Aspect Contracts (Asbestos) v Higgins Construction 2015

The decision of the UK Supreme Court in Aspect Contracts (Asbestos) v Higgins Construction [2015] UKSC 38 might provide a good reason for adjudication losers who paid up on an adjudication determination in late 2009, or where it is coming up for 6 years since a payment was made pursuant to an adjudication determination, to think about dusting off their files.

All around the world, adjudication is intended as a ‘pay now, argue later’ scheme. If the adjudicator finds for a claimant, then the respondent has to pay up, but without prejudice to the respondent’s right to reclaim that amount in subsequent litigation or arbitration. But what is the basis of that right to reclaim?

During the currency of most formal building contracts, there is a contractual answer to be found in the final account provisions. After the contract work has been completed, these final account provisions typically require a calculation to be made of the amount eventually due under the contract. All the amounts that have been paid up to that point are taken into account, and the balance is paid – or repaid – as the case may be. If the contractor has been paid more than they are entitled to, then the express terms of the contract provide a route whereby the principal gets the excess back.

In the absence of a final account provision, the right of the principal to recover any overpayment is much more problematic. There are certain circumstances where the principal might have a right of recovery in restitution, i.e. for money had and received, particularly where the money has been paid pursuant to a relevant mistake. It might be possible, for example, for the principal to demonstrate a relevant mistake if the contractor has defrauded them by misrepresenting the work that they have done. More rarely, the principal might be able to demonstrate that they have paid as a result of duress; again, that duress would enliven a right of recovery in restitution. In the even more improbable case that the contractor has done no work at all, the right of recovery would be enlivened by a total failure of consideration. These categories are conveniently summarised at Vol 88 Para 405 of Halsbury’s Laws of England:

| Money had and received: An action for money had and received is an action used by claimants who are, for example, seeking to recover from the defendant money which has been paid to the defendant: (1) by mistake; (2) upon a consideration which has totally failed; (3) as a result of imposition, extortion or oppression; or (4) as the result of an undue advantage which has been taken of the claimant’s situation, contrary to the laws made for the protection of persons under those circumstances. |

What about adjudication? If money has been paid pursuant to an adjudicator’s determination, can the respondent principal recover the money that they have paid in restitution?

This was the issue under consideration in Aspect v Higgins. As in so many of these cases, the issue arose not between principal and head contractor, but between head contractor (Aspect) and subcontractor (Higgins). In 2009, after a fairly lengthy period of negotiation and mediation which failed to achieve a result, Higgins obtained an adjudication determination for £490,627 plus interest and fees, which was somewhat more than half of the amount that Higgins had been claiming. Evidently content to leave it at that, Higgins did not issue proceedings claiming the balance of the amount that it claimed.

Instead, in 2012, Aspect issued proceedings seeking recovery of the amount that it had paid pursuant to the 2009 adjudication. It hedged its bets, making its claim both on the basis of an implied term, alternatively restitution. The implied term that it sought was as follows:

| in the event that a dispute between the parties was referred to adjudication pursuant to the Scheme and one party paid money to the other in compliance with the adjudicator’s decision made pursuant to the Scheme, that party remained entitled to have the decision finally determined by legal proceedings and, if or to the extent that the dispute was finally determined in its favour, to have that money repaid to it. |

At first instance, Akenhead J found that there was no such implied term. He said that Aspect could have applied for a declaration as to what the true entitlement was under the subcontract, and if this declaration had been granted in its favour, the court would have had an ancillary and consequential power to order repayment, but it was too late for that because such a claim would have been statute barred. He also found that in the absence of any mistake, duress etc. could be no claim in restitution.

Note that the conclusion in respect of restitution was not in line with the approach in Australia.

Aspect successfully appealed to the Court of Appeal, which found that there was such a term to be implied by the adjudication legislation into the contract. Perhaps pessimistic of its prospects, Aspect did not pursue its appeal in respect of the finding that there was no right to restitution.

Higgins appealed to the Supreme Court, which found not only that there is indeed such an implied term, but also that there is a right to recovery in restitution. This finding has important notifications, both in terms of interest and in setting up a ‘one-way throw’. But first, the basis of the decision.

The court’s starting point was that there plainly had to be a right of recovery of an excessive adjudication determination, because otherwise the legislation makes no sense. It considered first whether an action for a declaration provided a sufficient route for recovery. It said that there was no doubt that Aspect could have sought a declaration, but on the basis of the majority judgments in Guaranty Trust Company of New York v Hannay [1915] 2K be 536, the courts’ power to grant consequential relief as an ancillary to such a declaration was dependent upon their being a cause of action to support that consequential relief.

