General Hugh Debbieg military engineer and surveyor

This article is part of ICE's Engineer biographies series.

DEBBIEG, Hugh, General (1731-1810), military engineer and surveyor.

No career covering sixty years and rising from Matross (Assistant Gunner) (1742) to General (1803) can be considered anything but successful, but Hugh Debbieg's might have been more so were it not for a series of acrimonious disputes with the Duke of Richmond, Master General of Ordnance, leading to two court martials, in 1784 and 1787, and a premature and enforced transfer to the Corps of Invalids (1799).

During his lengthy career, Debbieg worked on a variety of civil engineering projects, albeit generally from a military perspective. Debbieg began a cadetship at the Royal Military Academy in 1744; his precocious talents being rewarded with a 'work experience' place on what proved a disastrous expedition to Lorient.

In 1746, he returned thence with considerable personal credit to continue his studies in engineering and drawing and in 1748 was sent to work with William Roy (q.v.) on the survey of Scotland where he eventually organised and conducted one of six survey parties, covering parts of Peebles, Lothian and Lanark as far south as the Edinburgh-Glasgow line.

Most of the next decade was spent working on roads where he surveyed an almost continuous route from Newcastle through to Stranraer, although it is unlikely it was ever planned as a single line. The first section—the military road from Newcastle to Carlisle—on which he worked, with Dougal Campbell (q.v.) from 1748 to 1749, was a retrospective solution to General Wade's (q.v.) inability to move his army across country to counter the Jacobite threat in 1745. The second section from Sark Bridge near Gretna Green to Port Patrick (1757) was a forward looking attempt to speed the progress of troops to Ireland. The sections differed in construction—the Newcastle-Carlisle being an entirely new road whereas the Dumfries-shire route improved existing roads wherever possible, although an estimate exists of 'the bridges found necessary to be built on a survey by Captain William Rickson, Deputy Quartermaster General for North Britain and Hugh Dibbieg [sic], Lieutenant of Engineers' (£629 18s Id for twenty-one bridges). The road was actually constructed by Rickson in 1763-1764.

By then, Debbieg had returned to active military service in north America under General Wolfe as his Assistant Quartermaster General, at Louisberg, where he was in charge of four hundred miners, and at Quebec where he was almost the only officer portrayed in West's painting of 'the death of Wolfe' whose presence can be historically proven.

In 1762, Debbieg produced a plan of the town and harbour of St. John's, Newfoundland, with plans for new defences built of masonry costing £72,000. This proved too expensive for the Ordnance Board who finally, ten years later, agreed to his revised scheme built of earth and sods at a saving of £7,000.

In 1763, he produced surveys of Grace and Carboniere Harbours in Conception Bay. During his time in Newfoundland he received 50s a day reduced to 40s 'secret mission' allowance when in 1767 he was sent to France and Spain to survey harbours. He returned with detailed plans of Barcelona, Cartagena, Cadiz and Corunna written up as 'remarks and observations on several seaports in France and during a journey in those countries from 1767-1768'. He not only observed military activities, but the state of roads, noting that the Spaniards were building three new roads in the Pyrenees to bring iron and timber down to the port of Corunna. The book was presented to George III who rewarded him with a pension of Is a day for life.

From 1777 to 1784, Debbieg was Chief Engineer on the staff of the Commander-in-Chief Lord Amherst in charge of all military operations in England including field works, bridges and surveys. He was placed in charge of the defence of public buildings in London during the Gordon riots of 1780. This included the Bank of England who asked him to determine necessary measures for a permanent defence. He remarked that 'I cannot make it a fortress but (can procure) it a greater degree of security than has been done by the frippery designs of a civil jobbing architect'. His estimate was £30,000.

In 1778, he was also Chief Engineer at Chatham at an extra salary of 25s per day where he improved and extended the earth ditch and rampart defences of J. P. Desmaretz (q.v.) (with whom he had worked there in 1755-1756) with massive brick walls coped on the high ground with stone and an underground tunnel system. Work at Chatham included a road from Rochester to Chatham with a three arched span brickwork bridge crossing Rome Lane begun in 1781 (demolished in 1902). The finished road was handed over to the Commissioners of the Rochester Trust in 1783.

This was his only fixed bridge, but in 1779 he had constructed the 'favourite work of mine', a bridge between Tilbury and Gravesend comprising barges supporting a platform running the entire length, arranged to allow passage of ships. Its demolition by Richmond was one of the causes of their acrimony although 'I have the comfort of knowing that in the judgement of many it was deemed a masterpiece'.

He also designed a new, more portable, pontoon for bridging small rivers and tidal inlets. It weighed 3 cwt and was 3 ft. broad and 16 ft. long. This continued in service until 1815 when it was replaced by a design of Charles Pasley (q.v.). While at Chatham he also built a new hospital, and wrote to Lord Sandwich proposing the closure of Gillingham Creek both for the land reclamation of St. Mary's Isle and to improve the navigation of the Medway. As usual Debbieg was ahead of his time the Admiralty finally closing the creek in 1863. As a corollary to this Debbieg also presciently considered that Chatham should be developed solely as a dockyard the current state of the Medway rendering it useless as a harbour.

