Lighthouse

|

| Lismore lighthouse, built in 1833 by Robert Stevenson. Image by tr_7 from Pixabay. |

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Lighthouses are structures located in or adjacent to navigable waters and are designed to warn passing shipping of the danger from nearby land, reefs and rocky outcrops. During the day, the lighthouse serves as a visual guide for navigation; at night or in poor light, it reveals its position by a flashing beacon located at the top of the structure. Conventional lighthouses are typically tall, slender tower structures, usually circular in plan and tapering towards the beacon at the top. The light from a modern lighthouse can be seen up to 17 miles away.

Due to advances in communications technology in the early part of the 21st century, modern lighthouses may feature an array of signalling equipment, including radio and radar beacons, and sound fog signals (for obscured weather). Lighthouses with such radio aids can also serve as guidance to aircraft and can also be located inland.

[edit] History

One of the earliest lighthouses was the Pharos of Alexandria, Egypt, completed in 247 BC but thought to have been destroyed by an earthquake around 1350 AD. It has been considered one of the wonders of the ancient world. The Romans also built lighthouses, such as those on either side of the English Channel at Dover and Boulogne. The lighthouse was taken to a high art in the 19th century, particularly in the UK which saw many examples built, such as:

- Eddystone, Plymouth (1882), built of granite, height 40m (see below).

- Lismore, Scotland (1833), freestone/limewashed rubble, height 26m.

- Bishop Rock, Scilly Isles, (1858-1887), granite, height 44m.

One of the pioneering examples was by John Smeaton, a civil engineer who in 1759 completed the remodelling of Winstanley’s lighthouse on the Eddystone rocks in the English Channel. Smeaton used hydraulic lime as mortar between granite blocks secured with dovetail joints and marble dowels. Together with the tapered profile, the result was a very stable structure which effectively dissipated wind forces and was to become the prototype for the modern lighthouse, influencing many future engineers.

Robert Louis Stevenson's family constructed a large number of lighthouses, in particular around the coast of Scotland, many in very exposed and inaccessible locations.

[edit] Materials

Masonry has been the predominant building material due to its weight and resistance to weathering, particularly against aggressive coastal environments comprising sea action, ice thrust and wind overturn. Other materials can include concrete, brick, cast iron and steel. Lanterns and fixtures were often made of bronze due to its resistance to corrosion.

Lismore, Scotland (pictured) is a typical 19th century-style lighthouse, with a diameter of 5.8m at the base and walls of 1.4m minimum wall thickness. The masonry is coursed lime-washed rubble, with painted dressings of freestone; the stone is said to have been quarried at Loch Aline nearby. The parapet-walk runs around the light room which is a cast iron superstructure pierced by two rows of square glass panes.

[edit] Light

In ancient lighthouses, beacons were created by wood fires burnt in braziers. Coal was used for this purpose up to the end of the 18th century after which animal or vegetable oils were burnt in lamps. At one point, batteries of candles were used, such as in Smeaton’s light. After around 1850, mineral oil was burned in a series of wicks. Around the end of the 19th century, a further advance, involved burners vaporising mineral oil on a mantle, producing an extremely high brilliance light. This would more often than not be channelled through a lens, such as of the Fresnel type, to focus the light. However, the most significant advance was the introduction of high-intensity electric incandescent lamps: these are clean, safe, adaptable, allow accurate focusing of the optical apparatus and provide a readily-varied concentration of candlepower.

[edit] Construction

Lighthouses can be constructed as fixed structures on land or sea.

The latter can be problematic to construct given the cost and specialist construction techniques required to withstand tides, currents, sea action, ice and the potential for bottom erosion. Offshore stations anchored to the sea bottom are expensive to build and operate. More popular in the US, these are typically steel structures, similar to oil rigs but much smaller, and comprise living quarters, a helicopter deck, machinery area and a tall mast carrying the shipping light, a radio beacon antenna and a warning light for aviation.

When a fixed structure is impracticable, floating buoys (with lights around 7m above the water line) can be used as small warning elements; on a larger scale, lightships (with lights on mastheads) can be permanently moored at the required locations.

[edit] Manual v automated

Throughout history, lighthouses have usually required lighthouse keepers to maintain the beacon and ensure it operates at the right time and in the required manner. However, the advent of Global Positioning Systems (GPS) in the latter part of the 20th century and other improvements in maritime safety have, in many cases, seen the decline of the non-automated lighthouse. Today’s beacons are likely to comprise solar panels and batteries powering a single light mounted on a steel-framed tower.

Because of these advances in navigational systems, some lighthouses have been decommissioned entirely.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- A review of Scotland's historic lighthouses.

- Cardiff tidal lagoon.

- Coastal defences.

- Conserving Cornish harbours.

- Dam construction.

- Freestone.

- Hydroelectricity.

- Hydropower.

- Martello tower.

- Matthew Davidson stonemason and civil engineer.

- New architecture of Scotland’s west coast.

- Seashaken Houses: A lighthouse history from Eddystone to Fastnet.

- Thames barrier.

- Three pieces of infrastructure that have saved lives.

- Tidal lagoon power.

- Waterfronts Revisited: European ports in a historic and global perspective.

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

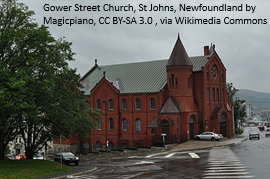

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.