Adaptive structures

On 1st September 2016, Designing Buildings Wiki attended a panel discussion at The Building Centre as part of the Adaptive Structures exhibition.

Designing strength into buildings to prevent collapse has been the underlying tenet of structural engineering since before the ancient Egyptians built the first pyramids. A second fundamental principle, which appears in all modern design codes, is to build structures that are stiff enough to prevent excessive movement and deformation under statistically-calculated worst-case loads, such as high winds, heavy snow, large crowds, and so on. This is not really a question of safety, rather it is about the usability of structures and the comfort of the user, termed ‘serviceability’ requirements.

Adaptive structures are designed by separating the two engineering principles using conventional structural materials for safety (a passive system) and another (active) system to control movements, thereby maintaining comfort and usability.

Ed McCann, director of Expedition Engineering, and Gennaro Senatore of University College London, began by explaining their recent collaboration on adaptive structures, which unlike conventional structures, can successfully change their shape to prevent excessive movement under load. They claimed that super-slender structures could now be created that use much less material, less whole-life energy and achieve very high levels of performance. But the question remains as to whether this is practical in the real world?

Senatore explained how he developed a high performance structure that was capable of counteracting loads actively by means of actuators, sensors and control intelligence. Using these methods, a full-scale prototype was developed, in the form of a very slender space truss with embedded sensors and actuators, which performed successfully as predicted.

He explained that the control system architecture was designed with the primary aim of identifying the response to loading in terms of internal forces and displacements for the structure. This allows the prototype to control itself without user intervention or predetermined knowledge of the external load.

He discussed how the prototype could be adapted to structures such as portal frames, arch bridges, doubly curved vaults, spatial trusses, exoskeleton structures like The Gherkin, and so on.

The prototype structure is a 6,000 mm (length) x 800 mm (width) x 160 mm (depth) cantilevered truss with a 37.5:1 span-to-depth ratio.

This degree of slenderness is not possible with conventional structural solutions (a ratio of 12:1 might be expected for conventional trusses, and 20:1 for conventional steel beams). This could allow for slender structures to be built in limited space, whether due to refurbishment, architectural desire, constraints on height, or limited footprints for tall buildings.

The structure consists of 45 passive steel members and 10 electric linear actuators strategically positioned within diagonal members which are under tension. The structure is designed to support its own (dead load) weight (102kg including actuators and cladding), plus a live load of 100kg at the tip of the cantilever.

The frame is fully instrumented to monitor stress in the passive members, the deflected shape, and the operational energy consumed by the active elements. The passive steel members in the truss have been sized to prevent collapse, but instead of adding more material, a state-of-the-art control system governs the more onerous requirements of deflection and movement. Due to the fail-safe nature of the actuators, if the power is cut, the actuators simply stop moving with no compromise of load carrying capacity.

In order to validate the performance of the prototype, load tests were carried out by placing weights ranging from 10kg to 100kg at the cantilever tip. The operational energy use was measured by monitoring the power being consumed by the actuators and the control hardware during load/displacement control.

The total energy (embodied + operational) of the prototype was then benchmarked against that of two equivalent passive structures. The first structure was made of two steel I-beams; the second was a truss designed using state-of-the-art optimisation methods. The adaptive truss achieved 70% total ‘whole-life’ energy savings compared to the I-beams, and 40% compared to the passive truss.

These experimental results confirmed that the adaptive structures design method, and adaptive structures in general, could save substantial material mass and total energy compared to equivalent passive structures.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Actuator.

- Biaxial bending.

- BREEAM Functional adaptability.

- Bridge construction.

- Cantilever.

- Concept structural design of buildings.

- Concrete-steel composite structures.

- Elements of structure in buildings.

- Exoskeleton.

- Limit state design.

- Long span roof.

- Major cast metal components.

- Mesh mould metal.

- Structural engineer.

- Structural modeling and analysis.

- Structural steelwork.

- The design of temporary structures and wind adjacent to tall buildings.

- Types of structural load.

Featured articles and news

Great British Energy install solar on school and NHS sites

200 schools and 200 NHS sites to get solar systems, as first project of the newly formed government initiative.

600 million for 60,000 more skilled construction workers

Announced by Treasury ahead of the Spring Statement.

The restoration of the novelist’s birthplace in Eastwood.

Life Critical Fire Safety External Wall System LCFS EWS

Breaking down what is meant by this now often used term.

PAC report on the Remediation of Dangerous Cladding

Recommendations on workforce, transparency, support, insurance, funding, fraud and mismanagement.

New towns, expanded settlements and housing delivery

Modular inquiry asks if new towns and expanded settlements are an effective means of delivering housing.

Building Engineering Business Survey Q1 2025

Survey shows growth remains flat as skill shortages and volatile pricing persist.

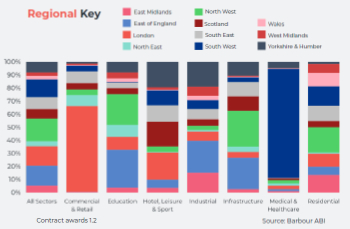

Construction contract awards remain buoyant

Infrastructure up but residential struggles.

Home builders call for suspension of Building Safety Levy

HBF with over 100 home builders write to the Chancellor.

CIOB Apprentice of the Year 2024/2025

CIOB names James Monk a quantity surveyor from Cambridge as the winner.

Warm Homes Plan and existing energy bill support policies

Breaking down what existing policies are and what they do.

Treasury responds to sector submission on Warm Homes

Trade associations call on Government to make good on manifesto pledge for the upgrading of 5 million homes.

A tour through Robotic Installation Systems for Elevators, Innovation Labs, MetaCore and PORT tech.

A dynamic brand built for impact stitched into BSRIA’s building fabric.

BS 9991:2024 and the recently published CLC advisory note

Fire safety in the design, management and use of residential buildings. Code of practice.