Heritage and Brexit

If we hold a liberal vision of a future society, and thus of heritage, we need to better acknowledge and challenge the various realms and interpretations of heritage that exist.

|

| Colston Hall in Bristol, pictured in the Illustrated London News in 1873. After much controversy, it has been agreed that the building will be renamed when it reopens in 2020 following refurbishment. Edward Colston (1636–1721), a Bristol-born merchant and philanthropist who made much of his wealth from the slave trade, is commemorated in several Bristol streets and buildings. |

‘Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past’ – George Orwell, 1984

Brexit means Brexit. Whatever this actually comes to mean, it is the inescapable phenomenon of our time, evoking anxiety, joy or even indifference; but nevertheless inescapable. Equally, it seems clear that the momentous decision to leave the European Union is part of a wider crisis in the institutions of liberal, metropolitan politics, evident in elections across the west; at the time of writing, most recently in Sweden, that bastion of social democracy.

It can, however, be difficult to know how Brexit relates to our working lives. How does Brexit relate to what we do? The Heritage Alliance has made the case for the direct impact on the heritage sector. [1] It is also important to discuss the wider cultural implications of Brexit. [2] We wish to make a deeper speculation that Brexit is a primarily cultural phenomenon, bound up with issues of individual and group identity and, as such, inextricably linked to our relationship with the past or, in other words, our heritage.

The vote highlights deep cultural schisms within the UK that are, at least to a certain extent, rooted in very different imaginaries of the past and their uses in the present. If people want ‘their country back’, which country is that? Brexit is therefore very much a heritage project that also has implications for what heritage is and does in a post-Brexit country. As Joe Flatman [3] states, ‘some people seek to see Historic England reinforce established cultural orthodoxies; others for it to actively challenge these.’

The rise of heritage is closely linked with the development of the modern nation state; heritage was part of the apparatus of defining national identity and is an integral part of what Benedict Anderson termed ‘imagined communities’. [4] The overt use of heritage in nation-building and nation-destruction has continued on the global stage through to modern times. [5] Yet over time the heritage project has acquired a range of other roles. Specifically, in recent decades two large wider social, economic and political forces have come into play in the practice of heritage. These include but far transcend an impact on heritage, which for shorthand we have called ‘liberalism’ and ‘neo-liberalism’.

While the drive for these arises from very different social constituencies, both have enabled more heterogeneous approaches to heritage to take root. On the one hand there has been a push for defining more pluralist conceptions of heritage and for the heritage sector to make efforts towards a wider social engagement from its historic audiences. We can see this liberal discourse today through, for example, active campaigns to rename British places associated with figures prominent in the slavery trade. It has been agreed that Colston Hall in Bristol be renamed following a programme of refurbishment for this reason. At heart, such liberalism in the hands of policy-makers remains a nation-building agenda; but it seeks to create new and more diverse definitions of national identity.

On the other hand, neo-liberal approaches have assumed dominance across much of Europe despite (indeed, reinforced by) the global financial crisis and austerity. This has had significant direct and indirect consequences for heritage management processes. Directly, there has been an increasing emphasis on the commodification of heritage; we increasingly present heritage as a successful economic good rather than protect it as a cultural good.

Indirectly these processes have been accelerated in recent years by an understandable desperation in many localities to capture any possible economic activity and, as a consequence of austerity, a diminished capacity from the local state to manage change in the historic environment. These philosophies, liberalism and neo-liberalism, are often in competition with each other. However, they can both be characterised as outward-facing, cosmopolitan projects. In their very different ways they break from traditional conceptions of cultural worth and national identity and use heritage, on the one hand, as political critique of traditional nationalism and, on the other, as a globalised economic commodity.

