The green belt and historic buildings

This article originally appeared as ‘Green belt: friend or enemy of historic buildings?’ in IHBC's Context 146, published in September 2016. It was written by Carole Fry, a director of AHC Consultants, freelance writer and architectural historian.

Do the 14 green belts in England still fulfil their original aims? How can we meet the demand for new housing without building on green belt? How is green belt affecting the morphology of English towns and cities? Is the green-belt designation creating an unacceptable amount of pressure on our historic towns and cities? Would reducing the nationwide green-belt area relieve pressure in our historic towns (but only create pressure on our rural heritage assets)?

Despite what you might read in the press, none of these questions is new. Many of these concerns were debated almost immediately after the formal designation of the green belts in 1955. Had they overdone it? Were these new, green, buffer zones too wide, and were they preventing the healthy growth and normal development of our urban areas?

As early as 1820 the visionary landscape architect John Claudius Loudon (1783–1843) envisaged cities as concentric rings of buildings interspersed with open green areas. The idea of green belt itself stemmed from the work of Ebenezer Howard (1850-1928), the founder of the garden city movement, and others who followed where he had led. Howard’s advanced ideas influenced the London Society, which was formed in 1912 by those who were keen to advance the practical improvement and artistic development of London.

Early members of the society included Sir Edwin Lutyens, Raymond Unwin, Aston Webb, and other leading architects, politicians, artists, engineers and planners. Based on Howard’s vision, they produced the Development Plan for London of 1919, which called for the provision of green spaces in what were then the outer suburbs. This was green belt in its nascent stage.

In 1935 London County Council (LCC) pursued the idea of a green belt for the capital and in 1938 the Green Belt (London and Home Counties) Act was passed. In order to preserve green spaces in line with this plan, the LCC embarked on a programme of buying up land to create an encircling park around the capital. Intended to be a series of green spaces (not a continuous, circular green park) and to be publicly-owned and accessible, by 1939 the LCC had bought 8,000 hectares of land to this end. Duncan Sandys, the conservative minister for housing, finally implemented the green belt formally in 1955 when he encouraged other towns and cities to do as London had done.

Ever since the establishment of the London green belt (and the 13 others surrounding English metropolises, which include Nottingham, Preston, Liverpool and Cambridge), the value of the designation has been queried. Contrary to the original aims of the London Society, that open spaces for amenity and recreation be available for city dwellers, most of the green belt nationally is in private ownership, not open to the public. Only 13 per cent of London’s extensive green belt is accessible to the public, for example. This creates questions of social justice: does the value of privately-owned green belt really extend beyond the residents who live in it? Or is it a designation which only protects small pockets of the affluent and keeps property prices high by preventing building? And, most important for us, where does the heritage fit into all this?

Tom Papworth of the Adam Smith Institute wrote a controversial article in 2015 which stated that 2.5 million homes would be needed over the next 10 years, all of which could be built on just two per cent of the country’s green belt.[1] Papworth has made some points which we, as heritage practitioners, should be addressing, regardless of our political views. Looking at this issue purely from a heritage perspective, the key point we should be considering is whether retaining the green belt as inviolable is creating a default position of pressure to build in towns and cities, since development cannot go anywhere else. Further, the retention of green belt reduces the amount of green space in urban environments because land is made too valuable to leave undeveloped.

This situation forces development to be squeezed into already over-developed, dense historic town centres, with the inevitable result that the only way is up. Papworth, rather startlingly, advises us to ‘build on green belt or be dominated by skyscrapers’. While we are not quite at this point yet, one has only to look at Canaletto’s famous painting of the Thames, superimposed by the same view today, to see what he is driving at.

In the early years of green belt policy, the breakdown of the cost of housebuilding was very different from today. In the late 1950s land constituted approximately 25 per cent of the overall cost of new housebuilding; today the figure is 70 per cent. Naturally this puts land at a greater premium, especially in town centres where it is scarce. The result of this is that developers want to (and in some cases need to) use every inch of the available space a site can offer. This is having a profound and homogenising effect on architecture and design. Almost without exception modern developments are seeking to maximise the built form on any given site and, as a corollary, to minimise associated amenity space or green areas.

At the same time, for the same reasons, they are seeking to develop vertically rather than horizontally. Denser, higher developments are the result, and these two characteristics are now prevailing in architecture and design. Aside from the rather stifling effect that this is having on architecture, these two characteristics, of higher density and vertical development, can be highly damaging for smaller-scale, lower historic buildings and existing, historic town centres or conservation areas.

