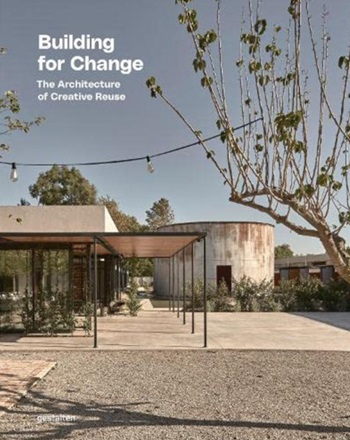

Building for Change: the architecture of creative reuse

Building for Change: the architecture of creative reuse, Edited by Robert Klanten, Rosie Flanagan and Andrea Servers, Gestalten, 2022, 253pp, lavishly illustrated with colour photographs, many full-page.

Building for Change is a heavyweight proponent for the creative reuse of buildings, in its physical size and, more importantly, its demonstrative power of examples and logic. It is not focused specifically on the reuse of buildings which would be conventionally classed as heritage assets and which could have been demolished, although it does include a few examples of the successful adaptive reuse of ‘historic buildings’.

It is not, therefore, aimed specifically at heritage professionals. Rather, it makes a powerful case for minimising the waste of materials, energy, space and opportunities by taking advantage of those attributes which are already embodied in existing buildings. It is aimed at every professional and all who are interested in working with the world’s existing building stock.

The book advocates reuse of existing buildings as the default methodology for architecture and development, citing it as a working ethos rather than a passing style. It argues that inventively re-purposing existing buildings demands greater creative thinking than working with a blank canvas. As most of the structures involved are not heritage structures and not ‘constrained by conservation policy’, the recommended approach not only allows for variable ‘dismantling’ of fabric but also requires reassessment of practice, procurement and indeed expectations of practitioners and owners/developers. (Unfortunately, the latter can be hard to find.)

The case for the architecture of creative reuse is persuasively made in simple language in a range of short essays on different aspects of reuse, which are spread throughout the book, interspersed between 35 world-wide case studies. Most are in Europe, some are in Asia and a few in Africa, with just three from the UK, although Heatherwick Studio’s conversion of a grain silo in Cape Town into an art gallery and hotel is included. Most are in urban settings, with a couple of rural barn conversions, pleasingly with alternative solutions (a hotel and library in China and offices in Spain) to the almost ubiquitous residential conversions encountered in the UK.

The case studies kick off with a former steel factory in Shanghai, where the external steel framework, pipes and conduits have been left in place, with a new structurally independent polycarbonate insertion which is now used as an exhibition centre and offices. The whole is an eye-catching gateway to an eco-industrial park. The conversion of concrete grain silos in Cape Town and Basel required major interventions in the fabric but are reminders of lost opportunities for similar long-gone silos on the banks of the River Mersey and elsewhere.

In some cases, the patination of the original fabric has been retained as a reminder of the building’s past and in recognition of the beauty of the natural order of decay (the wabi sabi concept of Japanese culture). In others the buildings are totally transformed with new surfaces, features and additions.

My favourite example is the former government centre in Hong Kong, which is an historic building (built 1841). It has been converted into an arts centre but its heritage status has not prevented exciting new buildings within the ensemble which overtly express the spirit of the day. The setting of these low-rise old and new buildings has been swamped by the high-rise structures all around them but, perversely, this serves to emphasise their importance and appeal.

As the IHBC is the institute of heritage professionals, we have a general duty to prevent the unnecessary demolition of buildings which have heritage value and so should learn from what has been achieved in the reuse of any buildings. Regrettably, the demolition of historic buildings is occasionally authorised, despite the best efforts to save them. The tragic clearance of the north side of Lime Street in Liverpool, including the Futurist Cinema, was authorised a few years ago after much objection, only to be replaced by a cartoon depiction of the building that was removed. On the flip side, there are recent and current cases where the reconstruction of protected buildings, which have been illegally demolished, has been rightly enforced. One can only hope that these cases provide a deterrent for any future unauthorised losses. Similarly, the proposed demolition of the Marks and Spencer Building in Oxford Street has stirred a public outcry and a stay of execution.

Crucially there is now a growing realisation that almost all buildings, whether decaying or ‘ugly’ have some value, not least in the embodied energy, which was employed in their original construction and their materials, but, equally, in their potential for reuse. Even back in 2007, Dennis Rodwell trumpeted the obvious symbiotic relationship between conservation and sustainability in his Conservation and Sustainability in Historic Cities.

Rodwell wrote: ‘It is reported that the UK construction industry accounts each year for the use of six tonnes of building materials per head of population and 35 per cent of the total of all wastes. It also accounts for the manufacture of 3.5 billion bricks [and] the destruction of 2.5 billion. “It doesn’t,’ as one commentator has written, “take a genius to work out the absurdity of such an equation.”’

The ultimate objective of Building for Change is that the architecture of creative reuse helps to build a better tomorrow.

This article originally appeared as ‘Reuse by default’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 178, published in December 2023. It was written by John Hinchliffe, independent heritage consultant at Hinchliffe Heritage.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings

- 100 Sustainable Scottish Buildings.

- Conservation.

- Heritage.

- Historic environment.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- Planning for sustainable historic places.

- Reconciling conservation and sustainable development.

- Sustainability and Conservation of the Historic Built Environment - an IHBC Position Statement.

World Heritage and Sustainable Development: new directions in world heritage development.

IHBC NewsBlog

IHBC Context 183 Wellbeing and Heritage published

The issue explores issues at the intersection of heritage and wellbeing.

SAVE celebrates 50 years of campaigning 1975-2025

SAVE Britain’s Heritage has announced events across the country to celebrate bringing new life to remarkable buildings.

IHBC Annual School 2025 - Shrewsbury 12-14 June

Themed Heritage in Context – Value: Plan: Change, join in-person or online.

200th Anniversary Celebration of the Modern Railway Planned

The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825.

Competence Framework Launched for Sustainability in the Built Environment

The Construction Industry Council (CIC) and the Edge have jointly published the framework.

Historic England Launches Wellbeing Strategy for Heritage

Whether through visiting, volunteering, learning or creative practice, engaging with heritage can strengthen confidence, resilience, hope and social connections.

National Trust for Canada’s Review of 2024

Great Saves & Worst Losses Highlighted

IHBC's SelfStarter Website Undergoes Refresh

New updates and resources for emerging conservation professionals.

‘Behind the Scenes’ podcast on St. Pauls Cathedral Published

Experience the inside track on one of the world’s best known places of worship and visitor attractions.

National Audit Office (NAO) says Government building maintenance backlog is at least £49 billion

The public spending watchdog will need to consider the best way to manage its assets to bring property condition to a satisfactory level.