So where was the cause of action? The court’s answer was that it lay both in implied term and in restitution:

| I emphasise that, on whatever basis the right arises, the same restitutionary considerations underlie it. If and to the extent that the basis on which the payment was made falls away as a result of the court’s determination, an overpayment is, retrospectively, established. Either by contractual implication or, if not, then by virtue of an independent restitutionary obligation, repayment must to that extent be required. The suggested implication, on which the preliminary issue focuses, goes to repayment of the sum (over)paid… |

Why did the court deal with the restitution issue, which had not been before the Court of Appeal, if the implied term would have been sufficient to dispose of the matter? The answer, it seems, was interest: there might have been some doubt as to whether interest would have been payable on a bare implied term case, there was no doubt of the courts power to order interest when making an order for restitution:

| …But it seems inconceivable that any such repayment should be made – in a case such as the present, years later – without the payee having also in the meanwhile a potential liability to pay interest at an appropriate rate, to be fixed by the court, if not agreed between the parties. In restitution, there would be no doubt about this potential liability, reflecting the time cost of the payment to the payer and the benefit to the payee: see eg Sempra Metals Ltd v Inland Revenue Commissioners [2007] UKHL 34, [2008] AC 561. Whether by way of further implication or to give effect to an additional restitutionary right existing independently as a matter of law, the court must have power to order the payee to pay appropriate interest in respect of the overpayment. This conclusion follows from the fact that, once it is determined by a court or arbitration tribunal that an adjudicator’s decision involved the payment of more than was actually due in accordance with the parties’ substantive rights, the adjudicator’s decision ceases, retrospectively, to bind. |

This set up what Higgins described as a ‘one-way throw’, because of the limitation position. Aspect had brought its action less than 6 years since the payment had been made, but it was more than 6 years since the contractual events, such that Higgins was statute barred from pursuing the balance of its claim. Higgins said that it was unfair that Aspect should be free to assert the adjudication determination was for too much, and to claim repayment of the excess, without Higgins being able to assert that the adjudication determination was for too little, and to claim the balance.

The Supreme Court said ‘tough’; this consequence followed…

| …from Higgins’s own decision not to commence legal proceedings within six years from April 2004 or early 2005 and so itself to take the risk of not confirming (and to forego the possibility of improving upon) the adjudication award it had received. Adjudication was conceived, as I have stated, as a provisional mechanism, pending a final determination of the dispute. Understandable though it is that Higgins should wish matters to lie as they are following the adjudication decision, Higgins could not ensure that matters would so lie, or therefore that there would be finality, without either pursuing legal or arbitral proceedings to a conclusion or obtaining Aspect’s agreement. |

This result did not mean, of course, that Aspect was automatically entitled to recovery; it still had to demonstrate to the court that the adjudicator’s determination was excessive:

| The Scheme cannot plausibly mean that, by waiting until after the expiry of the limitation period for pursuit of the original contractual or tortious claim by Higgins, Aspect could automatically acquire a right to recover any sum it had paid under the adjudicator’s award, without the court or arbitration tribunal having to consider the substantive merits of the original dispute, to which the adjudicator’s decision was directed, at all. If and so far as the adjudicator correctly evaluated a sum as due between the parties, such sum was both due and settled. |

And for the purpose of that subsequent consideration by the court or arbitration tribunal, Higgins was not to be confined to the material that was before the adjudicator:

| One further point requires stating. In finally determining the dispute between Aspect and Higgins, for the purpose of deciding whether Higgins should repay all or any part of the £658,017 received, the court must be able to look at the whole dispute. Higgins will not be confined to the points which the adjudicator in his or her reasons decided in its favour. It will be able to rely on all Aspects of its claim for £822,482 plus interest. That follows from the fact that the adjudicator’s actual reasoning has no legal or evidential weight. All that matters is that a payment was ordered and made, the justification for which can and must now be determined finally by the court. Similarly, if Aspect’s answer to Higgins’s claim to the £490,627 plus interest ordered to be paid had been not a pure denial of any entitlement, but a true defence based on set-off which the adjudicator had rejected, Aspect could now ask the court to re-consider and determine the justification for that defence on its merits. |

In other words, the effect of Aspect waiting until the original contract limitation period had expired before seeking repayment was that Higgins could argue the whole of its case, but only for the purpose of disposing of the repayment claim, and if the court or arbitrator eventually found that the adjudication determination was for too little, there would be no scope for a top up.

