Town and Country Planning Act 1968

2018 marked 50 years since the Town and Country Planning Act 1968 was passed, bringing effective protection of listed buildings for the first time. It was the key to the conservation revolution.

|

| Elevation and staircase of 24 High Street, Bath, a listed building demolished in 1964 without fuss. |

Mention of the Town and Country Planning Act 1968 in many circles will prompt mention only of structure plans, action areas and public participation in planning. Yet tucked away in Part V, if you got that far, was a revolution in heritage conservation.

It was the most significant measure of all the acts from the Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882 to the present. True, listed buildings were provided for in the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947, but the protection given to them was slight. True, the Civic Amenities Act 1967 was far-reaching and popular, but conservation areas were more titles than teeth.

Protection prior to 1968 was deficient. Some controls for buildings of special architectural or historic interest came in the Town and Country Planning Act 1932 but the main provisions were in the Town and Country Planning Act 1947. Anyone wishing to demolish a listed building had to give two months notice to the local planning authority. The authority could then either allow the works to proceed or make a building preservation order (BPO). If a BPO were made, the building was not yet safe. The BPO had to be confirmed by the minister. And if it was confirmed, it was then open for application to be made to demolish. Further, if that was refused by the local authority, appeal could be made to the minister. It is not surprising that there was no appeal against the failure to make a BPO.

Under this regime listed buildings could be removed easily. The redevelopment of part of the High Street in Bath, close to the Abbey and opposite the Guildhall, was typical of what was going on in many towns and cities in the 1947–68 period. 24 High Street was listed. It was early 18th century, with a fine staircase, and even a curious stone-panelled room possibly linked to John Wood. The Bath Preservation Trust archives have files on the redevelopment but there is no record of any moves against demolition. Documents relate only to the suitability – height, scale, materials – of the proposed replacement.

The Georgian Group and Royal Fine Art Commission joined in, again focusing on the quality of the new, not the loss of the old. The Trust bemoaned The Sack of Bath, ‘…failed to preserve the west facades of the old High Street where today the hideous sham mansards of painted aluminium and the ill-spaced windows of the Harvey block disgrace the heart of the city’. True, but the council was bent on redevelopment so would never have sought a BPO.

In what for many was the most grievous loss in 1947–68, we know that a BPO was pressed for by campaigners, but none was made. In 1960, the British Transport Commission gave notice of its intention to knock down the listed Euston Arch. The London County Council raised no objection (provided the Arch were re-erected elsewhere). Later an MP asked the minister in Parliament to make a BPO. In reply, the minister felt he was not justified in intervening. This story is related painstakingly, pain implied on every page, in The Euston Arch by Alison and Peter Smithson – modernist architects both, please note. The ‘greatest monument to the passing railway age’ (Pevsner, in his Foreword) was demolished in 1962; and it has not been re-erected, at least not yet.

By 1964 344 BPOs covering 1,233 buildings had been made (with more protected by refusal of planning permission or by planning conditions). That is some 20 a year from 1947. Losses of buildings without a BPO would have been in three figures, to go by later data (see below).

In these and other cases, it was not just the cumbersome procedures that made this system weak. The compensation provisions put off many authorities. The onus rested on the authorities to act and make their case. If the local authority did nothing, silence was taken as acceptance. And the burden of proof by implication was on those who wished to protect, not those who wished to destroy.

Lord Kennet, parliamentary secretary (junior minister) in the Ministry of Housing and Local Government, 1966–70, deserves a place in preservation history for the listed building consent provisions enacted in 1968. He did not publish a diary of his time at MHLG but he did write a book, Preservation, shortly after. There he recounts first the difficulty of getting conservation areas through the ministry. Winning through on Part V of the Town and Country Planning Act 1968 proved even harder.

The fight lasted eight months, Kennet records. Civil servants, whose ‘solicitude for property interests’ surprised him, did not do things they had agreed to do, left out things in papers he had asked for, sent papers to the senior minister (then Anthony Greenwood) that he had vetoed, and even declined outright to put forward what he wanted. The officials calculated, one infers, that they could see off a mere junior minister by going to the top of the MHLG or to the Cabinet committee that had to approve the contents of the forthcoming bill. Yet Kennet won. He puts Yes, Minister in the shade.