Such cosmopolitanism seems to have been one of the factors in the Brexit vote. David Goodhart [6] suggests that the British population can be divided between ‘somewheres’ and ‘anywheres’; between the well-educated and cosmopolitan metropolitan elite (the anywheres) and an older, more provincial population (the somewhere) who feel out of step with social change and feel an angry resentment that was articulated in the Brexit vote. If both social conservatism and the consequences of globalism are drivers of Brexit, there is a potential tension between the values of the somewheres, who might perhaps be thought to relate more to traditional signifiers of heritage, and the reformulations of heritage suggested by liberalism and neo-liberalism.

If the UK is a divided nation, can it have a united heritage? Indeed, in referring to the UK we have largely been addressing England and, as we know, Scotland and Northern Ireland voted against Brexit. The pasts told in England, and which seem to underpin Brexit, are generally supremacist and exceptionalist in nature, in a way that they are perhaps not so clearly in the other nations, where there are parallel narratives of being colonised by England or, in the case Northern Ireland, where consideration of the past is inextricably bound up with sectarianism. At its most anodyne, heritage can be presented as ‘a reassuringly warm and cuddly blanket by those seeking to sell heritage and those presenting a liberal affirming vision of heritage alike. This ignores that heritage often has ugly and regressive sides. Heritage can be used to engender communal identity but equally it can be divisive.

One response to Brexit is to say that we need to push an agenda based around diversity and inclusivity even harder. That if we include more people, more voices, more interpretations in the liberal heritage project, it can be used to build a more unified sense of place and nation. But efforts to do this thus far have been, at best, only partly successful. In practice the ideas of heritage we carry with us differ enormously between social groups and, indeed, individuals.

What heritage is and what it is does are contested. Rootedness and identity can be conservative, progressive, liberal, neo-liberal and more. But if we hold (as we do) a liberal vision of a future society, and thus of heritage, we need to better acknowledge and challenge the various realms and interpretations of heritage that exist.

References

- [1] Briefings can be found on http://www.heritagealliance.org.uk. Issues identified include funding, regulations and freedom of movement.

- [2] This article links to workshops and interviews we have undertaken with people in the heritage sector. See https://heritagevalue.wordpress.com

- [3] Flatman, J (2017). ‘Identity, Value and Protection: the role of statutory heritage regimes in post-Brexit England’, The Historic Environment: policy and practice 8(3).

- [4] Anderson, B (1983). Imagined Communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism, Verso, London.

- [5] See, for example, Bevan, R (2006). The Destruction of Memory: architecture at war, Reaktion Books

- [6] Goodhart, D (2017) The Road to Somewhere: the populist revolt and the future of politics, Oxford University Press. While Goodhart’s focus is on ‘somewheres’ and ‘anywheres’, he does also have a category of ‘inbetweeners’.

- [7] Ashworth, G J (2006) Editorial: ‘On Icons and ICONS’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 12(5).

This article originally appeared as ‘Before and after Brexit’ in IHBC's Context 157 (Page 14), published in November 2018. It was written by John Pendlebury and Loes Veldpaus from the Global Urban Research Unit at Newcastle University’s school of architecture, planning and landscape.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Brexit.

- Brexit and UK research into cultural heritage.

- Can the heritage of Europe help to integrate the UK.

- Conservation.

- Conservation in Germany.

- Conserving Europeanness.

- DCMS Culture Secretary comments on HM Government position on contested heritage.

- Great Yarmouth Preservation Trust.

- Harmonising heritage in the Nordic countries.

- Heritage.

- Heritage asset.

- Historic building.

- IHBC articles.

- International heritage.

- The Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- World heritage site.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

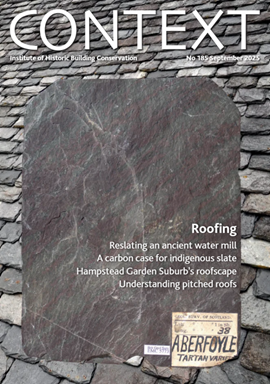

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

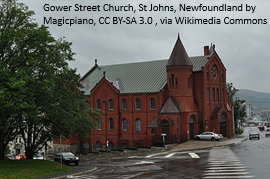

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

Comments