So the moral is that, for a party who has paid up on an unwelcome adjudication decision, a good time to seek repayment might well be after the contract limitation period has expired, but within the limitation period of 6 years from the payment under the adjudication.

Coincidentally, it was only a couple of days after the judgment in Aspect v Higgins that the Supreme Court of Queensland considered the restitution issue in Gambaro v Rohrig [2015] QSC 170 (19 June 2015). The argument in that case had, of course, taken place before the Aspect v Higgins decision, and in any event, Atkinson’s J finding that there is a right of restitution in these circumstances was founded on the express wording of the East Coast model legislation (which expressly provides for a statutory right to restitution in subsequent litigation or arbitration), and the authority of Falgat Constructions Pty Ltd v Equity Australia Corporation Pty Ltd [1], in which Handley JA held in relation to s 32 of the Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 1999 (NSW) that:

| A builder can pursue a claim in the courts although it was rejected by the adjudicator and the proprietor may challenge the builder’s right to the amount awarded by the adjudicator and obtain restitution of any amount it has overpaid. [2] |

It might accordingly have looked like a foregone conclusion that the court would decline to strike out the principal’s claim for repayment. But it had to consider the basis of Rohrig’s attack, which was that the claim for restitution was premature, since the principal had not waited until the completion of the construction contract, but had launched the proceedings for restitution more or less straightaway after they had paid the adjudicator’s determination. Rohrig relied on the ‘no contracting out’ provisions of the legislation in support of its argument that the contractual regime for interim payments had to yield to the statutory rights to interim payment during the currency of the contract. But Atkinson J was having none of this, finding that the principal was entitled to make their claim for repayment straightaway.

And also, following the same approach as Aspect v Higgins, the court refused to give summary judgment; they would have to prove that the adjudicator’s determination was excessive the hard way.

This is not to say, however, that the Australian position is precisely the same as the position in the United Kingdom. The UK position, as under the West Coast model in Australia, is that the adjudicator is making a determination of what is due under the contract. Under the East Coast model, in contrast, the legislation sets up a parallel right to a statutory payment which sits alongside the contractual right, and it is by no means clear that these rights are identical. On the contrary, it is clear that in some respects (such as in the instance of the right to set off for defective work) the rights are not identical. And so, in a claim like Gambaro, where the loser is seeking repayment, what is the measure against which the adjudicator’s determination is to be measured? Is it the entitlement under the contract, or is it the statutory right to payment? The courts have spoken more than once about the unsatisfactory position which obtains if and to the extent that these rights are out of step, but that observation does not of itself resolve the question.

Let’s look at the relevant section. Since I live in South Australia, I will give section 32 of the Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 2009 (SA):

|

32—Effect of Part on civil proceedings (1) Subject to section 33[3], nothing in this Part affects any right that a party to a construction contract—

(2) Nothing done under or for the purposes of this Part affects any civil proceedings arising under a construction contract, whether under this Part or otherwise, except as provided by subsection (3). (3) In proceedings before a court or tribunal in relation to a matter arising under a construction contract, the court or tribunal—

|

Note that subsection 3 (b) does not tie the courts hands as to what might be considered appropriate. Presumably, it will be appropriate to order statutory restitution under this subsection whenever any amount paid pursuant to the statutory right to interim payment exceeds the contractual right to payment. Section 3 (a) requires the court or arbitrator to take into account any amounts paid pursuant to an adjudication determination, but that does not really answer the question as to what happens in an Aspect v Higgins situation. Suppose that all the rights under the construction contract itself have become statute barred. What is to stop the principal from making a claim for equitable restitution (not statutory restitution under section 32 (3) (b))? Presumably, the principal will be entitled to their ‘one-way throw’, just as in the Aspect v Higgins case.

Which might be quite good reason why, in Australia as in the UK, quite a good time to challenge an adjudication determination is after the contractual limitation periods have expired, but prior to 6 years from the date of payment of the adjudication determination. Assuming, of course, that the Australian courts would follow Aspect v Higgins in finding that there is an equitable right to restitution for overpayment in the circumstances.