His professional troubles began in 1782 when the Duke of Richmond became Master General of Ordnance and introduced a series of changes which Debbieg saw as a personal affront, viz. restricting his services to the Commander-in-Chief, removing officers from his command and reducing his pay from 25s to 17s a day. This was even further reduced to 9s with Richmond's reorganisation of the Royal Engineers 'the death warrant of the Corps'.

Debbieg's area of activity was reduced from virtually the whole of the south east to Chatham itself which he considered was being starved of funds to finance Richmond's vastly expensive plans for fortifying Portsmouth and Plymouth. Consequently in 1784 he wrote the Duke a letter accusing him of partiality, offering him slights and oppressing and humiliating him by his reforms, his changes and his crudities. This led to his arrest and court martial, but a court full of generals who had requested his services in the past merely reprimanded him and wrote a minimalist apology for him to utter in court.

Unsurprisingly matters did not improve. In 1785, Richmond refused him the position on the Board of Land and Sea Defences recommended by Parliament. In 1789, Debbieg once again put pen to paper this time describing the Duke's plans as 'a system only calculated to invite the enemy into the very bosom of Britain'. For good measure he published a copy in the Gazette. This time he was suspended for six months and despite the sympathy of both the King, who after his retirement granted him an extra 12s per day pension, and political satirists (see the Rolliad) it was effectively the end of his career.

Despite subsequent promotion to General he was virtually unemployed for the last twenty years of his life. Debbieg married Janet Seton in Edinburgh in 1763, Janet was the daughter of Sir Henry Seton, the 3rd Baronet of Abercorn, Janet died in 1801. They had three sons: Clement, Henry and Hugh, the last two christened at Swallow Street Scottish Church, Westminster, in 1767 and 1769 respectively. Henry subsequently became a Lieutenant-Colonel, and Fort Major at Dartmouth Castle. Clement was also in the Army, whilst the third son Hugh was an Exchequer clerk in Whitehall originally under William Pitt the Younger.

Debbieg died at Margaret Street, Cavendish Square, London, on 27 May 1810.

Works:

- 1762-1770. Defences for St. John's Harbour, Newfoundland, £65,000

- 1778-1789. Great Lines, Chatham, Brompton, Fort Amherst, c. £45,000; £27,000 spent, 1778-1780

- 1779. Temporary military bridge across the Thames between Tilbury and Gravesend

- 1781-1783. Road from Rochester to Chatham (including three-span brick arch bridge)

Written by SUSAN HOTS

This text is an extract from A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland, published by ICE in 2002. Beginning with what little is known of the lives of engineers such as John Trew who practised in the Tudor period, the background, training and achievements of engineers over the following 250 years are described by specialist authors, many of whom have spent a lifetime researching the history of civil engineering.

Featured articles and news

A threat to the creativity that makes London special.

How can digital twins boost profitability within construction?

A brief description of a smart construction dashboard, collecting as-built data, as a s site changes forming an accurate digital twin.

Unlocking surplus public defence land and more to speed up the delivery of housing.

The Planning and Infrastructure bill oulined

With reactions from IHBC and others on its potential impacts.

Farnborough College Unveils its Half-house for Sustainable Construction Training.

Spring Statement 2025 with reactions from industry

Confirming previously announced funding, and welfare changes amid adjusted growth forecast.

Scottish Government responds to Grenfell report

As fund for unsafe cladding assessments is launched.

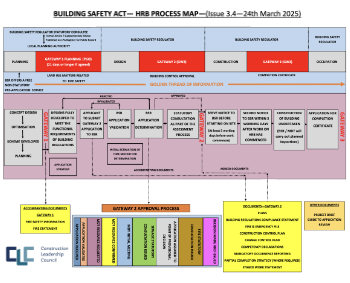

CLC and BSR process map for HRB approvals

One of the initial outputs of their weekly BSR meetings.

Architects Academy at an insulation manufacturing facility

Programme of technical engagement for aspiring designers.

Building Safety Levy technical consultation response

Details of the planned levy now due in 2026.

Great British Energy install solar on school and NHS sites

200 schools and 200 NHS sites to get solar systems, as first project of the newly formed government initiative.

600 million for 60,000 more skilled construction workers

Announced by Treasury ahead of the Spring Statement.

The restoration of the novelist’s birthplace in Eastwood.

Life Critical Fire Safety External Wall System LCFS EWS

Breaking down what is meant by this now often used term.

PAC report on the Remediation of Dangerous Cladding

Recommendations on workforce, transparency, support, insurance, funding, fraud and mismanagement.

New towns, expanded settlements and housing delivery

Modular inquiry asks if new towns and expanded settlements are an effective means of delivering housing.