Non-discriminatory building design

This article needs more work. To help develop this article, click 'Edit this article' above.

Contents |

[edit] Background

Over the last two to three decades there has been great progress in making the built environment (buildings, streets and transportation) more accessible, especially for people with disabilities and access problems. This is reflected in the introduction of Acts, codes, standards and regulations such as the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA 1995) and it’s successor the Equality Act (2010). For buildings, more specific requirements are stipulated in the Building Regulations Part M (2004, amended 2013) and in British Standards. NB See Access and inclusion in the built environment: policy and guidance for more information.

[edit] Experiential discrimination

Experiential discrimination occurs when not all users get to enjoy the same experience of a building or building feature. For example, there should be one entrance that serves, rather than a “special” entrance for wheelchair users. Such discrimination should designed-out when consideration is made of people's different strengths and weaknesses in physical, sensory and cognitive areas (including phobias).

An example of experiential discrimination is when a building has a central area that is served by escalators. Those who do not wish to use, or cannot safely use, the escalators require a lift. The lift should have a window so that those who use it are not denied the experience of appreciating the space (and also to support those with claustrophobia). A further, enclosed lift would support those who have agoraphobia (fear of open spaces, or those spaces perceived as hard to escape from). Passengers would thus be given a choice of lift type to better serve their preferences.

For those who find long distances a barrier, good design would provide seating at intervals to allow rest and recovery. This is of particular importance on staircases where seats half way up a staircase can enable people to rest with dignity. A flip-down seat in a lift can offer respite in crowded lifts, or if lift journey times are long.

The built environment is predominantly designed for right-handed users (in terms of door openings, light switch locations, etc.), however, studies have shown that between 10 and 30% of the population is left-handed. Additionally, people who have strokes are often affected on the left-hand side of the brain, which affects the right-hand side of the body.

Signage can also be misinterpreted. The international sign for disability is the white wheelchair symbol on a blue background. This is not meant to be a “for wheelchair users” sign but is often interpreted as such. A pregnant lady, for example, may see the symbol on a lift and decide that they should not use it (self-discrimination) and hence struggle on a staircase with shopping and the unnecessary risk of tripping/ falling.

[edit] Conclusion

Designers, and others who bring designs into realisation, do not deliberately discriminate against users or persons with particular disability, however there is inherent discrimination in the buildings that we create. It is hoped that future generations of designers will become more empathetic to the needs of a wider range of users and therefore help create built environments that can be used and enjoyed by a wide spectrum of users in a natural, unforced, way.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Access consultant.

- Access and inclusion in the built environment: policy and guidance.

- Changing lifestyles.

- Inclusive design.

- Lifting platform.

- Stairlift.

- The London Plan.

- Wheelchair platform stairlifts.

[edit] External references

- The Lifetime Homes.

- Supplementary Planning Guidance in relation to the Olympic Legacy.

- Supplementary Planning Guidance: Planning for Equality and Diversity in London (2007).

- Supplementary Planning Guidance: Achieving an Inclusive Environment (2004).

- The Equality Act 2010.

- Part M of Building Regulations.

- Approved Document M.

- The Principles of Inclusive Design.

- ODA Inclusive Design Standards (2008).

Featured articles and news

A threat to the creativity that makes London special.

How can digital twins boost profitability within construction?

A brief description of a smart construction dashboard, collecting as-built data, as a s site changes forming an accurate digital twin.

Unlocking surplus public defence land and more to speed up the delivery of housing.

The Planning and Infrastructure bill oulined

With reactions from IHBC and others on its potential impacts.

Farnborough College Unveils its Half-house for Sustainable Construction Training.

Spring Statement 2025 with reactions from industry

Confirming previously announced funding, and welfare changes amid adjusted growth forecast.

Scottish Government responds to Grenfell report

As fund for unsafe cladding assessments is launched.

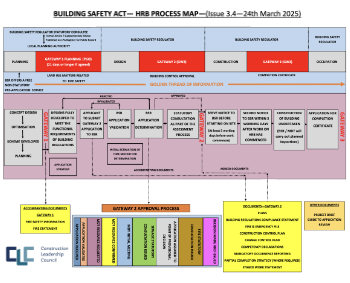

CLC and BSR process map for HRB approvals

One of the initial outputs of their weekly BSR meetings.

Architects Academy at an insulation manufacturing facility

Programme of technical engagement for aspiring designers.

Building Safety Levy technical consultation response

Details of the planned levy now due in 2026.

Great British Energy install solar on school and NHS sites

200 schools and 200 NHS sites to get solar systems, as first project of the newly formed government initiative.

600 million for 60,000 more skilled construction workers

Announced by Treasury ahead of the Spring Statement.

The restoration of the novelist’s birthplace in Eastwood.

Life Critical Fire Safety External Wall System LCFS EWS

Breaking down what is meant by this now often used term.

PAC report on the Remediation of Dangerous Cladding

Recommendations on workforce, transparency, support, insurance, funding, fraud and mismanagement.

New towns, expanded settlements and housing delivery

Modular inquiry asks if new towns and expanded settlements are an effective means of delivering housing.