The Gambaro case also provides interesting food for thought for those who have pondered how to effectively circumvent the East Coast model legislation. We know that full frontal attacks do not work; they fall foul of the ‘no contracting out’ provisions. A smarter approach might be to provide for a fast track arbitration procedure whereby determinations of adjudicators might be subject to extremely prompt review. The somewhat bizarre consequence of such an approach would be that, as soon as adjudicators award money in favour of contractors pursuant to the statutory right to interim payment, fast track arbitrators would be awarding repayment of that money pursuant to the contractual regime for interim payment. Would such a scheme offend against the contracting out provisions? Applying Atkinson J’s judgment, it seems not:

|

There has been no attempt to contract out of the provisions of BCIPA[4] by the parties. Rohrig exercised its contractual rights by its progress claims and Gambaro complied with its contractual obligations by paying them as assessed by the superintendent. Rohrig also exercised its statutory right to make a payment claim under BCIPA and to refer the unsatisfied part of that claim to adjudication. Gambaro complied with its statutory duty by paying the adjudicated amount. Once the rights under Parts 2 and 3 have been exercised, BCIPA does not seek to exclude the parties from enforcing their rights by civil litigation… The enforcement of contractual rights by civil litigation may give rise to a requirement on one party under s 100(3)(a) to make an additional payment to that paid under Part 3, or it may give rise to a requirement under s 100(3)(b) for the other party to repay some or all of the payments made under Part 3. There is no other express limitation upon the rights recognised by s 100, nor is there any justification for implying any limitation on the rights so recognised. There is no reason why a purposive[5] rather than a literal reading of s 100 would lead to any different result. The purpose of Part 3 is to provide a quick method for the amount of disputed payment claim being determined and then paid. This ensures cash-flow to the builder.[6] However, it is not intended to exclude the parties’ rights to litigate in a Court to determine their rights inter se, so long as amounts paid under Part 3 are taken into account. Nothing in s 100 or in the objects of BCIPA mandates that this may only happen on completion of the construction contract. The defendant’s argument as to striking out the whole of the plaintiff’s Claim and Statement of Claim must fail. |

So the moral might be that the best time to seek repayment of an amount paid pursuant to an excessive adjudication determination is either very quickly, or very slowly.

This article originally appeared as Now We are Six in August 2015.

It was written by --Robert Fenwick Elliott 09:33, 02 Mar 2016 (BST)

[edit] References

- [1] [2005] NSWCA 49.

- [2] At [21].

- [3] The “no contracting out” section.

- [4] Building and Construction Industry Payments Act 2004 (Qld)

- [5] See Acts Interpretation Act 1954 s 14A; Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority (1998) 194 CLR 355 at [69].

- [6] R J Neller Building Pty Ltd v Ainsworth [2009] 1 Qd R 390 at [40]; Capricorn Quarries Pty Ltd v Inline Communication Construction Pty Ltd [2012] QSC 388 at [41].

Featured articles and news

Scottish parents prioritise construction and apprenticeships

CIOB data released for Scottish Apprenticeship Week shows construction as top potential career path.

From a Green to a White Paper and the proposal of a General Safety Requirement for construction products.

Creativity, conservation and craft at Barley Studio. Book review.

The challenge as PFI agreements come to an end

How construction deals with inherited assets built under long-term contracts.

Skills plan for engineering and building services

Comprehensive industry report highlights persistent skills challenges across the sector.

Choosing the right design team for a D&B Contract

An architect explains the nature and needs of working within this common procurement route.

Statement from the Interim Chief Construction Advisor

Thouria Istephan; Architect and inquiry panel member outlines ongoing work, priorities and next steps.

The 2025 draft NPPF in brief with indicative responses

Local verses National and suitable verses sustainable: Consultation open for just over one week.

Increased vigilance on VAT Domestic Reverse Charge

HMRC bearing down with increasing force on construction consultant says.

Call for greater recognition of professional standards

Chartered bodies representing more than 1.5 million individuals have written to the UK Government.

Cutting carbon, cost and risk in estate management

Lessons from Cardiff Met’s “Halve the Half” initiative.

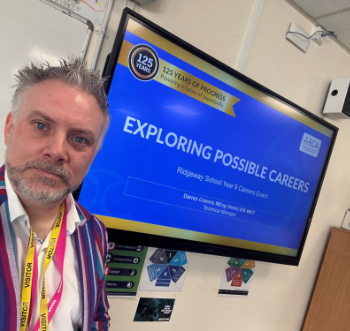

Inspiring the next generation to fulfil an electrified future

Technical Manager at ECA on the importance of engagement between industry and education.

Repairing historic stone and slate roofs

The need for a code of practice and technical advice note.

Environmental compliance; a checklist for 2026

Legislative changes, policy shifts, phased rollouts, and compliance updates to be aware of.