It is hard to prove the very idea of listed building consent was Kennet’s, as well as the Whitehall victory. It is interesting, however, that the redoubtable Jane Fawcett, thought by Pevsner to be too fierce, described her ‘despair over the system’ in a private letter to Kennet in 1966 (Box 119, Kennet papers, Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge).

She writes: ‘the cases of buildings covered by BPOs that gradually deteriorate and finally are demolished are numerous’, but does not press the then new minister to do away with BPOs or to introduce something radically different. And Preservation shows Kennet’s grasp of the weaknesses of the 1947 system, and his study of protection in France and Italy; and one may safely assume the idea did not come from officials.

Kennet’s system, if one may put it like that, required application (not notice) to demolish (or alter or extend affecting its character) a listed building. Silence betokened refusal. The onus, at least by implication, was on the applicant to say why demolition was thought necessary. The local authority had to have regard to the desirability of preservation (another 1968 clause) and the ensuing circular was firm on this (passages show every sign of Kennet’s pen, and the National Planning Policy Framework passage is anodyne in comparison).

The term ‘listed building’ was defined for the first time and for the first time really meant something. Local authorities were required to consult the national heritage societies about listed building consent applications involving demolition, a rare statutory obligation in favour of voluntary bodies. There were many related provisions too, especially strengthening measures on compensation and penalties.

The measures are still in force half a century later. They have not been significantly altered; nor has there been significant pressure to weaken, or strengthen, them. This is despite their radical nature and the marked shift they entail from individual property rights to state control.

This last point arose when the bill was before the House of Commons. Sir Derek Walker-Smith MP described the new powers as ‘probably wrong and inequitable… [giving] no appeal or right of representation to an owner whose property is listed… perpetrating an inequity upon those who own them’. Graham Page MP questioned the automatic preservation that was to become inherent in listing: ‘the automatic preservation order will have unfortunate effects’. Yet the bill passed.

Michael Ross sums it up in his ‘Planning and the Heritage: policies and procedures’: ‘The English person’s tendency to cherish their property rights… listed building control can be seen as the heavy hand of the state descending on and restricting those rights in an arbitrary and unfair way. Remarkably few owners have seen it that way. Rather, there has been a pride in ownership.’

The MHLG told Kennet (after initially saying they had no figure) that 400 listed buildings were lost in 1966. The number fell to 266 in 1969, the first full year of the operation of Part V. By 1982 it was 161 and almost 100,000 buildings had been added to the lists in the previous 10 years.

This reduction, absolutely and as a proportion of the listed building stock, would not have occurred without the 1968 act, but it was the pressure of public opinion and the work of heritage bodies that brought it about. We have had a conservation revolution, and it was a politician of unusual calibre, not a heritage campaigner, who was instrumental.

Demolitions are now exceptional. Applications to demolish have fallen below 50 a year and most are refused. Most of the recent campaigns of, for example, SAVE Britain’s Heritage (152-158 Strand; Royal Mail sorting office, Paddington; 66-68 Bell Lane, Spitalfields – all London; and 26 Market Place, March; Hexham Union Workhouse; Wilton Terrace, Cambridge) have concerned unlisted buildings.

Notably, nature conservation has not enjoyed anything as radical. Local planning authorities are expected to have policies to protect Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). Owners and occupiers of SSSIs are required to obtain consent to carry out certain activities like grazing or fishing. But there is no SSSI consent. If a road or housing scheme, say, is proposed, the law demands only that the appropriate conservation body is consulted.

The heritage world, for all its travails, has much to be grateful for.

Reference:

- Kennet, Wayland (1972) Preservation, Temple Smith, London.

This article originally appeared as ‘The revolution that lasted’ in IHBC’s Context 154, published in May 2018. It was written by Timothy Cantell, a planner and writer who worked at the Civic Trust and the RSA, and was a co-founder of SAVE.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Conservation area.

- IHBC articles.

- Listed building.

- Nikolaus Pevsner.

- Planning and Compensation Act 1991.

- Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act.

- Planning legislation.

- Planning permission.

- The Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (Amendment) (England) Order.

- Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012.

- Town and Country Planning Act.

- Town and Country Planning Association TCPA.

- Town planning.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

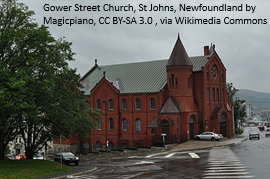

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?