from Malta took their skills to Corfu and the Ionian islands, a British protectorate until 1864, where they constructed the Palace of St Michael and St George, one of the great palaces of Europe, and a series of fine classical buildings crafted from imported Maltese stone.

These cross-cultural currents also embraced and absorbed wider influences, such as the mingling of Ottoman, Omani and European styles around the Red Sea, the middle east, east Africa and Zanzibar. Across the world, new materials like cast and corrugated iron were deployed in inventive new ways to create innovative architectural forms and structures.

This was a heritage forged in both peace and in war. Consider the beautiful cemeteries of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, or the spectacular war memorials in Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Wellington, New Delhi, Durban, Ottawa and elsewhere. They are poignant but proud symbols of nationhood, and superb examples of architecture and sculpture inspired by shared sacrifice.

In many Commonwealth countries this heritage is valued as an inextricable part of their national identity. In Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, India, South Africa and Zanzibar, for instance, historic buildings have been adapted with skill and sensitivity for exciting new uses to meet 21st-century requirements. Elsewhere, however, the heritage is acutely at risk from a multitude of threats – climate change, fire, earthquake and cyclone damage, redundancy, neglect, shifting economic and social patterns, political prejudice and, all too often, poor development coupled with a chronic failure to appreciate good architecture.

Some of the biggest threats are faced by small island states with limited access to specialist skills and expertise. In Roseau, Dominica, one of the most important historic buildings on the island, the house of the famous novelist Jean Rhys, has just been demolished after hurricane damage. In Castries in neighbouring St Lucia, a fine early prison building has been levelled by the government in the face of staunch opposition from the St Lucia National Trust. In Grenada the former government house lies in ruins, while in Jamaica fine 18th-century houses, such as Manchester House, Spanish Town, are acutely at risk.

Demolition threat

In Cape Town, some of the most important historic buildings in the town centre have been occupied by squatters. In Mumbai, after decades of neglect and multi-occupation, the old Watson’s Hotel, the first multi-storey habitable iron-framed building in the world, at the heart of the world heritage site, remains threatened with demolition in the face of intense local and international opposition. In New Delhi, architects have been appointed to prepare highly controversial plans for the development of Rajpath, Lutyens’ magnificent ceremonial axis leading to the magisterial Rashtrapati Bhavan, one of the world’s great planned compositions. Bangladesh and Calcutta (Kolkata) have just been ravaged by Cyclone Amphan, causing extensive damage to their historic sites.

The Commonwealth Heritage Forum (CHF) is a broad, inclusive organisation. It welcomes membership from those countries in the wider anglosphere which enjoy a common shared heritage, such as Myanmar, Sudan, Chile, Somaliland, Argentina and Hong Kong, and from UK overseas territories.

In St Helena, a recent survey by the British Napoleonic Bicentenary Trust, supported by the CHF, has highlighted that some of its most important fortifications are falling into the sea from neglect at the very moment when the island has been opening up to tourism. In Bermuda, a rare group of listed workers’ houses within the historic dockyard is endangered for no good reason.

By working together internationally, we can encourage a collective understanding of these threats and share potential solutions. Across the Commonwealth we can all help each other foster conservation-led regeneration, enhance traditional skills, build opportunities for learning, and create jobs and prosperity for all.

Pilot projects

The CHF has four main objectives. The first is to help local organisations and communities prepare registers of Commonwealth heritage at risk, and to support communities fighting to save vulnerable historic buildings and places. To achieve this, we are working closely with Oxford Brookes University and Texas A&M University to harvest the data and deliver the programme. We plan pilot projects in three Commonwealth countries, starting with Barbados. This will involve working with local heritage bodies to train young people and volunteers in specialist techniques and survey skills. In turn, this will bolster local skills and employment, and enhance local capacity and resilience.

The second objective is to support Commonwealth communities as they face the common challenges of rapid urbanisation, climate change and sustainability requirements. Reusing historic buildings and the embodied energy they contain is a crucial aspect of sustainable development. Experience of how to do this needs to be shared. We can all learn from each other and become better stewards of our shared common inheritance.

Third, by creating a digital hub linking members, we can provide access to best practice, advice and professional expertise for those places most in need. With help from our international advisory committee, we are setting up regional chapters in member countries to rapidly grow an inclusive international network. Finally, we are advancing research, education and scholarship in the architectural and engineering heritage of the Commonwealth and its man-made landscapes.

Britain’s heritage does not end at Dover. The UK is a world leader in the breadth and depth of its conservation skills and expertise. However, our architectural perspective remains narrow and anglo-centric, blind to the wider legacy across the world. The time has come to lift our eyes to the wider horizons. The heritage sector has a crucial role to play both in the Commonwealth and as part of the UK government’s commitment to a resurgent global Britain.

The Commonwealth Charter resolves to share experience through practical cooperation. This is exactly what the CHF is now doing, but to continue we need your help and support. We need sponsors inspired by our mission to provide funds, so we can build our capacity to help the most disadvantaged communities.

Follow us on Instagram. Post your own images, and comment on the buildings and places that you value in the Commonwealth. Visit our website and sign up for our regular newsletters. We welcome members who can help by volunteering to support our various committees. Above all, if you care about the shared heritage of the Commonwealth and our heritage at risk programme, please join us as an individual, institution or corporate member. Membership is free for those under 25.

Inscribed on the Commonwealth Gates at Hyde Park Corner are the words of the great Nigerian poet, Ben Okri: ‘Press forward the human genius… our future is greater than our past.’ With your help, support and commitment, we can make it so.

This article originally appeared as ‘Saving the Commonwealth’s heritage’ in Context 165, published by The Institute of Historic Building Conservation in August 2020. It was written by Philip Davies, chair of the Commonwealth Heritage Forum, http://www.commonwealthheritage.org

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

IHBC NewsBlog

IHBC Context 183 Wellbeing and Heritage published

The issue explores issues at the intersection of heritage and wellbeing.

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.

National Audit Office (NAO) says Government building maintenance backlog is at least £49 billion

The public spending watchdog will need to consider the best way to manage its assets to bring property condition to a satisfactory level.