Artificial intelligence and real stupidity

Ill news hath wings and with the wind doth go,/ Comfort’s a cripple and comes ever slow. This heroic couplet comes from Michael Drayton’s dramatic docu-poem The Barrons Warres. The historical context is Edward II’s frustration at being unable to cross the Trent while pursuing the rebel Earl of Lancaster in 1322. The idea was a meme in the 17th century, also cropping up in works by Milton, Dryden and others, but it is really just a spin of the age-old truism Nullum nuntium bonum nuntium – no news is good news.

Perhaps it was to counter this that inspired Robert Browning to write How they Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix, a very well-known poem which appears in all the anthologies that well-meaning great aunts are apt to give children for their ninth birthday. Despite superficial accuracy, the poem is inherently unsatisfactory. What sort of fantasy horse can gallop for 130 miles? And what sort of good news, required to ‘save Aix from her fate’, could need overnight delivery at super-equine speed? Perhaps the poem’s lack of any historical context is telling: good news really is a bad traveller.

By virtue of the internet, we are used to any old idea putting a ‘girdle round about the earth’ in less time than it took Puck to pick a posy of pansies; and doing so before anyone has considered whether it has any connection to reality. Whatever happened to Sophocles’s maxim: quick thoughts are seldom safest?

In the world of cultural heritage we are accustomed to new ideas travelling sedately, like the gradual evolution and spread across Europe of the gothic style and later the renaissance. Even today, the good news that historic buildings can be better conserved with the correct choice of lime mortar has taken the whole of my career to reach partial success, whereas the snazziest ideas in kitchens and bathrooms can be everywhere before the proverbial ink is dry.

We are used to back-projecting the idea of personal transmission of cultural ideas in art through the concept of ‘schools’, in which similarities of philosophy, content and technique are presumed to denote hotbeds of collaborative activity, often with little or no documentary evidence.

Raphael’s School of Athens resides at about Camp 3 on the long trek through the Vatican to the Sistine Chapel. In it we see 58 philosophers hanging out in an elaborate mall, despite having had by-no-means- overlapping lifespans. The identities of most of the figures is hotly contested in academic circles but there is more unanimity as to which are portraits of Raphael’s contemporaries. Recently one figure has been the subject of an internet meme, much to the dismay of serious scholars. The figure in white just left of centre, and the only one looking straight at the camera, is not, after all, the young Francesco Maria I della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, favoured nephew of the work’s patron Pope Julius II. It is proclaimed as the first century Egyptian mathematician Hypatia. At a stroke this transforms Raphael from a notorious male chauvinist to a revolutionary feminist icon.

With proper documentary records, recent art history takes a different course. The After Impressionism exhibition at the National Gallery charts the emergence of modern art from its cradle in post-impressionism through the ever-shifting pattern of artistic groups – nabis, cubists, fauvists and all – with ideas passing gradually from artist to artist in pubs and cafes, in their manifestos and short-lived magazines, and as new works travelled around Europe from exhibition to exhibition. From the exhibition Paul Sérusier’s The Talisman: landscape in the Bois d’Amour of 1888 only now emerges as the first recorded work of the abstract school.

With the world getting ever more frantic, we now have to add artificial intelligence to the mix. Until recently, the best counsel has been to fear real stupidity more than artificial intelligence. But recent chatbot contributions to world art are worrying. They will be designing innovative lime-mortar mixes soon; and jokes: ‘an artist of the abstract school, a fantasy horse and a chatbot go into a pub…’. It will be ill news, and with the wind doth come.

This article originally appeared as ‘Artificial intelligence and real stupidity’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 176, published in June 2023. It was written by James Caird.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

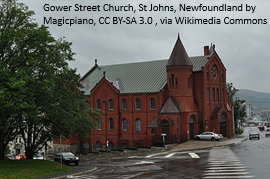

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.