Coupled with this is the fact that the population in England has increased by 40 per cent since the early 1950s, creating a much higher pressure for new housing than ever existed when green belts were first brought into existence.

At a recent hearing in Sevenoaks, developers were seeking to erect 18 luxury apartments, over three storeys, within the heart of the historic town, within the conservation area. This was, in my view, a poor scheme, which paid little attention to its historic context. The inspector, rightly, in my view, dismissed the appeal. However, the pressure to build within Sevenoaks, and many other similar towns, is huge and remains a very real threat to the historic environment. The Sevenoaks District is 93 per cent green belt. As it is politically unacceptable for council members to allow building within this designated land, or indeed to reduce or roll back the green belt, the only alternative is to look at the town centre again and again. Winning one significant hearing will not solve Sevenoaks’ problem; the developers or others like them will be back.

As all conservation officers will know, councils across the country are being forced to allocate land for housing to meet the expected demands. For many councils, especially those in green belt, it is proving very hard to find this land, leaving them open to hostile planning applications from developers. Despite this known difficulty, in October 2014 two new paragraphs were written for the Housing and Economic Land Availability section of the Planning Practice Guidance that accompanies paragraphs 14, 83 and 159 of the National Planning Policy Framework (2012). This now makes it clear that green belt boundaries will be altered only in ‘exceptional’ cases. Far from re-examining the usefulness of green belt as a mechanism (and much less considering green belt’s impact on heritage assets), the guidance has simply been tightened.

The positive side of retaining the green belt in this strict manner is that the rural heritage is, in theory, under far less pressure than its urban counterpart. In general, it is difficult, if not impossible, to obtain consent to build in green belt. In many thousands of cases this has had the helpful effect of protecting vulnerable historic buildings and their settings in the countryside. But do we need to accept a one-or-the-other scenario? Is it a case of either being able to protect rural heritage assets from development pressure (through the tight maintenance of green belt designation) or relieving pressure on urban heritage by removing the green belt designation? Or could there be a third way?

Seven point one per cent of London’s green belt is golf courses. This is nearly 2,500 hectares of land, or double the size of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Many other thousands of hectares are wasteland, or land of very poor environmental quality and low biodiversity, some of which contains acres of derelict housing and/or defunct agricultural buildings. This land, although of little use, no beauty and limited or no recreational value (since it is largely privately owned), is overlooked for development simply because it falls within the green-belt designation. Often there is no sensible assessment of the development potential of a site. It is simply deemed as unsuitable for development because of where it is.

In these days, when the assessment of significance forms a key part of decisions regarding development in and around the historic environment, it would seem sensible that this same balancing exercise, this question of significance, be applied to other designations, such as green belt. If it is a choice between building horizontally on poor, low-value, publicly inaccessible, insignificant wasteland in the green belt, or building at high density, vertically within a historic town centre and dwarfing or crowding significant heritage assets, which would we prefer? It is possible that, when viewed in this new way, assessing significance on a site-by-site basis, the loss of some green belt would be preferable.

As ever, moderation and common sense are the key to resolving this issue. As heritage practitioners we need to consider what is happening in our historic urban environments and assess whether the level of pressure to build, in these necessarily limited areas, is acceptable. Should we not be questioning the blind, blanket protection of often insignificant land over the need to protect highly significant urban heritage? In short, should we not be at the forefront of the green belt question on heritage grounds

References [1] Tom Papworth (2015) ‘Loosen the green belt and solve the housing crisis’, http://www.conservativehome.com, 14 January 2016.

This article originally appeared in IHBC's Context 146, published in September 2016. It was written by Carole Fry, a director of AHC Consultants, freelance writer and architectural historian.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Conservation.

- IHBC articles.

- The Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Blue belt.

- Edwardian architecture.

- Edwin Lutyens.

- Green belt.

- Green belt planning practice guidance.

- Greenfield land.

- Historic environment.

- Making the Green Belt work for London.

- National planning policy framework.

- Planning Practice Guidance.

- Radial city plan.

- Repurposing the Green Belt in the 21st Century.

- Safeguarding land.

- The future of the green belt.

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

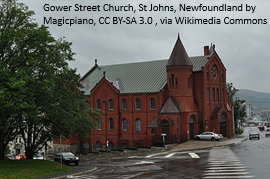

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.